- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Subheading: Henry Handel Richardson’s 'The Fortunes of Richard Mahony'

- Custom Article Title: ‘Another Colosse on hand'

- Review Article: No

- Article Title: ‘Another Colosse on hand'

- Article Subtitle: Henry Handel Richardson’s 'The Fortunes of Richard Mahony'

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The year was 1911. Four months after beginning work on a new novel, Henry Handel Richardson admitted to herself the ambitious scope of her new project: ‘I have another Colosse on hand, & it begins to grow, though slowly.’ This aptly nicknamed project was eventually to become the trilogy we know as The Fortunes of Richard Mahony, which was to occupy its author for the next twenty years. Length is not synonymous with ‘greatness’, of course. At almost eleven hundred printed pages, some readers have resented its bulk. At the same time, relatively few have had the opportunity to read the original volumes. Others have been puzzled by its combination of naturalism and allegory, and many more have been struck by an epic quality in its scope and vision. Kylie Tennant assured her readers in 1973 that ‘should any TV producer ever … take the great myth of Richard Mahony into the television medium, a new generation would discover that Mahony is not just a piece of Victorian literary furniture, but has the same weird power to grip an audience as Hamlet or Lear. For if ever there was a myth figure it was Richard Mahony.’ Richardson herself believed that her intention had been ‘to treat the chief features of colonial life in epic fashion’. Dorothy Green argued in 1970 that the novel should be seen as ‘not merely an emigrant novel of early colonial Victoria, but … [as] a part of the intellectual history of European civilisation in the nineteenth century.’ Even so, Michael Gow condensed this epic into a 66-page, two-act, domesticated playscript, performed at the Brisbane Powerhouse and the Melbourne CUB Malthouse in 2002.

Richardson had begun thinking about the new project within a week of receiving copies of her previous, shortest and favourite novel, The Getting of Wisdom, on 11 October 1910. This semi-fictional version of her Australian childhood and adolescence had led her to a much more ambitious narrative centred not on herself but on a founding national narrative seen through the letters written between her parents, Walter and Mary Richardson, during a thirty-year period starting in 1854. This was the period of the gold rush, sixteen years before Richardson’s own birth, in the half-century that was to witness the forging of a nation from a collection of colonies. The fictional and Irish-born Richard Mahony – doctor, failed digger, successful storekeeper, husband of Mary, father of Cuffy, Alicia and Lucie, would-be gentleman and reluctant doctor again – is at the centre of the trilogy, but he does not dominate our interest until the third and final part. Social and psychological themes are refracted through his terrible restlessness. Mahony’s determination to better himself, to match social success in the new colony of Victoria with his notion of a lost birthright to Irish gentility, is at odds with a vigorous colonial materialism (a plutocracy) busy about either replicating or scorning the class system of the ‘Mother Country’. Alienation from his immediate surroundings becomes Mahony’s normal state.

As a matter of record, and as a measure of her authorial and historical detachment, Richardson later informed Nettie Palmer that except in

two places in the Trilogy I speak entirely for the generation of whom the books are written. One of these is the Proem to Australia Felix; the second, the few sentences about the Bush & its colouring that occur in the first chapter of Ultima Thule. All the old settlers term the landscape colourless, the Bush silent. And for the time being their standpoint had to be mine.

The Australian subject and setting of the novel have been interpreted at a more generic level as a narrative of settler colonialism, certainly so when read outside of a British or Australian readership and by another settler-colonial readership. One of the earliest reviews of Ultima Thule (1929), by Henry Hazlitt in the New York Sun, opined that it would be difficult to find ‘a more vivid description of pioneer Australia – of the bush, of the heat, the intolerable summers, the physical aspect of the small towns, the kind of people who lived there … pioneer ways and the pioneer soul … the contempt for social formality of any kind or even the ordinary social graces’, and that the national image in this novel was ‘strikingly like that of our own Far West but a generation or two ago’. The point was repeated in his review of Australia Felix (1917), that ‘to the cultured European eye our architectural landscape wears a provisional, jerry-built, and impermanent air; and it remains, of course, in full flower in our glorification of business and material progress’. Richard Mahony himself could have written that sentence.

Each of Richardson’s three volumes appeared at widely spaced and, from a literary point of view, inauspicious and turbulent moments in European history. The first volume, Australia Felix, appeared in the middle of World War I, in the same year as T.S. Eliot’s ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’, James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and Lenin’s Imperialism: the State and Revolution. The second, The Way Home, and third, Ultima Thule, appeared in the Depression years of 1925 and 1929, respectively: the former in the same year as Virginia Woolf’s The Common Reader and Mrs Dalloway; the latter, in Australia, alongside David Unaipon’s Native Legends, Katharine Susannah Prichard’s Coonardoo and the first of Arthur Upfield’s Inspector Napoleon Bonaparte detective novels. At one stage, and as a trace of her intention to write the biography of a nation through a family saga, Richardson had planned to add a fourth volume bringing the story up to the Gallipoli campaign of 1915, a military defeat for Britain and her allies, now commonly regarded as a seminal moment in the formation of the Australian national imaginary. Four chapters of this abandoned novel survived, and they were published as a continuation of the life of Cuffy Mahony in Richardson’s collection of short stories, The End of a Childhood, in 1934.

Most modern readers have made their acquaintance with the trilogy through the numerous editions of the omnibus volume first published by Heinemann on 18 November 1930, a direct result of the huge commercial success of Ultima Thule. It was Richardson herself who undertook the task of cutting about 100 pages from the original texts, and her cuts ran into many thousands.

In the United States, the three-volume paperback published by Norton & Co. in 1962 was a mixture of texts: Australia Felix is different from the first Norton edition (a resetting of the original first editions). The paperback Fortunes of Richard Mahony brought out by Penguin in 1971, on the other hand, and in spite of what is tacitly implied to the contrary, is a reset reprint of the cut-down omnibus version of the trilogy text, issued, somewhat misleadingly, in three separate volumes. The Penguin edition was not available for sale in the United States. Most Australian readers discovered Richardson’s works very late, after The Way Home and not before Ultima Thule had made her work retrospectively world-famous in 1929. It was for this latter audience that Heinemann published the omnibus edition, in England and Australia, in 1930. Consequently, the first volume, the most ‘Australian’ as well as the most drastically cut of the three volumes, remained largely unavailable and unread, particularly in her home country, because of the wartime conditions of its first publication thirteen years previously. On 24 March 1930 she wrote to Mary Kernot about her gruelling labour on the omnibus:

Day after day I have been at work on the Mahonys, all three Vols of them, scanning each comma & semicolon. From the first Book I have deleted about 12,000 words. It is longer a good deal than its two companions, & hasn’t I think lost by the cutting. It doesn’t do for there to be any over-lapping when the three are between the same pair of boards, nor must Vol I detract from the effect aimed at in Vol III. Well, it was a piece of work no one but myself could do – & I have done it, to the best of my ability. Though with groans.

Fifteen thousand copies sold on the day of publication (18 November 1930), and an immediate reprinting of 20,000 copies was begun.

As it stands now, The Fortunes of Richard Mahony is often regarded as ‘the great Australian novel’. Richardson herself had little patience with or interest in such an accolade, and in any event saw her trilogy as a contribution to what she thought of as a distinctly European genre of novel writing. Even so, its prominence in the canon of Australian literature is indisputable, and it has been valued not only for its own sake but also as the benchmark against which the very idea of a national canon has been constructed. In her wartime broadcast on Australian women writers in 1941, Nettie Palmer proposed that Richardson had not only ‘told unsurpassably the necessary, typical story of the sensitive European – an Anglo-Irish doctor, in this case – who comes to our new crude Australia Felix in its days of gold-fever’, but that the book itself ‘in its universal acceptance as a masterpiece, has definitely raised the hopes of our literature, both among writers and readers’. A first draft of the ‘First Part’ of what was to become Australia Felix was completed in London, by 17 May 1911. By July, Richardson expected to have 150 pages done, and by October she saw clearly what might be called the ideological shape and temper of the novel as a whole: ‘Like Maurice [Guest] this, too, will be a story of a gradual disillusionment; with this difference, that it covers twenty years of a man’s life, & that this man’s only schuld is a rigid seeking after truth. But I hope I shall manage to let his history end in a ray of light – not in the gloom of M.G. [Maurice Guest].’ Her sources were of two kinds: her parents’ letters, together with recollections of her mother’s stories, and the published records available in historical texts, memoirs, maps and newspapers of the period, most of which were made available to her in the British Library.

Richardson determined that the whole volume had to be ‘blocked out in its first form’ before she made her one and only return visit to Australia. She was for a time distracted by her sister Lil’s suffragist activities (which eventually landed her in jail), but nevertheless had completed 300 typed pages by 28 March 1912. She already knew that she was ‘many months distant – or even years – from my ending’. On June 2, she announced her decision to split the narrative into two separate volumes, and also revealed her characteristically dogged and painstaking progress – ‘nulla dies sine linea’. Even so, she left for Australia on 2 August 1912, accompanied by her husband, John George Robertson, Lil and her young nephew, Walter Lindesay Neustätter. She revisited locations in the novel – Melbourne, Geelong, Castlemaine, Maldon, Ballarat, Queenscliff, Koroit and Chiltern – and also stayed in the Dandenongs, east of Melbourne, at the Upalong home of her schoolfriend and lifelong correspondent Mary Kernot.

A month after her return to London, on 23 November 1912, Richardson was envisaging publication in 1913. Five chapters were in final form when her typist, Irene Stumpp, fell ill. The book ‘has grown under my hands – my books always seem to do that’, she wryly admitted. In mid April, she read the first seven chapters to her immediate circle (including her husband – always her first and most important critic – and Lil). By May, she was well into Part Two, and had planned for a total of forty chapters, none more than twelve pages in length, containing forty characters and covering a period of sixteen years. That the two volumes were stretching to a third was first revealed to the French translator of Maurice Guest (30 May 1913), as was the announcement of a collective title, Australia Felix – the name first used by Major Mitchell in 1836 of an area south of the Murray River, in reference to what is now the state of Victoria, ‘the first name given to the inhabited part of the colony’.

The subtitle for the first volume now bore the name of the principal character, ‘Richard Mahony’ (pronounced Mahn-y). From Melbourne, Mary Kernot sent Richardson Henry Gyles Turner’s new book on the Ballarat miners’ uprising at Eureka Stockade, Our Own Little Rebellion (1913), particularly valuable because of ‘the Australian point of view’, in Richardson’s words. Towards the end of June, Heinemann was enquiring about the date on which they might expect to receive the finished typescript.

Except when she was on holiday overseas (generally this meant two to four weeks in Germany or Switzerland in the spring or summer), Richardson’s habit was to write every morning until lunch, then walk in Regent’s Park every afternoon, thinking over the paragraph or chapter to come. The first chapter of Part Two gave her particular difficulty (‘the hardest chapter in the whole book’), and in November she was ‘deep in medical books’. Part Two was not finished until the following Easter. The war also affected its composition – ‘the pages go up & down with the Fall of Antwerp’, she observed on 11 October 1914. On December 3, she wrote: ‘It’s on the point of conclusion – another month will do it – & then I shall put it to bye bye till the war’s done. I can’t understand people (writing people) publishing books just now. No-one has an undivided brain to read them with. I know I myself am sodden with many newspapers.’ For a specific and typical insight into her own working pattern, the following is an extract from her diary for the last three months of revision and rewriting:

March 8 Worked, Tangye Chapter [Part IV, 3]

9 Worked, Odd pars.

10 Worked, Odd pars. Bad day.

11 Worked: Odd pars & Tangye. Nothing special.

14 Worked. Tangye & last odd par.

15 Worked. Poor.

16 Worked. Awful.

22 Worked. Last odd par finished.

23 Worked Tangye.

April 19 Hard at work: house [Part IV, 12].

24 Nub read chapter VII [Mahony’s fall from the horse and subsequent illness].

May 6 Worked.

10 Worked.

11 Worked. Typed.

25 Finish.

28 Finished Aust. Felix Book I. Champagne for dinner.

The book was finally published on 23 August 1917 as The Fortunes of Richard Mahony, Volume I, Australia Felix. Richardson’s satisfaction at its appearance, sales figures and a second impression in November was tempered by four considerations: the knowledge that she herself conceived of it as ‘a mere prelude’ to the second volume, ‘the real thing, the book I wanted to write’; the irritating but legally necessary obligation to rewrite part of a paragraph in order to avoid a possible libel suit instigated by the ex-proprietor of the Ballarat Star; further irritation when her carefully guarded private identity was promptly revealed by the Chicago Tribune of 16 September, when it trumpeted: ‘He’s a woman!’; and the appearance of an American edition, published by Henry Holt (New York), which included the original, offending paragraph but omitted the words ‘End of Book One’ on its final page, thus leaving its American readers wondering about what might become of Mahony and his family as they leave Melbourne on their apparently triumphal voyage back to the ‘Mother Country’.

All readers would have to wait for another eight years to find out what happened next. Some of those had read its predecessor, but none knew what was to follow. In July 1922 no fewer than 300 pages of the second volume had been written, with another hundred to be completed before the planned publication in the autumn of 1924. Yet, without William Heinemann at the helm to make it a priority (he had died in 1920, but had stated that ‘This book will still be here when we are all of us under the sod’), the novel had to take its turn in the publication schedule, and it finally appeared on 7 June 1925 as The Way Home being the Second Part of The Chronicle of The Fortunes of Richard Mahony.

The third volume, what Richardson called her ‘incubus’, was written up to the end of Part Two by 20 September 1926, and by April of the next year she had completed twenty-three of the thirty chapters. She wrote to Mary Kernot:

I fear Vol. III is going to be something of a disappointment … The story is Mahony’s story, follows his tragedy, & ends with his death … Somewhere in the background of my mind floats Cuffy’s fate, in a nebulous way. Had I time – & health – I shd have finished my epic – perhaps at Gallipoli – but I don’t think that will now ever come to pass … Hence you see, Cuffy can play no more than a minor part in Vol. III, & will be left suspended in the air, at the end, as a child of nine or ten. The trilogy closes with Mahony’s death.

She had determined not to attempt a fourth volume out of fear of what she called the ‘pedestrian woodenness’ of a lengthy family history in the manner and style of the later Galsworthy. On 28 December 1927 she therefore wrote ‘Finis’ under the last words of the trilogy, and immediately set about revising it.

Heinemann received the finished typescript in mid July of 1928. Its ‘stark undiluted tragedy has somewhat horrified them’, she believed. What she did not reveal was the perhaps even more horrifying news that Heinemann had declined to bear any of the cost of publishing Ultima Thule. John George Robertson had undertaken all the responsibility for business contacts between Richardson and her publisher, and at some point in early July (in an unrecovered letter) he had offered some financial contribution towards publication costs. On 13 July 1928 Heinemann’s chairman, Theodore Byard, replied with a counter-offer:

I very much regret to say that the unanimous opinion here is that your wife’s book, ULTIMA THULE, has practically no prospect of sale. I have gone carefully into the figures of THE WAY HOME and that book shows a loss of £65, allowing for absolutely no overhead expenses of publication. I have not got the figures of the first book of the trilogy but I fear the situation is much the same with regard to that. I am afraid, therefore, that if you want us to publish the book, we shall have to ask you to bear the cost of production. I gather from your letter that you are willing to do this, and if you will confirm this, I will have an estimate prepared and sent to you. It is one of the trying things of a publisher’s profession that he is bound to consider sales very carefully and not take books on their merits alone.

Ten days later, Byard came up with an estimate of production costs: for 1000 copies, Robertson would be charged £165.10s, plus an additional sum of £25 to cover advertising costs. After attending to proof corrections in October, November and December, Richardson saw the final volume of her trilogy published on 10 January 1929 as Ultima Thule being the Third Part of The Chronicle of the Fortunes of Richard Mahony. Seven days later, and as a consequence of excellent reviews, Heinemann was putting a reprint in hand and estimating that a thousand copies might meet the demand, at a cost of £80.11.0.

What happened then must have seemed extraordinary to both publisher and author. In the June issue of the Book Club Journal (New York), Ultima Thule was announced as the September Book of the Month. The first Norton printing of Ultima Thule was 85,000 copies. The title, Richardson explained, echoed ‘a very feeble volume of verse, written by Longfellow in his old age … [and] is to be taken in its widest sense, as meaning “beyond the utmost limits or boundaries”’ (26 July 1928, wrongly dated by Richardson as 1927). Its commercial and international success was beyond her wildest expectations.

If there was one single response that tipped the scales in Britain, and then in Australia, it was Gerald Gould’s Observer review of 13 January 1929: ‘This book is a masterpiece worthy to rank with the grandest and saddest masterpieces of our day – [Israel Zangwill’s 1892 migration novel] Children of the Ghetto and [Arnold Bennett’s 1908] The Old Wives Tale.’ Hardly less grand was Arnold Palmer’s comment in Sphere (19 January 1929) that ‘in these three volumes we have one of the greatest novels not only of our generation but of our language ... I ask myself what English novel can be placed in front of this one ... Richard Mahony has been compared, not inaptly, with King Lear. But I see Henry Handel Richardson as another Balzac, with all the Frenchman’s passion for completeness in breadth and depth and height.’

A keenly anticipated Australian response came in the unsigned Bulletin review of 13 March. It opened unpromisingly – ‘Reading it is often like looking at a rainy week from beneath a wet blanket. It opens gloomily, continues in gloom with very scant relief, and ends in terrible darkness’ – but continued in a very different vein: it was not only ‘one of the greatest novels yet written by an Australian’, but its hundred-page section from 178 to 278 [i.e. Part II, chapter vi to Part III, chapter iv] showed that the novel was ‘a masterpiece for that great passage alone ... a marvellous passage of sustained brilliance ... [wherein Richardson] reaches a height of literary perfection that will not easily be matched in a field a great deal wider than the Australian one’. On April 28, Hugh Walpole confirmed the literary establishment’s approval by announcing, in the New York Herald Tribune, that ‘there is no modern book with which one can compare “Ultima Thule”’.

On April 10, the Sydney Sun published Guy Innes’s lengthy announcement from London that Ultima Thule was ‘the most outstanding achievement of any Australian writer of the present generation’. Nettie Palmer’s moment had come. She assured her readers that the novel had already ‘captured English critics in spite of its subject’ and cited Sylvia Lynd’s comment that ‘What Chekov did in a short story, Henry Handel Richardson has done on a large scale. This colonial doctor’s downfall is like the death of a king’ (‘Our Most Famous Author’, Brisbane Courier, March 30).

Richardson was soon claimed as national literary property. Articles and letters were written about her name, on her male pseudonym, on her schooling at Presbyterian Ladies’ College, on her musical ambitions, on her visit in 1912 and on her views about Australia. One school friend, Dora E. Oakley, filled almost three pages of the Victorian Postal Institute magazine (February 1929) with personal and musical anecdotes. An item among Richardson’s press cuttings, Heinemann’s Galley for March 1929, tells how an order for 600 copies of Ultima Thule was immediately placed by Melbourne agents on the strength of a single, commendatory telephone call. Guy Innes’s London interview with Richardson had been cabled to Melbourne and it broke the ‘news’ of her Australian origin and background. The publicity managers clearly played a key professional role in the promotion of Richardson and her books, but this in no way diminishes the significance of worldwide response to the novels themselves. In the judgment of the anonymous Bulletin reviewer of March 13, an Australian author needed all the help he or she could get.

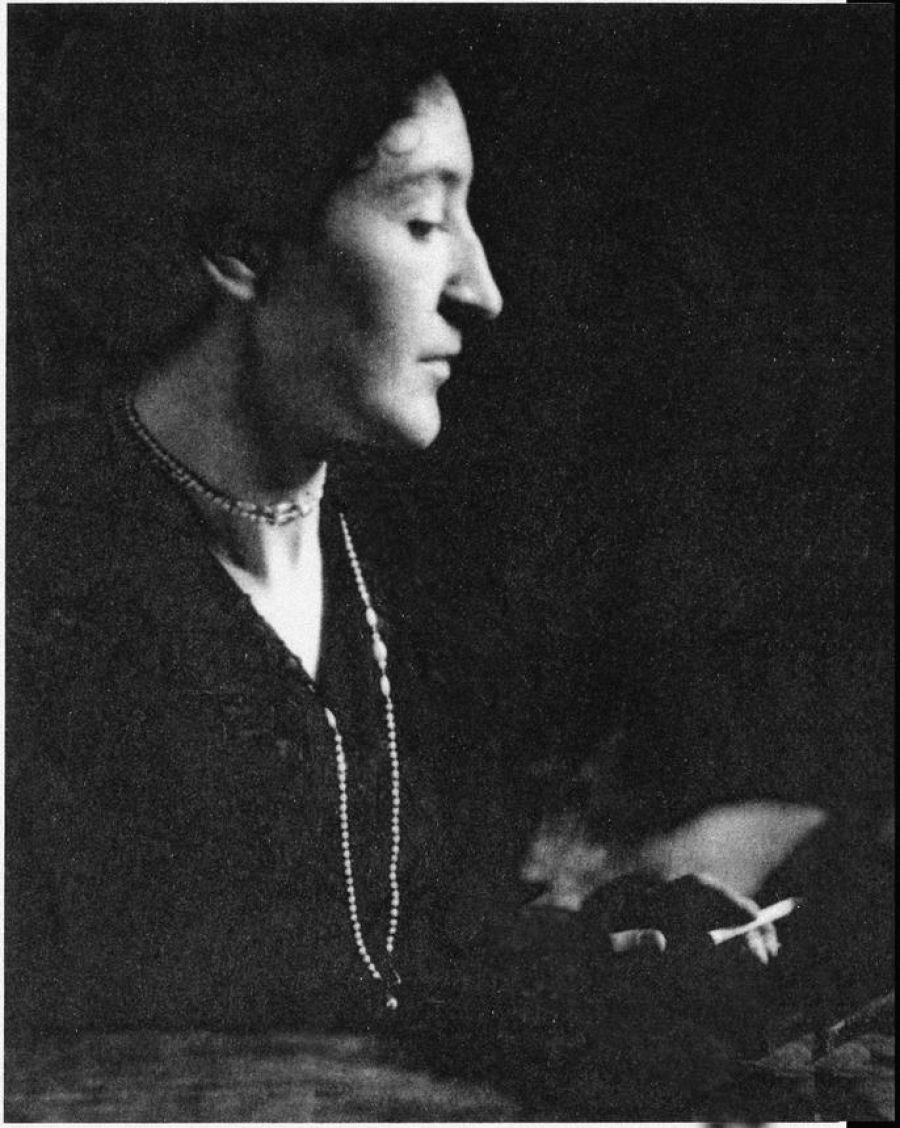

Richardson’s male pseudonym was the very condition that made her writing life possible. Back in 1914, when her French translator Paul Solanges had insisted on a photograph of the author whose work he was devotedly turning into French, she sent him one of the young Goethe, claiming a resemblance. She carefully slipped off her wedding ring whenever she was obliged to deal with journalists, as a means of protecting her private life – her ‘dormouse existence’ as she put it. She suffered interviews as ‘a ghastly business’, and when she reflected on the extent of her new fame, it was with more distaste than pleasure: ‘in one way, it has come too late. When I think of the joy it wld have been to me, 20 yrs ago. Now I’m cynical & blasé & too much turned inwards greatly to care. One can’t be neglected, as I’ve been, & not carry the mark of it somewhere. Well, the main thing is, I haven’t grown bitter over it – only indifferent.’ By mid 1931 all of her books were back in print on both sides of the Atlantic.

In Australia they still are, and now they are uncut.

A project to edit and publish new, complete and accurate editions of Henry Handel Richardson’s six novels, a novel translated from the Danish, her complete correspondence and her music – twelve volumes in all – began in 1998 with Maurice Guest (1908:1998) and concludes this year with the appearance of her great trilogy, The Fortunes of Richard Mahony (1917–29), which is published by Australian Scholarly Publishing. (3 vols, $140, 1740970985). The project is the work of Clive Probyn and Bruce Steele, of Monash University.

Comments powered by CComment