- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Pamela Bone has written a remarkably brave book. She writes about how the chemotherapy which she underwent after the diagnosis of multiple myeloma in 2004 robbed her of the fearlessness of her life as journalist, human rights activist, feminist, and public speaker. She pays tribute to the late British journalist John Diamond, who insisted that writing about his cancer was not brave at all. Bone disagrees: ‘I think he was very brave. And although he is dead, his voice, with its decency and wit, speaks to me from the pages of his book.’ Bravery, decency and wit are among many words that could equally be used to characterise Bones’s own voice, which mercifully is still strong, always profoundly intelligent and humane as she addresses the big questions of death and dying, poverty and injustice, all the while paying tribute to the love of family and friends, the dedicated and good-humoured care of health professionals, and the kindness of strangers.

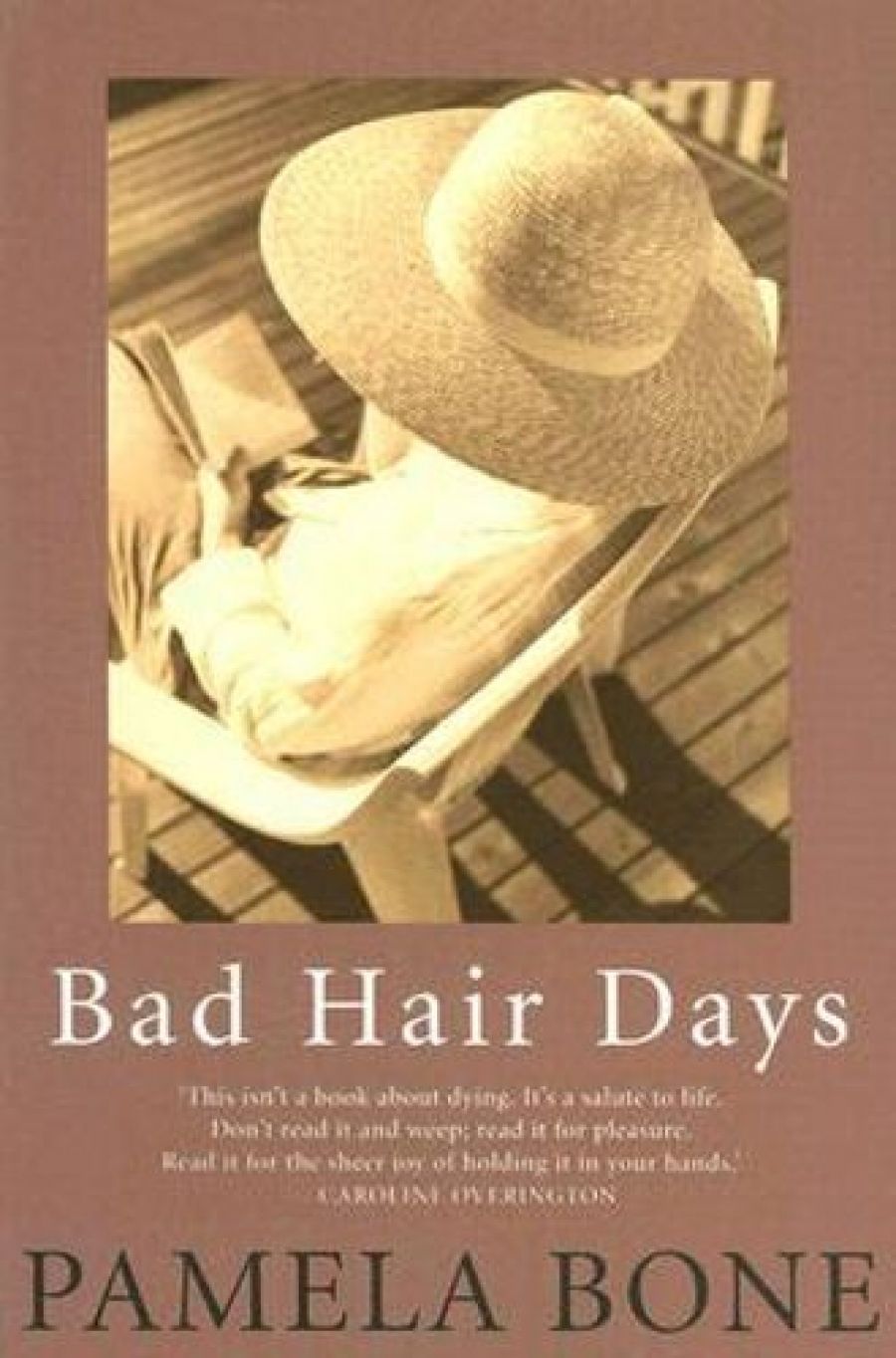

- Book 1 Title: Bad Hair Days

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $32.95 pb, 226 pp, 9780522853698

Her book began as one about the experience of cancer and its treatment, but it ended as something different, a work which explores the relationship between the body of a woman with a serious form of cancer and the body politic in its national and international manifestations. Bad Hair Days is not a textbook for cancer sufferers, but it speaks resonantly to and for cancer sufferers about the power of illness and its treatment to disenfranchise them – to transport them from what Bone calls citizenship of the world of normality to a numb and strange place which receives intermittent signals from the normal world.

As many as one in three Australians develop some form of cancer, and nearly all of us are, or will be, secondary sufferers, through the illness and deaths of parents, lovers, children and friends. For all the wise and provocative things this book has to say about the sorry state of global politics, feminism’s need for re-energisation, and addled thinking at home about ethical issues such as stem-cell research, its enduring value is to speak to and for those whose lives are shadowed by cancer. Losing one’s voice, sometimes literally, nearly always metaphorically, is an all too common experience for the citizens of Cancer Country.

One of the late Susan Sontag’s legacies was her Illness as Metaphor (1978), which takes to task the language commonly used to speak of serious illnesses such as tuberculosis and cancer. But so instinctively primitive are our responses to the attack from within that even people who should know better fall into the lexicon of battle (fighting, victory, defeat, the enemy) when they talk about disease, sometimes their own, but more often that of someone they love. I remember my own unvoiced rage when well-meaning friends told my wife in her dying days of the triumphant fighters against cancer they had known (He/she beat it!). What I saw as massive insensitivity my partner, wiser than I, recognised as the language of an unspeakable fear (‘They haven’t been here,’ she said once, smiling.) I remember, too, her using Pamela Bones’s exact words, ‘Where cancer’s concerned, I am a pacifist.’

Let all of us think twice about exhorting a seriously ill person to ‘think positively’. To do so is to subscribe to a bizarre presumption that we are somehow responsible for the mysterious engines that are our bodies, and complicit in their mechanical failures. Ian Gawler, survivor par excellence and a source of inspiration to many, deserves Bones’s castigation for his daffy and offensive remarks about the cancer-prone personality.

To say, as Bone does, I had a strong will to die (after being battered by an arsenal of drugs and surgical procedures) is a mark of devastating honesty. She acknowledges that she is in the fortunate position of having the knowledge of the means to end her life should she choose to. But her wish is not to do that, unless cancer affects her to the point where she faces the prospect of mindless identity, hence no identity at all. This will be a familiar experience to many other people visited by terminal illness.

It is entirely understandable that Bone should have instinctively avoided any attempt at a writing cure for cancer when she was first able to return to limited professional work; it was crucial to her psychic health that she be able to look outwards to the public world of tsunamis and human-engineered disasters abroad, the victimisation of women and domestic bloody-mindedness that have for thirty years been the stuff of her professional career. She is too hard on herself when she observes, ‘I think I might have done readers more of a service by writing about my illness.’

Readers of her opinion columns in the Age will do well to pay close attention to Bones’s defence of her support for the invasion of Iraq, based on her work with refugees who had escaped Hussein’s horrors: ‘I supported that war. Of course I did. Saddam Hussein was cutting women’s heads off … The question I need to answer is whether, if I had known the outcome, I would have supported it. The answer is no. I would not …’ I suspect that Bone may be more understanding than I am towards the anonymous Islamic writer I turned up on a Google search: ‘Perhaps this is a sign from God to Pamela [sic] ... the irony is that she’s got a cancer of the bone. It’s not funny, I know. But it’s probably a sign. Sadly she hasn’t seemed to figure it out.’ Probably? Not funny, but maybe there is hope for this clumsy ironist, and for the legions of Christian fundamentalists who share his sadly uninformed views. The anger of Bad Hair Days is directed at the old enemies injustice, corruption and greed, rather than at any enemy within. Opinion writers do not often get the last word, but Pamela Bone deserves hers, at least for this book:

Some time ago I read a piece of advice for people who have incurable cancer. It seemed at once very simple and very profound. It said: yes, you are going to die, but until you do, you are alive.

Comments powered by CComment