- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Spence at last

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As Nicholas Jose observed in the November 2005 issue of ABR, the face of South Australian novelist Catherine Spence, currently featured on our $5 note, circulates much more widely than any of her books. Like those of several other nineteenth-century Australian women writers, Spence’s novels were revived in the 1980s but are now once again out of print. So this new edition of her autobiography, extensively annotated and accompanied by letters and a diary never before published, is especially welcome.

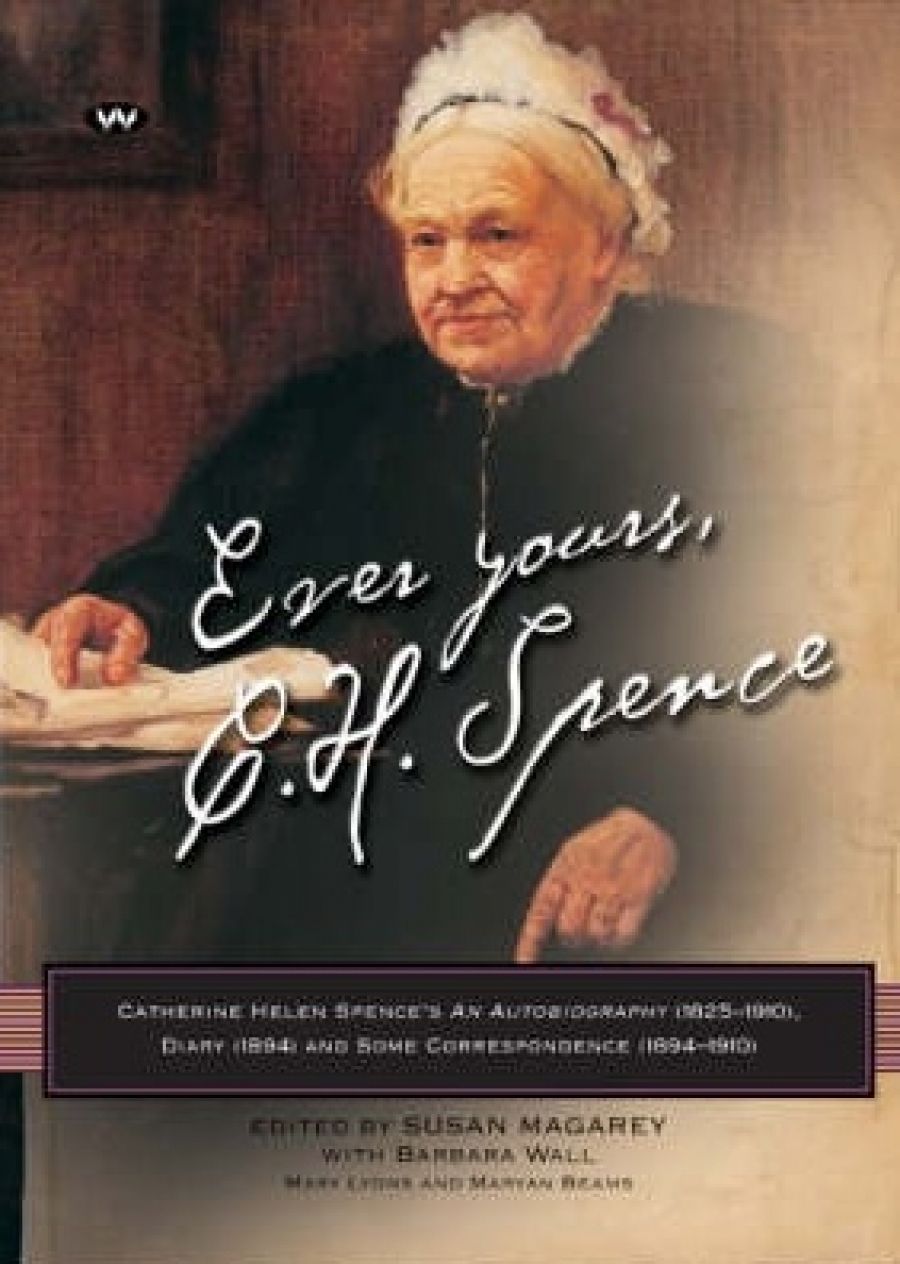

- Book 1 Title: Ever Yours, C.H. Spence

- Book 1 Subtitle: Catherine Helen Spence’s an autobiography (1825–1910), diary (1894) and some correspondence (1894–1910)

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield, $39.95 hb, 392 pp, 1862546568

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Unlike Mary Gilmore and Banjo Paterson, Spence appears on our currency because of her political rather than literary activities. Her novels were mainly written in the first half of her life of eighty-five years. As she notes in the autobiography, even when first published they were not bestsellers, and she ‘found journalism a better paying business for me than novel writing’; she also felt her best work was done in her articles, essays and reviews. When Spence began writing in the late 1840s, more public spaces were not open to women. She was one of those who helped to change this, giving numerous lectures and sermons as well as writing for the media. Although Spence devoted hours of work to children’s welfare and education, the cause closest to her heart was the campaign for effective voting, which to her meant the use of the Hare-Spence system of proportional representation.

As we see from a letter to Alice Henry included in this volume, Spence, inspired by her reading of Mrs Oliphant’s autobiography, began writing her own in late January 1910, only two months before her death in early April. She notes in her next letter that she had written about 50,000 words in six weeks, an indication of her remarkable energy and fluency as a writer, even in old age. However, she did not finish her life story, dying while writing the sixteenth of its twenty-four chapters. The autobiography was completed by her friend Jeanne F. Young; although still written in the first person, and based on entries in Spence’s diaries, there is a noticeable change in tone and style. Frustratingly, for many years it appeared that the original diaries were then destroyed.

Susan Magarey, who searched fruitlessly for the diaries when writing her prize-winning biography of Spence (Unbridling the Tongues of Women, 1985), later discovered that the 1894 diary had survived in a private collection. In 1989 she was allowed to borrow it for a week to make notes; these, with some inevitable errors and lacunae because of difficulties in reading Spence’s handwriting in the limited time allowed, are now printed for the first time. In 1894 Spence was on the second leg of a two-year visit to America, England and Europe, seeing friends and relatives, promoting effective voting, and all the time busily writing and lecturing in an attempt to cover as many of her costs as possible. On April 2 she recorded that in the past month she had written ‘230 sheets or pages larger or smaller besides articles and the draft of story and 100 letters’. Little wonder that the entry for the previous day had ended with the words ‘pretty tired’ – she was, after all, nearing seventy.

While An Autobiography provides us with Spence’s overview of her life and times, the letters and especially the diary take us closer to what it meant to be Catherine Spence. Admissions of weakness are few. In London, she falls and dislocates her right shoulder; the doctor ‘had three wrenches at it but did not get it in place – Pretty bad night!!!’ The next day her shoulder is set ‘under chloroform ... and I felt greatly relieved’. A few days later, she is writing letters and diary entries in pencil and still determined to spend time in Italy with her good friend from Adelaide, the novelist Catherine Martin, before returning to Australia.

Writing in 1907 to Alice Henry, who was then sharing a house in Chicago with Miles Franklin, Spence comments that ‘My Brilliant Career though very clever was depressing’. It is therefore interesting to compare Franklin’s letters and diaries with Spence’s. While Franklin’s letters are usually full of wit and sparkle, her diary entries reveal that she was, indeed, often deeply depressed. Spence’s, however, show the toughness, resilience and optimistic spirit that enabled her to achieve so many firsts in her life. One can only hope that more of her diaries have survived and will eventually be made public.

Congratulations to Susan Magarey, and her collaborators Barbara Wall, Mary Lyons and Maryan Beams, for their research, transcriptions and annotations, which provide an invaluable historical context for Spence’s words. And congratulations to Wakefield Press for this handsome volume, with its many illustrations, including a cover portrait of Spence by Margaret Preston.

Comments powered by CComment