- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Australian gothic

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Here is a rich vein of strange rococo fantasy in recent Australian fiction. Tom Gilling (The Sooterkin, 1999), Andrew Lindsay (The Breadmaker’s Carnival, 1998, and The Slapping Man, 2003) and Gregory Day (The Patron Saint of Eels, 2005) have all imagined tragicomic country towns in which miracles and monsters infiltrate the sleepy lives of unsuspecting villagers. The genre can be a trap for inattentive authors: the lines between quirky and cute, touching and twee, are perilously easy to cross. With this comic apocalyptic fantasy, Catherine Rey – who writes in French but lives in Perth – avoids this trap and achieves something more. In an idiom that is part Rabelais, part Old Testament and part Ocker Pub, she creates an hilarious, troubling fable with a distinctly Australian taste.

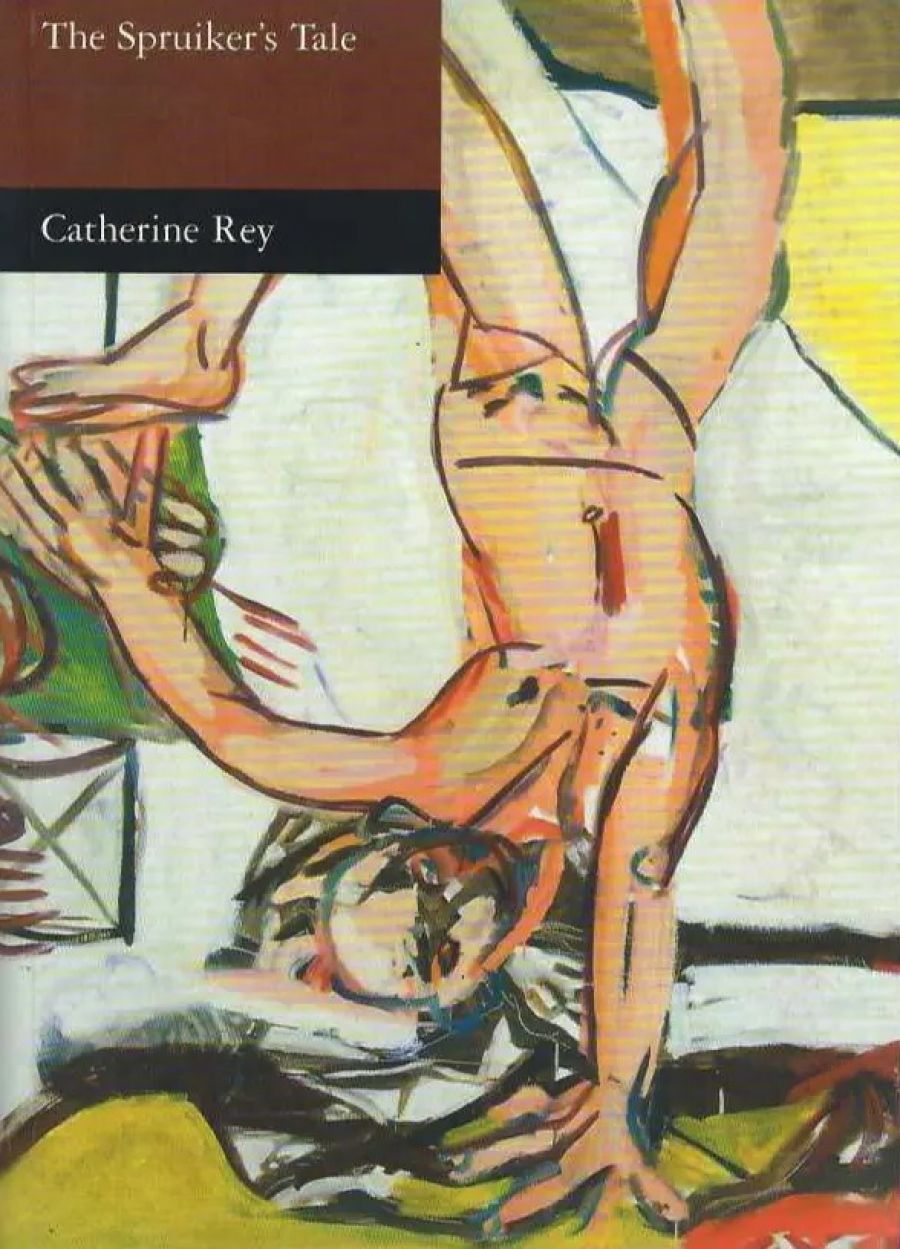

- Book 1 Title: The Spruiker’s Tale

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $24.95 pb, 262 pp, 1920882073

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The novel tells the story of the Nagalingams, a family of former circus performers headed by the magnificently horrible Magnolita Rosaria. After a glorious career on the flying trapeze, Magnolita has run to fat. Foul-mouthed, vain and volatile, she retires with her three grown sons to a rundown town on the edge of the Gibson Desert. Holding drunken court in their filthy shack, she is as fascinating and grotesque as anything in Roald Dahl’s children’s stories. She primps and preens, hoards scraps of meat in her mattress and pampers her hideous sons. Her scorned, sweet-natured, centenarian husband lies swaddled and forgotten on the verandah. Her granddaughter bides her time in glowering obedience, despised and abused by her philistine family.

All this is told in a complex, teasing patois by Jones, the spruiker of the book’s title. The reader of a translation is bound to feel that she is doing the original an injustice – that she is missing important references, overlooking some vital influence, not entirely getting the joke. No doubt this applies to The Spruiker’s Tale (Ce que racontait Jones in the original French), a book so rich in allusion – even in translation – that one can only guess at what further complexities might have been lost in the translating. To Andrew Riemer’s credit, this question is largely drowned out by the ribald voice of the narrator, Jones; whatever Gallic puns we might be missing, there is more than enough to keep us occupied in his sideshow soothsayer’s English. Rabelais is an un-mistakable influence. Nostalgic for a particularly alluring circus lady, Jones could be channelling Pantagruel himself: ‘Ah! My dinger starts donging like mad when I remember how beautiful she was … this precious vase, which spread out from a narrow waist to a bosom well-endowed with two generous breasts, at which every bastard begged for alms.’

The story itself is full of familiar echoes. There are elements of fairy tale: the three dutiful sons, dispersed to pursue their suitably archaic vocations (soldier, farmer, priest); the ill-used daughter-in-law, cooking and cleaning for a lazy, spiteful mother-in-law; the motherless child, clothed in rags and made to sleep in a cupboard, who outwits and out-swindles her cunning, greedy captor. Other twists recall a slightly farcical gothic western: strange omens appear, barns and churches catch fire, livestock is mutilated and a young girl is found dead. The sheriff arrives, vigilantes gather, the mob seeks justice. This sort of thing is the meat and potatoes of much southern – and Australian – gothic, but here it is absorbed into Rey’s more ambitious, more original vision.

Against the barren backdrop of the Gibson Desert, these mythic, conventional elements are thrown into sharp relief. Pitted against the West Australian townsfolk, the grotesque Nagalingams seem engaged in an epic moral struggle, the significance of which is not always easy to de-cipher. The Nagalingams are inarguably horrible: they are vile, cruel, hateful, selfish, stewing in their smelly Oedipal juices. For all this, however, Jones expresses little disapproval of their crimes against the villagers; his outrage at their perversity never seems entirely sincere. Jones describes the villagers’ quest for justice coldly: not as though he believes the Nagalingams should escape punishment, but as though he is not convinced that the villagers are in a position to judge their neighbours.

Perhaps, more to the point, he believes that none of these earthly crimes is really important. Halfway through his story, he pauses to recount a strange and pessimistic parable in which God is a fickle magistrate who has misplaced his record book and so casts all of humanity, sinners and saints together, into the flames of hell. Whatever you do, Jones seems to prophesise in his debased Old Testament English, you will likely be damned by His callous, impatient judgment.

The Final Judgment may be unreliable, but Jones’s characters certainly get their earthly come-uppance: suffice to say that none ends happily. Jones, however, takes little satisfaction from the family’s demise. If this were a Roald Dahl story, he would administer vicious poetic justice with one of his brutally apposite twists in the tale. Jones, however, metes out a more subtle punishment. His poetic justice lies not so much in the messy end that befalls Magnolita Rosaria as in a subtle stylistic shift that strips the Nagalingams of their moral and literary power. Alone in the desert, Magnolita and her clan seemed like figures in an epic archetypal drama. When, in the book’s final pages, Magnolita finally ventures beyond her ramshackle queendom and into the quotidian world of the big city, the lights come up and we see her for what she is: a batty, sad old woman in moth-eaten circus clothes and gaudy make-up.

This is not to give away the ending: more adventures await this diminished Magnolita before the story ends. This is a strange, disturbing, wonderfully funny book from a writer who demands our close attention. In Andrew Riemer, she has found the champion and translator she deserves.

Comments powered by CComment