- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Little Digger to pottering duffer

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Major historical figures generally attract multiple biographies. Napoleon and Nelson have, reputedly, amassed more than 200 biographies each – with successive waves of interest reflecting the constant need for reinterpretation. But at some point we must strike a declining marginal utility as we tally the titles – biography as running soap opera appears a postmodern accoutrement. In Australia, we have not yet managed to produce a biography of each prime minister – then along comes another on the ‘Little Digger’ Billy Hughes (1862–1952), without doubt one of our most colourful political leaders and written-about subjects. If not 200 titles, then there is certainly a small bookshelf full of respectable studies and serious essays on him, not to mention his own books and the many cameo appearances he makes in political memoirs and other works of his generation. So, do we need another interpretation? Indeed, does this ‘short life’ of ‘King Billy’ offer a new interpretation? Why did Aneurin Hughes – his namesake but no relation, and more on that later – commit to this laborious project?

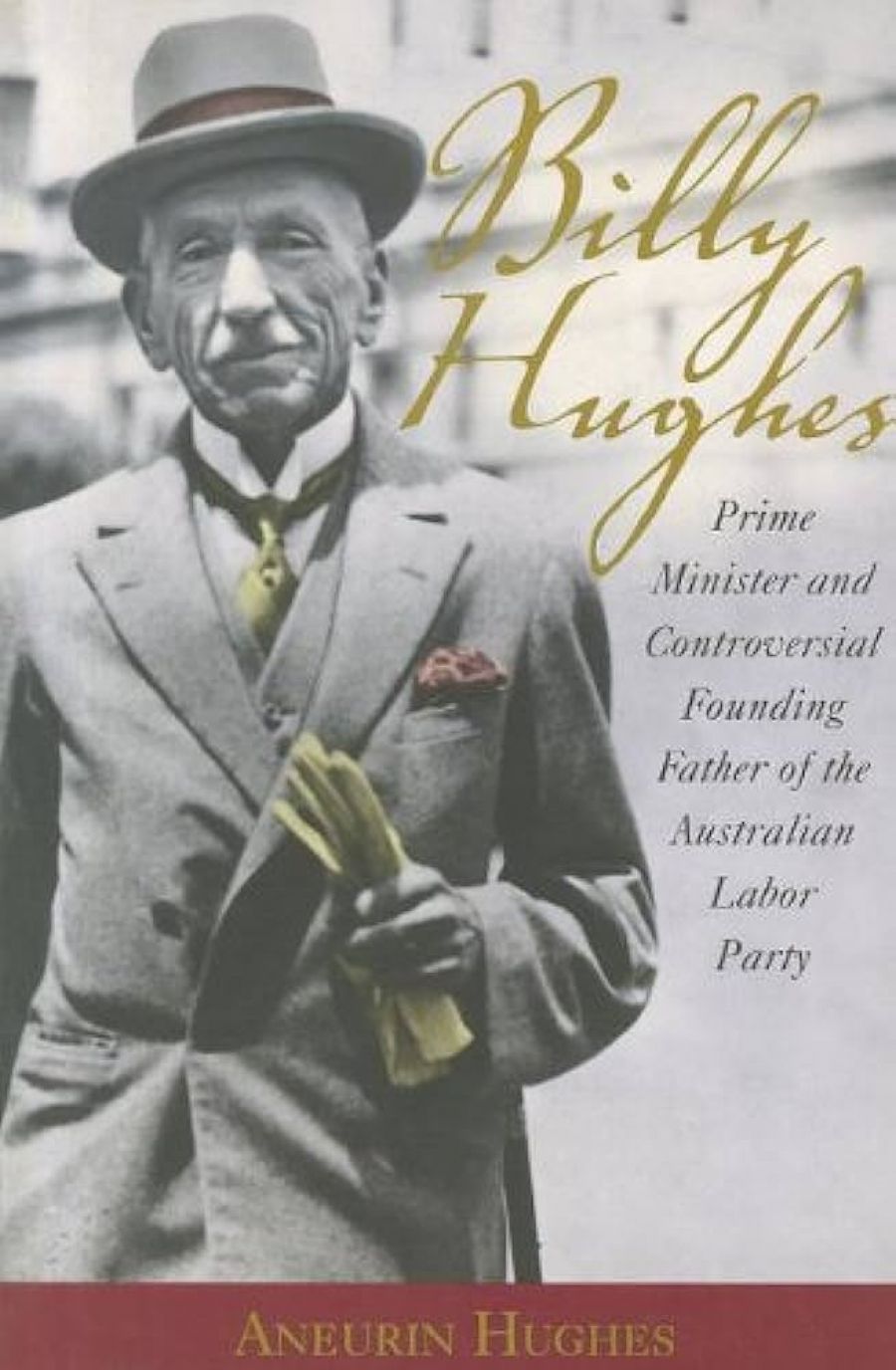

- Book 1 Title: Billy Hughes

- Book 1 Subtitle: Prime Minister and controversial founding father of the Australian Labor Party

- Book 1 Biblio: Wiley, $29.95 pb, 176 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

This is not the story of Billy Hughes the ‘king rat’, the pathological liar, the deluded megalomaniac, the assassin, the ‘little wrecker’, the wily politician without a skerrick of principle. The Billy we thought we knew is almost absent from this short life. Here we have Hughes depicted as a roving Welsh diplomat who happens to work his way up through the jurisdiction of Australia, aiming to be taken seriously by his betters in the British establishment.

In Aneurin Hughes’s stylishly written account, Billy Hughes is an enigmatic old duffer, pottering around the house in slippers and underwear, a tireless worker for others, occasionally forgetful, moving in and out of friendships, while retaining a genteel demeanour to the end. He is a benign if miserly patriarch (he was once described as ‘mean as catshit’) who somehow weaves a melancholic and complicated private life. If Hughes is motivated by public attention to speak on behalf of others, his family dependants shun the lime-light and are motivated by baser instincts – themselves, their own homely worlds, begging money and cash allowances from ‘dada’, and a legion of family complaints. None of his four daughters ever chose to work (although some tried their hand at art) and only one married, and his two sons and one stepson all needed their father’s assistance to secure some form of employment after the Great War. An extended family, always dependent and subject to ailment, seems to have been his greatest blessing.

Aneurin Hughes tells us that he intended to write a personal account; to complement the public accounts of his subject’s political career. He dismisses Donald Horne’s cultural interpretations (In Search of Billy Hughes, 1979) as ‘acidulous’, and L.F. Fitzhardinge’s two-volume biography (1964, 1979) as just a political study (although Fitzhardinge did note one of the difficulties he faced was that few personal records had survived in the archives – something that did not discourage Aneurin Hughes but that leaves many holes in his own study). W. Farmer Whyte’s earlier historical study (1957) is written off as ‘not very accurate’. Other bio-graphers or their preferred interpretations are not mentioned, nor does Hughes discuss how his reinterpretation differs from existing portraits.

This is surprising given that Hughes recycles many observations and events already contained in the standard biographies. Famous quotes reappear, colleagues’ observations are recalled, and pen-portraits of family, friends and political colleagues reappear. Moreover, apart from an occasional interview with surviving descendants and family friends, there is no new material. Like Fitzhardinge, Hughes found few rich veins of information in his subject’s personal papers, an odd letter here and there – often with the reply missing – leaving the author to guess at the context or significance. This means we are often presented with speculation in place of some tangible evidence, as in ‘he could have … he might have’. Many of the fifteen chapters form a set of loosely related essays recounting the important personal aspects of Billy Hughes’s life, including extended family disputes. Only a skeletal political story is presented, one largely deriving from earlier works.

There is a strange fascination with where Hughes went, what he ate, his deafness, his money management, what ailed him. At times, the book is more a travelogue of his trips and escapades, recounting the important people he met and with whom he exchanged opinions, especially overseas (London in particular). The author (perhaps like his namesake) displays a certain Anglo-Welshcentricity, deeming it significant if Hughes meets British aristocrats or is recognised by the London political establishment. There is a sympathetic and sentimental bedrock to the book, with many exaggerated incidences of any English or Welsh resonances.

For me, the most intriguing question is why Aneurin Hughes wrote this book. It took considerable application and research. It is lucid and crisply written, though critics may bemoan the occasional resort to trivial detail (what the author spent at a chemist shop etc.). Aneurin Hughes is not Australian (he has spent most of his life as a British or European diplomat), nor is he a trained historian or close student of Australian political history. I was not persuaded by his own explanation of why he began the book: he lived near a Canberra suburb named after Hughes, cricketers were named after him (Bill Lawry among them), television programmes still featured him (presumably under the ANZAC banner), his name regularly appears in newspapers, and Pauline Hanson’s One Nation movement was a throwback to Hughes’s politics. Many other former prime ministers have similar presences and are more talked about than Hughes. Had Aneurin Hughes better explained his motives, it might have given the reader a better point of contextualisation and might have provided a justification for writers other than professional scholars or family members to write ‘short lives’.

Perhaps the book represents a coming to terms with Australia (Aneurin’s newly adopted home), a way of getting to know Australian political culture (he makes occasional jarring references to contemporary politics), or a certain rite of passage, or a chance to ‘do a biography at some leisure’. Perhaps the common surname kindled his interest or the fact that both of them were of Welsh origin and then played in the arenas of complicated diplomatic politics (Billy Hughes remains our only Welsh prime minister and was the last overseas-born incumbent). Whatever the motive, this book adds to the literature on Australia’s political leaders and may encourage other writers to attempt similar personal studies of other notable figures. But Aneurin Hughes’s version of Billy Hughes remains more a journey to find ‘a life’ and to explore a personality than a biography of a political leader. His implicit argument that Hughes was more a duffer than a digger may not convince everyone, but is worth contemplating and will add to the soap opera of the Hughes legacy.

Comments powered by CComment