- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: India: a love story

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Foreign travellers in India face four inevitable questions. ‘What is your good name?’ is usually followed in rapid succession by ‘Where are you coming from?’(meaning from which country), ‘Are you married?’ and, finally, ‘What is your religion?’. Backpacking through India twenty years ago, the first three questions presented few problems. My name was easy, Australia was recognised as a cricket-playing country, and I was young enough for my lack of a wife to be passed over as a matter of only mild embarrassment. The fourth question however, proved tricky. Usually, I gave the technically correct answer that I had been baptised into the Anglican Church – a reply that generally satisfied my interlocutors and not infrequently led into rambling, good-natured discussions about the similarities between the world’s great faiths. Once, I ventured a more honest response. ‘I am an atheist,’ I told a couple of friendly young Indian men on a long train journey. ‘I do not believe in any God.’ Their shock was palpable. It was not so much my spiritual deficit that appalled them as my arrogance. How could anyone have the audacity to declare that God did not exist? Our conversation never recovered. In response to all future interrogations, I retreated to my dissembling line about Christianity. The experience did not shake my disbelief, but it did serve to engender a greater respect for the question. Religion, I belatedly realised, is an important matter.

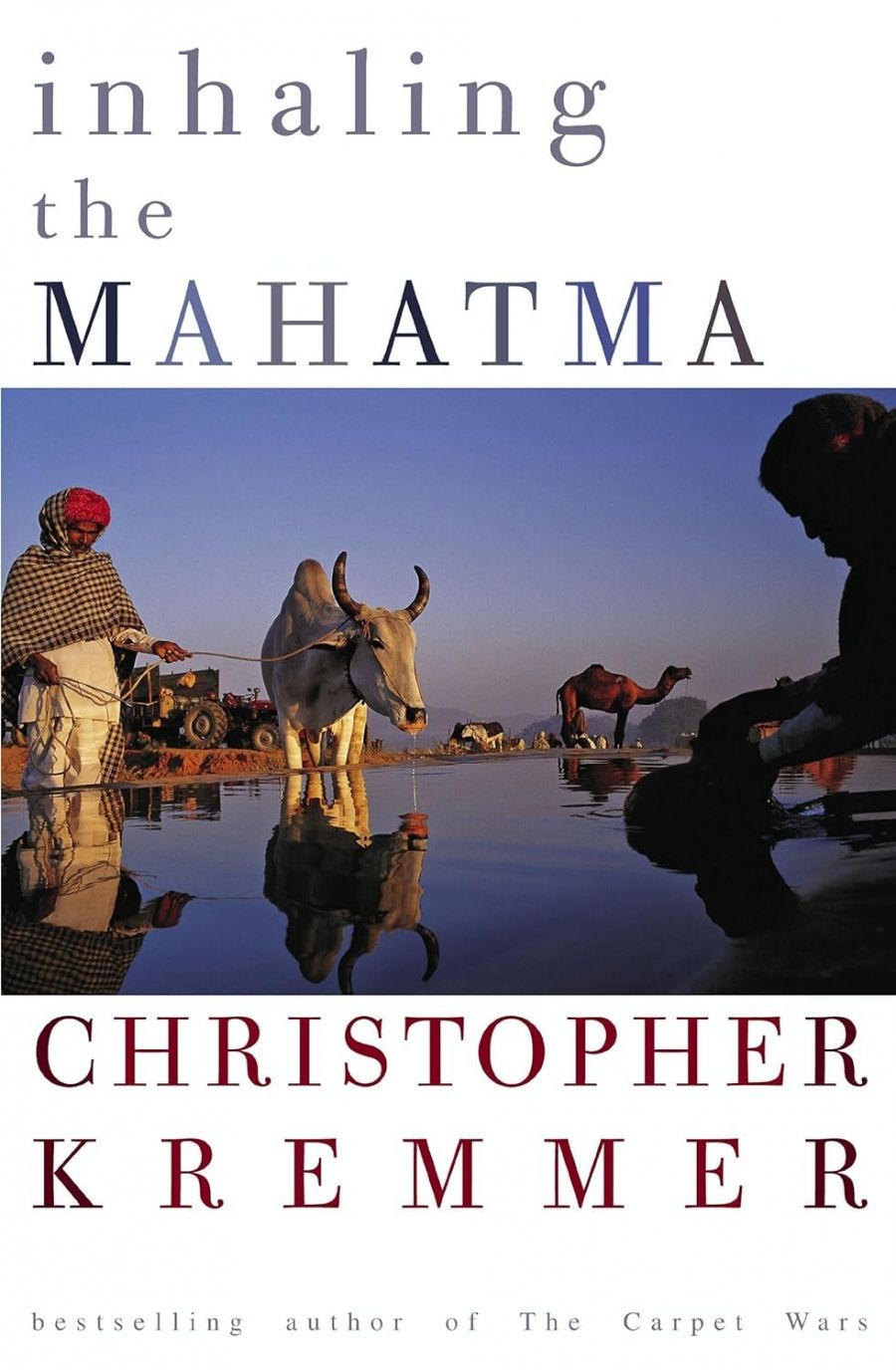

- Book 1 Title: Inhaling the Mahatma

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $35 pb, 440 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Kremmer describes India as ‘contagiously spiritual’, and his own quasi-religious journey or yatra is one of the several narratives that wind through his expansive and immensely enjoyable book. Inhaling the Mahatma, like Kremmer’s previous efforts, The Carpet Wars (2002) and Bamboo Palace (2003), is part travel writing, part political and historical study, part journalism and part personal narrative. It is also a love story, recounting Kremmer’s growing affection for, and engagement with, India, alongside his whirlwind romance with Janaki Bahadur, the woman who becomes his wife.

At this point, I should declare that I know Kremmer quite well, having worked with him for many years at the ABC, so the broad outlines of his personal narrative were familiar to me. The detail was not, and some of it is hilarious. I particularly enjoyed the account of Kremmer and Janaki breaking the news of their engagement to her parents, and of the author’s farcical odyssey through a vast and chaotic New Delhi court complex on their wedding day in search of the judge who is supposed to marry them. The anecdote that gives rise to the title is also amusing, but I won’t spoil the story. Suffice to say that it has a literal, as well as a metaphorical meaning.

The book traverses fifteen tumultuous years in the life of India and encompasses key events of the time, including the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi (whom Kremmer had interviewed at length just weeks before his death), the election of India’s first non-Congress Party government, the 1998 nuclear weapons test (and Pakistan’s tit-for-tat response), communal riots in Bombay, and the burning to death in 1999 of Australian missionary Graham Staines and his two young sons in Orissa. But a single event during Kremmer’s first posting to New Delhi dominates all others, and its repercussions are felt throughout the narrative: the tearing down of the Babri Masjid in the city of Ayodhya, in December 1992. I recall with a searing clarity Kremmer’s chilling radio report from the scene, as he gave an eyewitness account of an army of kar seva (Hindu ‘volunteers’) scaling the mosque and tearing it apart brick by brick. Hindu militants targeted the mosque because they claimed that it was built on the birthplace of the deity Lord Rama. Its destruction was a momentous event, and was followed by days of communal violence in which some 2000 people, mostly Muslims, were killed.

The back story of Kremmer’s report on the destruction of the mosque is one of the many absorbing episodes in this book. As a fellow journalist, I had been somewhat in awe of my well-organised and well-connected colleague. So it was something of a professional relief to read his account of that horrendous day and to learn that Kremmer had more or less stumbled into the midst of the mayhem. Finding himself at the epicentre of the story, he was frightened and distraught, and quickly sought an escape route. The honesty of Kremmer’s writing here is impressive and helps to demystify the often reified role of the journalist and correspondent.

When Kremmer returns to Ayodhya twelve years after the destruction of the mosque, he finds that the place where it once stood has been turned into a site of pilgrimage. Much of the rubble remains where it fell, and devotees queue to pray before a couple of Hindu idols sheltered in a ‘small tented shrine perched atop the ruins of the mosque’. The idols are approached through a series of caged walkways and guarded around the clock by Indian soldiers, at a cost of $1 million a month. The area is swept twice daily for bombs, for fear that it might be targeted by Islamist suicide bombers. The ultimate fate of the site remains unresolved, its future a matter of intense legal and political dispute. India’s history wars are far from over, and Ayodhya remains a crucial battlefield.

Inhaling the Mahatma is not chronological: Kremmer jumps around between the years, usually deftly, and shifts with little effort between the tale of his private life and the grand narratives of the nation. The fall of the Babri Masjid and other landmark political events are interwoven with Kremmer’s journeys around India to illustrate two apparently contradictory but intimately connected historical shifts: the rise of a muscular and militant Hinduism on the one hand, and India’s transformation into an economic powerhouse on the other.

It is one of the great ironies of contemporary India that the emergence of the Bhartiya Janata Party (BJP), a backward-looking religious party that yearns for a mythical era of Hindu purity and greatness, should have coincided with a radical modernisation of the Indian economy and society. In government, the BJP accelerated the dismantling of the quasi-socialist policies of the once-dominant Congress Party, opening up the country’s moribund state-owned industries to competition and foreign investment. The results are neither uniformly good nor uniformly bad, but evidence of progress is irrefutable. As Kremmer points out in his preface, at independence in 1947 only one in five Indians could read or write, and the average life expectancy was just thirty-two. Today, there are many more Indians to be housed and fed – ‘one in every six people on our planet is an Indian’ – yet they can expect to live twice as long and two-thirds of them are literate. Kremmer displays enormous sympathy for the great and ambitious project that is India, the world’s largest democracy. Kremmer attributes India’s transformation to the combination of early nation-building investments in education and health during the Congress era, and the energising influence of capitalism unshackled by more recent governments. Of course, there are still plenty of paupers to be found, and Kremmer is alive to the dilemmas of living amidst poverty. As he writes, ‘it is impossible to be at once moral and comfortable’ in India, since even if you ‘enjoy a modicum of prosperity and security, it means you occupy a privileged place in a monstrous hierarchy’.

This is a crowded and absorbing book, complex and multifaceted, like its subject matter. Some sentences are as busy as an Old Delhi laneway; now and again I would have preferred a little more restraint in the writing. Judicious editing may also have made for a better book overall. Interesting though they are, the chapters on art (‘Virtual Reality’) and the legal system (‘The Temple of Justice’) could have been omitted to sustain the narrative momentum. Detailed knowledge of recent Indian politics is not necessary to enjoy Inhaling the Mahatma, but a passing familiarity helps.

Kremmer’s writing is fluid, his descriptions apposite, his metaphors original. He effortlessly weaves relevant historical detail and appropriate literary references into the text. He is an engaging storyteller with a skill for capturing and rendering conversation. There are fine profiles of key political figures, such as the late Rajiv Gandhi and his up-and-coming son, Rahul, and affectionate portraits of Janaki’s gently squabbling parents and the staff at the family residence in New Delhi’s Civil Lines. Best of all are the remarkable people Kremmer encounters on his journeys, such as the ambitious and outwardly successful call centre worker Deep Singh, who is so stressed that he suffers recurring nightmares; or the unrepentant wannabe militant who hijacked Kremmer’s plane and whom Kremmer searches out and confronts in an interview several years later. My favourite is the Hindu priest-cum-wrestler, Mahant Gyandas, a sadhu (Hindu ascetic) who sheltered Muslim families in his temple when Ayodhya exploded into violence and who nurtures a forlorn dream that one day a mosque and a temple might stand peacefully side by side on the site of the destroyed Babri Masjid.

Comments powered by CComment