- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: One side of the story

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When is it morally defensible to take one’s own life? Whenever, might be the first response: it is, after all, one’s own life. While the church still regards it as a grave sin, attempted suicide is not a crime, though helping someone else to commit suicide is. Yet does not a desire to end one’s life at a time of one’s own choosing have to be weighed against the pain it might cause others? Is suicide not a statement to family and friends that whatever love, care and support they have given, it was not enough?

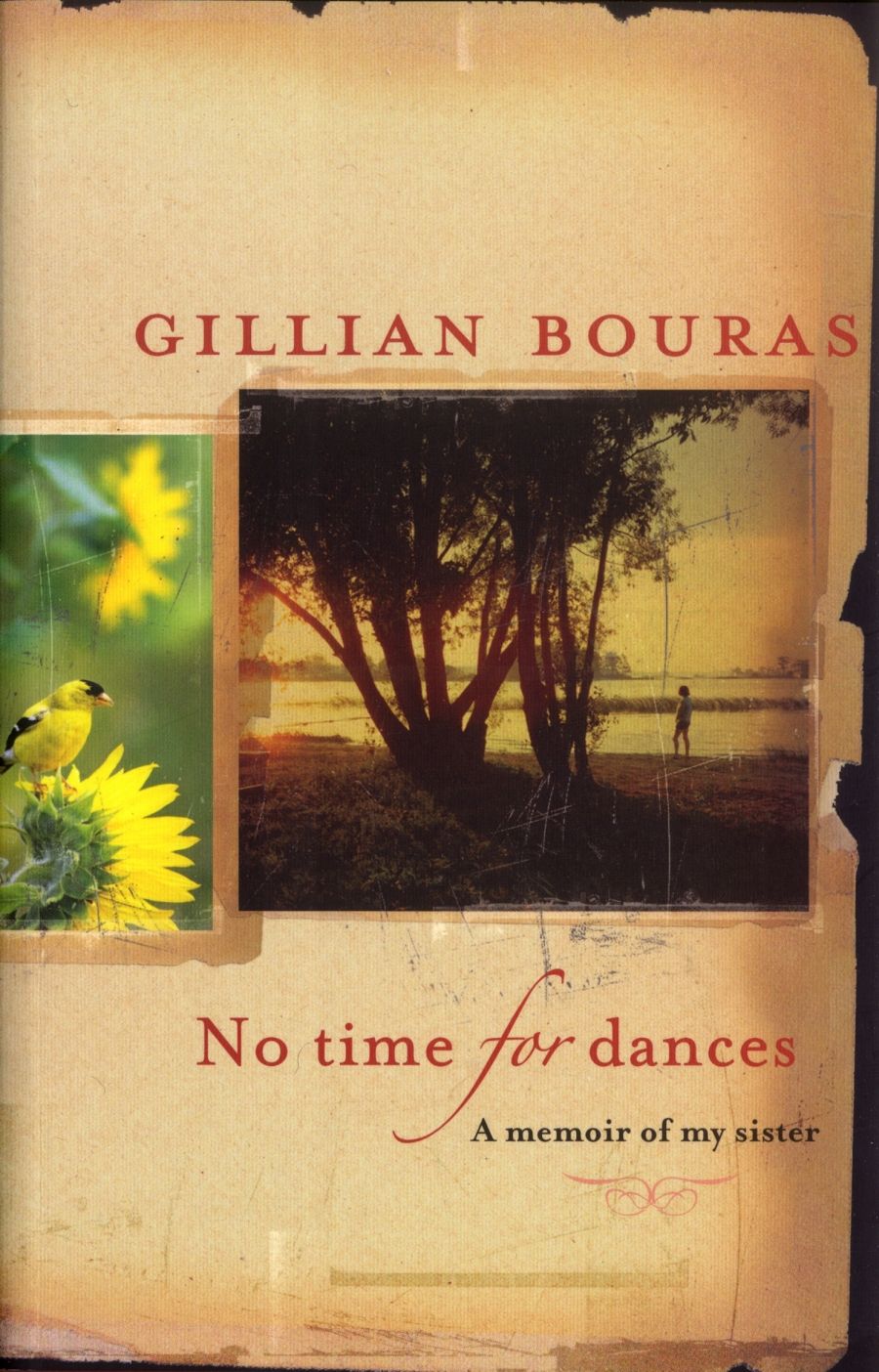

- Book 1 Title: No Time For Dances

- Book 1 Subtitle: A Memoir Of My Sister

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $24.95 pb, 228 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Before writing, Bouras spent much time reading on the subject of suicide. She quotes, briefly, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Albert Camus, as well as the sociologist Emile Durkheim, who believed that ‘the suicide potential would always be high’ in cases where there was ‘excessive mother love, father rejection and inferiority induced by siblings’ (in which case, the wonder must be that suicide is not far more prevalent than it is). I would have wished for more discussion about the philosophical and ethical issues surrounding suicide, but this is perhaps not what the book is intended to be about. It is, after all, subtitled ‘A memoir of my sister’. To a large extent, the book is about Jacqui. Yet one can’t help feeling it is even more about Gillian’s obsession with her sister.

It is an obsession that Bouras admits. They had a close relationship – there were only fifteen months between them – but an intensely competitive and jealous one. There is probably always some jealousy between sisters, but this seems to have been extreme. As children, Gillian and Jacqui often had physical fights, biting, scratching, hair-pulling: ‘the like of which I never saw my three sons engage in. Perhaps this is the primitive nature of girls,’ Bouras writes. (As one of four sisters and as a mother of four daughters, I can tell her it is not.)

Gillian was the cautious, well-behaved one; the good student, the hard worker. Jacqui was ‘a creature of charm, beauty and grace’, who, according to their mother, could have done just as well academically as Gillian if she had wanted to. As Bouras saw it, her mother’s role was to make sure that Gillian did not get big-headed, while bolstering Jacqui’s self-esteem. ‘Jacqui was the beauty and I was the brain,’ she writes bitterly. She still smarts at a comment made by a friend before her wedding, who said that she must be afraid that Jacqui would outshine her.

There is a problem for the reader. However much Bouras emphasises how engaging and beautiful her sister was, and however much she loved her, she also paints her as a self-obsessed and difficult woman. She treated her boyfriends cruelly, to Bouras’s dismay. At family parties, she ‘sat and scintillated and expected to be waited on’. Her behaviour was irrational and selfish. She had ‘no sense of appropriate boundaries’. One has the uncomfortable sense of hearing the story from one side only. Added to this is the knowledge that – and Bouras acknowledges this – her sister is no longer around to defend herself.

Bouras spends much time exploring factors in their upbringing that might have prompted Jacqui to take her life, and working through what to this reader seems her own quite unnecessary guilt. For the crux of the tragedy is that Jacqui was mentally ill. She spent years taking psychiatric drugs, undergoing shock treatment and even a leucotomy (a form of lobotomy), none of which had any lasting benefit. Talking to the psychiatrist who last treated her, Bouras discovered that, shortly before her death, Jacqui had been told there was nothing more he could do for her. Pressed as to what the exact diagnosis had been, the psychiatrist said: ‘Your sister had a severe personality disorder that in my opinion was incurable.’

Bouras found this diagnosis confronting as indeed would any layperson. What does it mean, a personality disorder – a disordered person? Who, as Bouras asks, has a completely ordered personality? The doctor also told Bouras he should have known what was coming, because ‘she was so happy the last time I saw her, and that’s often a sign, you see, that the decision’s been made’. Could it be that Jacqui’s existential pain was such that she had simply made a ra-tional decision to end it? As Marcus Aurelius – quoted by Bouras in the beginning of the book – said in 180 AD: ‘The house is smoky and I quit it. Why do you think that this is any trouble?’

In her earlier books – A Foreign Wife (1986) comes to mind – Bouras has been similarly unafraid of writing about intensely personal matters. ‘This writing is undoubtedly the hardest task I have ever undertaken,’ she says. One can see why. One also hopes that the writing of it helps to assuage some of her anger.

Comments powered by CComment