- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Lots of characters

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In 1961 a young Noeline Brown was playing in Terence Rattigan’s The Sleeping Prince (1954) at the Pocket Playhouse in Sydenham – ‘just across the Princes Highway from Tempe Tip’, as she characteristically locates it – when Vivien Leigh, on tour with the Old Vic, came to see a specially arranged Sunday evening performance. From the moment she emerged from the chauffeured limousine, Leigh was the star of the show. She was, Brown recalls, ‘wearing a gorgeous, waist-length mink jacket’, and ‘there were strands of lustrous pearls and sparkling diamonds on her delicate throat and hands’. Brown, on the other hand, ‘was in a dress my Mum had made’. That contrast, between theatrical elegance and put-upon pathos, has been the essence of Brown’s own style ever since, and the key to her success as a comedian and an actor. She hid under a large picture hat to introduce Mavis Bramston, a parody of English self-assurance, to a bemused public in 1964. At the other end of the register, her world-weary, ‘You’re not wrong, Narelle’, delivered in a way that was both funny and sad, outlived its many iterations on the televised version of The Naked Vicar Show (1977) to become part of the Australian lexicon.

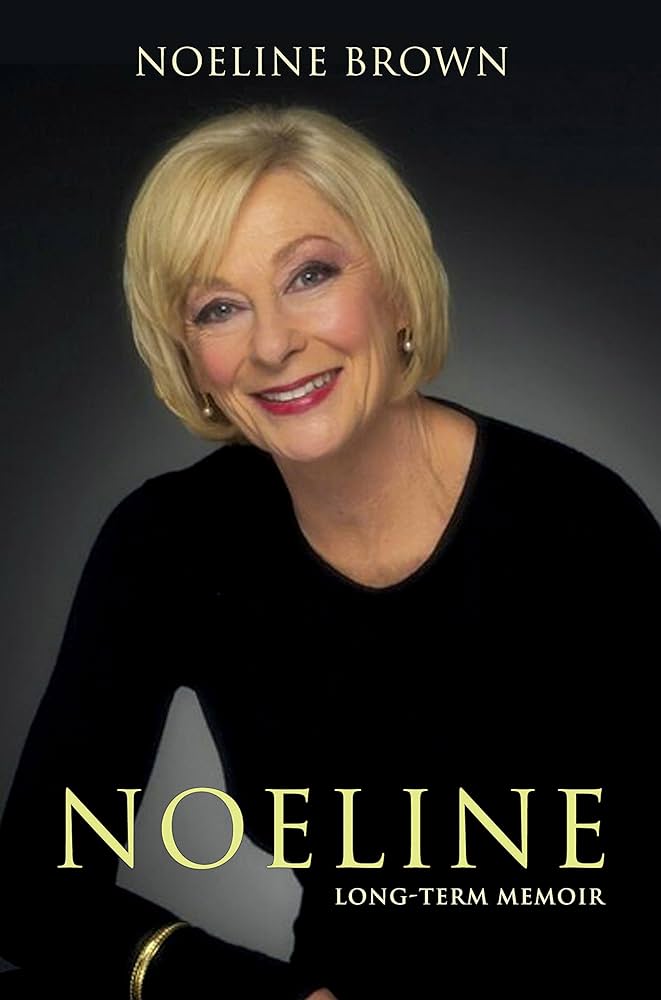

- Book 1 Title: Noeline

- Book 1 Subtitle: Longterm memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.95 pb, 291 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

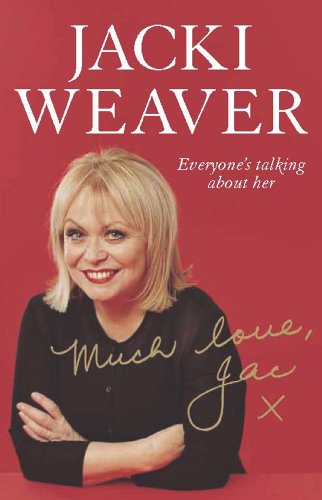

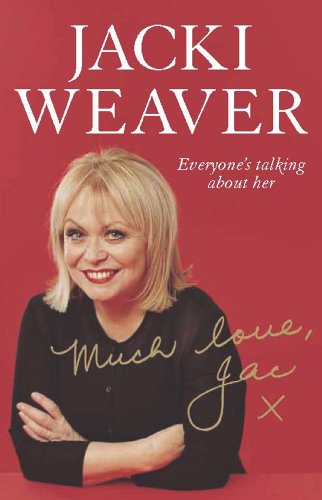

- Book 2 Title: Much Love, Jac X

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $45 hb, 280 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Brown’s Noeline: Longterm Memoir relives these and other highlights, and tells some funny stories along the way, but the stories one would like to have heard remain frustratingly out of reach. Things begin well, as such memoirs often do, with sharp recollections of childhood: of growing up in Sydney’s west, of affection for family that is entirely unfeigned, of making frills for her mother’s Christmas cakes by means of ‘hundreds of little scissor cuts into layers of folded white paper’ – all observed with an eye alert to anything that might be construed as pretentious, like ‘chicken maryland, which was nothing more exotic than a chook and a banana’.

For the most part, however, there is a problem with continuity and depth of field. People come and go with startling speed, even when, as in the sole reference to ‘a very nice Bathurst boy called Max, with whom I kept up a correspondence for well over forty years’, they apparently stuck around. Ralph Peterson, the writer of My Name’s McGooley, What’s Yours? (1967) ‘went bush’. Her agent ‘went bust’. Her relationship with Robert Hughes ended for reasons that, like the relationship itself, are never really explained. On one of Hughes’s visits to Australia, to undertake research for The Fatal Shore (1987), they run into one another by chance and arrange to meet later for coffee: ‘By the time I returned, Bob had disappeared. That was the very last time I saw him.’

Most oddly of all, the political dimension to Brown’s life, which was substantial enough to lead her to stand (unsuccessfully, but not by much) as a state Labor candidate in the Southern Highlands in 1999 and again in 2003, is glossed over. Her candidacy is presented as a piece of unexpected casting, a role in which she appears, by her own account, to have been uncomfortable. When the opportunity arises, elsewhere in the book, to explore the political dimension, she skirts widely around it. In describing her first television role, in an ill-fated drama series called Jonah (1962), she tells how it ‘ran into trouble with Actors’ Equity over some sort of industrial dispute’, an airy and passing reference that seems in ‘character’ rather than character. Bangladesh, which she visits in 1985 for World Vision, is little more than a set, ‘very green’, with a ‘vast river running though it’.

There are some striking similarities between Brown’s life and that of her friend Jacki Weaver, as Weaver records it in her Much Love, Jac X. There are the same kinds of fond memories of loving and close-knit families, and of being the naughtiest girls in the class, show-offs who, in the eyes of everyone they knew, were destined for careers on the stage. Weaver certainly took that view of herself, and from very early on. She recalls being labelled at the age of five as a ‘real character’ and ‘thinking, no, no, I’m lots of characters’. And again like Brown, of ‘You’re not wrong’ fame, Weaver relates how ‘strangers still come up to me and quote’ her line from the film Caddie (1976), ‘Life’s a bugger’. It is fitting, given the resilience that Weaver and Brown have displayed throughout their lives and careers, that both women are so closely associated with lines that celebrate a certain kind of laconic Australian fortitude, a determination to go on in the face of what cannot be explained or understood.

In telling her life story, Weaver is the more furiously upbeat of the two, and it is not long before the strain begins to show, particularly when it comes to events that it would be very difficult for anyone to be upbeat about. She reveals how she was regularly abused, from the age of seven, by a friend of the family, until she summoned up the courage five years later to threaten him by saying that it had to stop or she would tell. It did stop and, for the most part, she didn’t tell. ‘Apart from confiding in a few close friends, I’ve kept it secret for more than fifty years, even from my parents, my brother and my son.’ And then, having raised the subject, she drops it just as quickly, with the curious observation that ‘it shall remain within the pages of this book’.

Weaver is indeed lots of characters, and here they jostle one another for space. She is a self-confessed luvvie – ‘I love her’, she says of someone who has a walk-on part, and ‘I love her’ again, only two paragraphs later, this time of the producer Margaret Fink. But it isn’t as simple as that. When Fink keeps her waiting for a prearranged meeting, and then cries off, it is clear that Weaver still feels hurt and resentful, years after the incident. Her affection for her immediate family – parents, brother, son – is clear and unequivocal, but it would take forensic skills of a high order to work out exactly what is being said about some of the key figures in her professional and personal life, and whether she resents or admires them, loves them or hates them. Weaver would doubtless say that that’s the way it is, and doubtless it is, but it makes for a bumpy read and an impression of sassiness uncomfortably at odds with self-doubt.

There is a history to be written of Australian performance in the 1960s and 1970s, in which Brown and Weaver, for whom these decades were crucial in building their careers and reputations, will have leading parts. It was a time of remarkable energy and inventiveness, with revue and music hall, film, television and theatre all sparking off one another. Both these memoirs provide glimpses into that world, but the anecdotes don’t really join up, so that what was so special about it, and why its influence is still being felt, remain disappointingly elusive.

Comments powered by CComment