- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If Australian art has sometimes been perceived as wanting in style and opulence, recent art museum exhibitions and monographs examining the art and artists of the Edwardian era tell another story and reveal that there is abundant glamour in Australian art. The Edwardians (2004) and George W. Lambert Retrospective (2007) – both from the National Gallery of Australia – and Bertram Mackennal (Art Gallery of New South Wales, 2007) have succeeded in presenting Australian art in the grand manner from this most extravagant period.

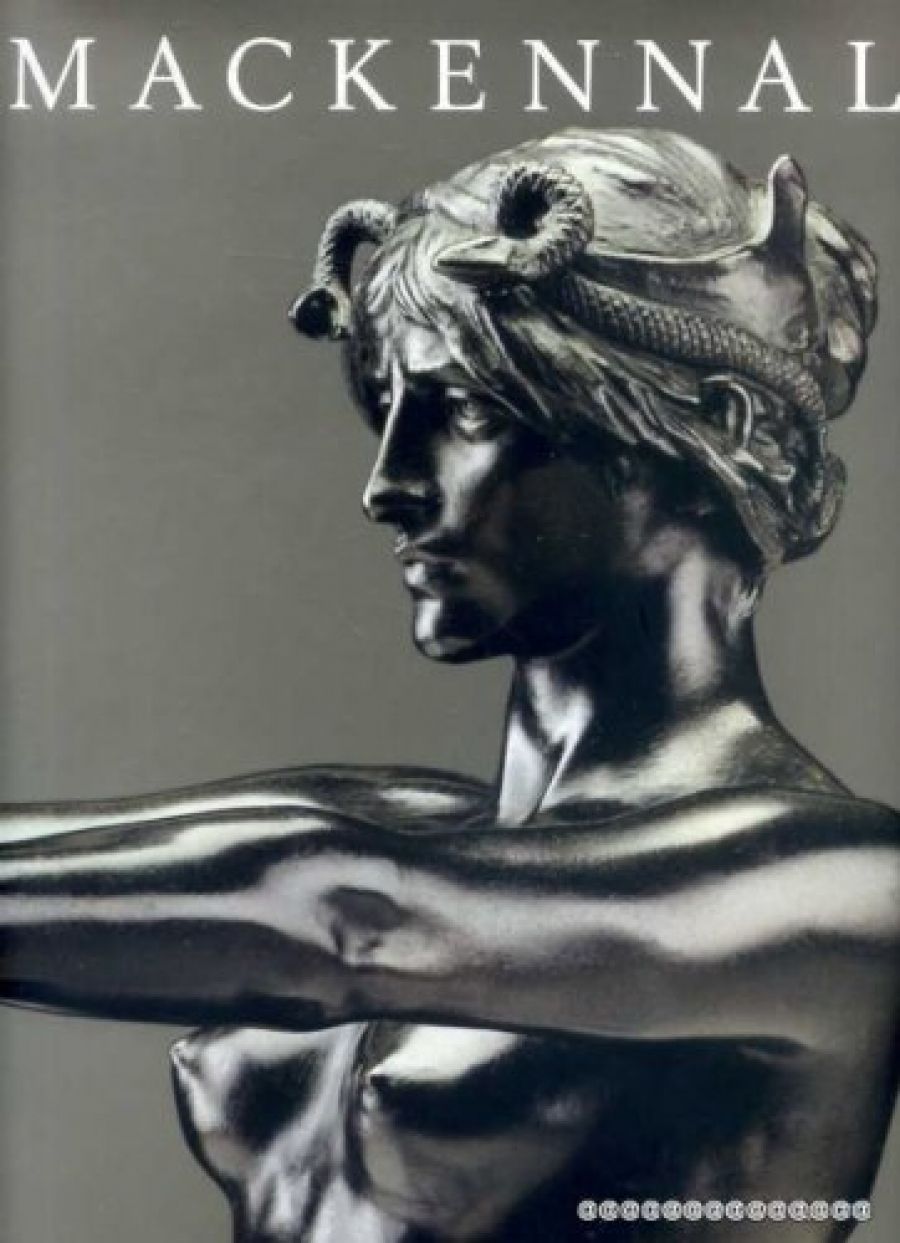

- Book 1 Title: Bertram Mackennal

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Fifth Balnaves Foundation Sculpture Project

- Book 1 Biblio: AGNSW, $80 hb, 216 pp, 9781741740110

Many Australians, even those familiar with his name, would be hard pressed to name more than one work by Bertram Mackennal. But remove his major public sculptures from view – Queen Victoria in Ballarat, King Edward VII memorials in Adelaide, Melbourne and Calcutta, The Shakespeare Memorial in Sydney, Phoebus driving the horse of the sun on the façade of Australia House, London – and the gaps would be obvious in their architectural or garden settings. Mackennal’s grand civic sculpture attests to his fame and achievements: he was the first Australian-born artist to be exhibited at the Royal Academy, to enter the Tate Gallery collection and to be knighted. But while he did not sink into oblivion after his death, his popularity is not up there with Lambert or Hans Heysen, let alone the Australian Impressionists.

Mackennal, born in Melbourne in 1863, was trained at the National Gallery of Victoria School. In 1882 he headed to Europe where he studied in London and Paris. His timing was perfect, for it coincided with reforms in sculpture in Paris and London, led by Auguste Rodin and Alfred Gilbert. Mackennal became part of the avant-garde in European sculpture. The status of sculpture was changing, as reflected in the social milieux in which the more ambitious sculptors moved. Mackennal made his name with a life-size bronze, Circe. Prominently exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1893, Circe gained an honourable mention and critical acclaim. Mackennal’s career did not flourish immediately: the National Gallery of Victoria hesitated until 1910 before purchasing Circe. Mackennal worked hard to obtain commissions during the 1890s. In this he was helped by his flattering portraits of the famous and the influential, such as Sarah Bernhardt (c.1892–93) and Melba (1899). Mackennal also designed the sculptures for the The Springthorpe memorial (1897–1901), Kew, Melbourne. This Gesamtkunstwerk – one of the finest, if not the best, examples of funerary art in Australia – conveyed the spirit of the New Sculpture in its setting and symbolism. It was the Edwardian love of such memorials to death, as well as statues of royal or other personages and the World War I memorials, that won Mackennal his public recognition. Such was his eminence that he designed coinage and stamps with the profile head of George V. On 12 October 1931 the king noted in his diary: ‘In the afternoon May & I … went to … see Mackennal’s medallion of dear Mama (which is not very good alas), he I regret to say died suddenly on Saturday.’

The long-awaited Bertram Mackennal – exhibition and book – are respectively curated and authored (with a team of contributors) by Deborah Edwards, Senior Curator of Australian Art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Edwards offers an exhaustive study of her subject, placing him in the artistic and social context of his day. She covers the wide range and quality of his work, while also giving critical appraisal. The result is a remarkable feat of scholarship and coherence, though the prose is not always mellifluous:

If the New Sculptors (whose statues of Victoria were sent across the Empire) maintained a generally distant relationship to such drives, nonetheless the faux-medievalising tendencies pervading much work of the 1890s (picked up by Mackennal in several war memorials in the new century) created a fictive transition zone with claims not so much to the temporal as to the national, in an invocation of the purported spiritual and chivalric qualities of British character.

Another complaint: page references to illustrations are not always given, which makes the visual arguments – central to such a publication and well articulated by Edwards – awkward to follow. But we are presented with a complex range of ideas on sculpture, on Mackennal’s relationship to late-nineteenth century French sculpture and on his connection with the New Sculpture movement in Britain. The other contributors provide insights into specific aspects of his work, and there is an arresting text on Mackennal as a designer of coins, medals and stamps, the least-known aspect of his art.

A CD-ROM attached to the inside back cover contains additional information and a catalogue raisonné of the artist’s work. This recent and welcome development in art museum publications provides invaluable source material which, for reasons of cost, would otherwise not be published and would thus remain in archives or curators’ files. We are warned that the CD-ROM is a work in progress, and that may explain the occasional typo. Nevertheless, it is a mine of fascinating and important information for our understanding of Mackennal and his oeuvre. Here you can find out detailed information on the whereabouts of multiple casts, the public commission and on provenances.

The exhibition, an elegant distillation of his finest moveable works, shows Mackennal’s originality to have been at its apogee in the 1890s. I saw it in Sydney, where the dark green walls complemented the sculptures in bronze, marble and gilt. Naturally, the numerous civic sculptures cannot be displayed in the gallery: this accentuates the importance of the monograph and CD-ROM. Both contain photographs of the public sculptures in situ, and works missing or no longer extant, as well as minor works not included in the exhibition.

The Art Gallery of New South Wales is to be congratulated on devoting the resources to produce such a splendid and beautifully illustrated volume on one of Australia’s most important sculptors. It will remain the standard reference for years to come. The exhibition, not to be missed, is showing at the Art Gallery of New South Wales until November 4, and then at the National Gallery of Victoria, from 30 November 2007 to 24 February 2008.

Comments powered by CComment