- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Lightdark

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

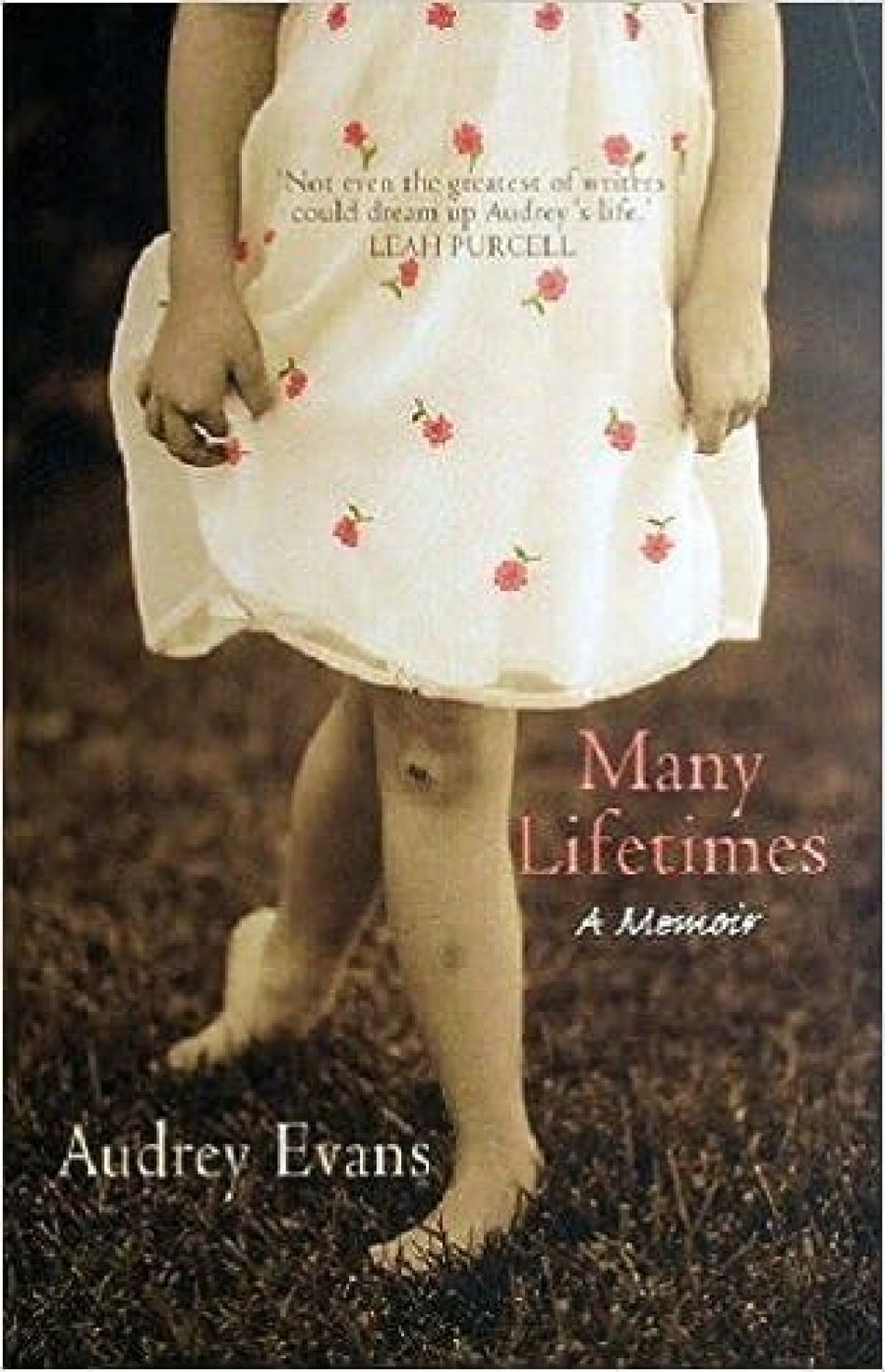

By definition, chiaroscuro is Italian for lightdark; in practice, it is a technique wielded by painters and graphic artists, whereby dynamic applications of highlight and shade are contrasted for dramatic impact. Along with Rembrandt and Caravaggio, Audrey Evans proves herself to be a master of chiaroscuro in her memoir, Many Lifetimes. One can see the hand of the artist as she sketches her truths in simple, yet striking, strokes; Evans writes with a raw honesty that turns a spotlight onto chosen moments in her life, and allows others to remain enveloped in darkness.

- Book 1 Title: Many Lifetimes

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Random House, $32.95 pb, 280 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Evans opens Many Lifetimes with a minimalist description of her life as ‘long and difficult and long and good’. She generously gives us a glimpse of the ‘good’ before plunging us into the dismal depths of the ‘difficult’: the memoir begins, and ends, with a portrait of Evans, aged fifty-nine, graduating from Griffith University. For many students, the graduation ceremony is something of a celebratory chore: a self-conscious parade is led across the stage in a musty auditorium, flashbulbs track every unsteady step taken, while a sea of hands sporting glowing digital cameras waves over creaky seats. For Audrey Evans, however, this ceremony marks the pinnacle of a tumultuous uphill journey toward education and self-identification; her academic success shines like a beacon at the end of a treacherous path.

Born in the 1930s, Evans was raised in poverty, by a father obsessed with keeping his family insulated in darkness. He is depicted as an abusive, alcoholic, yet somehow lovable Irishman, a man overtly ashamed of his Aboriginal wife and their lightdark children. This racial discrimination extends to Evans’s social environment; at school, ‘the blacks, Chinese kids and the dunces’ sat in the front three rows of the classroom, so that the teacher ‘was able to look over the top of us … and pretend we weren’t even there’. Segregation and a pervasive sense of intolerance provide the isolating backdrop to Evans’s youth, and foreshadow the emotional seclusion she is to endure over the next forty years.

Surprisingly, Evans’s account is notably lacking in cynicism. With unbiased, unembellished language, she describes a succession of life-altering events (sexual abuse, teenaged pregnancy, her mother’s death and the subsequent scattering of her family across Queensland, prostitution, strained familial relations, the survival of, and escape from, her abusive first marriage) with the measured eye of a tactician plotting the next move in a battle on unstable terrain. Evans’s writing does not suggest that she suffers from any sense of inadequacy because of these experiences, nor does it offer any plea for sympathy. Instead, one becomes aware that retrospective retelling has awarded Evans with the gift of lucid detachment.

Lucidity is invaluable to one who has endured these hard-ships with depression as her constant, and inescapable, companion. Unable to articulate the source of her sadness, and beset by the alcoholism that accompanied and alleviated it, Evans was frequently institutionalised in various mental hospitals, all of which prescribed ‘shock treatment’ as a cure for ‘insanity’. Evans leaves undescribed the bulk of her time in the mental institutions; instead, facsimiles of official documents from the Goodna Mental Hospital appear as appendices to the memoir. These documents act as harsh counterpoints to Evans’s sparse, subtle prose, and supply details that she has omitted (willingly, or subconsciously) from her narrative.

Ultimately, it is Evans’s unflinching will to survive that makes her story so compelling. She is as steadfast as the horses she lovingly tends during her employment on cattle stations, and moments of darkness are punctuated with evidence of her determination. Her strength of will is captivating, yet she rarely seems aware of it. When describing her reluctance to turn to her siblings for aid or comfort, she remarks: ‘They were no better equipped to survive than I was.’ What an ironic comment, coming from a woman who has endured everything. As Leah Purcell notes in her laudatory foreword: ‘Not even the greatest of writers could dream up Audrey’s life.’ Nor could they speak of it with her un-wavering objectivity.

Many Lifetimes, the fruit of a Masters in Creative Writing at the University of Queensland, confronts readers with a series of unsettling dualities – light/dark, precision/imprecision, memory/forgetting – but the author’s tone is always reassuring, simple and uplifting. Evans assures readers: ‘I know who I am, I say, I have always known.’ Fortunately, now we do too.

Comments powered by CComment