- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This impressive volume surpasses most assumptions about the scope, depth and eloquence of an exhibition catalogue. Curator and editor Terence Lane has gathered together thirteen of Australia’s leading art historians, historians and curators, all recognised experts in their fields.

- Book 1 Title: Australian Impressionism

- Book 1 Biblio: NGV, $79.95 hb, 352 pp, 9780724102822

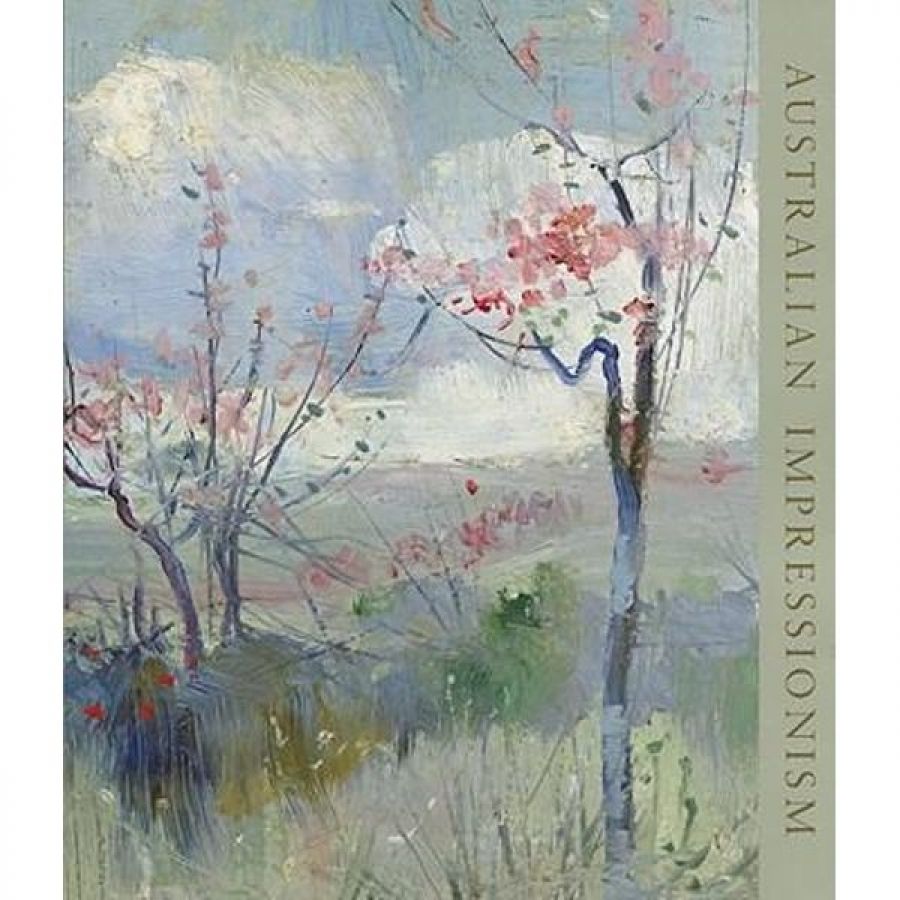

The cover presents a seductive detail from Charles Conder’s Herrick’s blossoms (c.1888), a white and pastel blue flurry of brushwork, spotted with confetti flecks of pink and cherry, and traversed by spindly black boughs. Intimate in scope, japoniste in its aesthetics and English in its concept of transience, inspired by the poet Robert Herrick, the work is in bold contrast to that chosen for the cover of its illustrious predecessor, the Golden Summers: Heidelberg and Beyond exhibition of 1985, edited by Jane Clark and Bridget Whitelaw. Arthur Streeton’s Golden Summer (1889) represents a more heroic poetic idea, captured in the burst of radiant light on the hay-yellow paddock, with figures working to move the sheep towards the homestead against a majestic backdrop of distant hills. Yet, despite its enthusiasm for the ‘Heidelberg’ vision, Golden Summers had already, with sustained attention to primary sources, unpacked the mythic image of the Australian bush, revealing it as an invention of city dwellers that expressed their fantasies as much as their observations.

A major achievement of this catalogue is to consolidate and extend the work of Golden Summers by placing Australian Impressionism in a wider context, going beyond Heidelberg to Box Hill, Mentone, Sydney and the Hawkesbury, from male painters to female, from visual artists to musicians, the literati and poets, from untouched nature to the urban experience. Above all, Impressionism in Australia was vitally connected with developments in Paris, London and European regional locales. It is the emphasis on this global avant-garde context that distinguishes this catalogue from the earlier one and explains the sophisticated Conder cover. The exhibition title critiques the picturesque but narrow term, the ‘Heidelberg school’, and replaces it, as Gerard Vaughan explains, not with the well-known French Impressionism of Monet, Pissarro or Manet, but with plein-air naturalism, a movement which grew out of eighteenth-century academic sketching practice and was applied in quite diverse ways by artists such as Corot, Carolus-Duran, Whistler and Bastien-Lepage.

Australian Impressionism is not, then, a naïve translation of visual experience into pictorial reality. As powerful as the works might be in evoking hot, crackling days in the bush or dusty afternoons in the city, their iconic resonance depends on more than a new perception of geographical location. The catalogue sharpens our understanding with an array of cultural influences. Writing with measured passion, Daniel Thomas reveals Tom Roberts’s Sunny South (1887) as a Mediterranean pastoral idyll with mythic sources and symbolist potentials. Humphrey McQueen demonstrates the importance of the Spanish old masters for Roberts, while also indicating the complexity of such influences when he suggests that his depiction of A Spanish beauty (1883–84) is in fact an English woman in fancy dress. Leigh Astbury unpeels numerous layers of nationalism, nostalgia and nature worship in the motivations of Roberts, Streeton and Fred McCubbin. With lively references to their media impact, David Hansen argues that the ‘deliberate iconicity’ of their works was created through an emphasis on working rural life, with sources in the ‘landscapes of labour’ of provincial France and countryside Britain.

Yet these parallels cannot override the importance of specific locales. With characteristic attention to detail, Daniel Thomas and Mary Eagle point to the grains of sand stuck in the facture of Conder’s Holiday at Mentone (1888) and Roberts’s Holiday sketch at Coogee (1888). In the first of two contributions, Eagle pursues the theme of artistic influence in depictions of Coogee by Roberts and Conder. Her sober analysis of ‘the painters’ working method’ contrasts with the realm of ideas allowed into her second essay, in which she writes of Streeton’s sexualisation of the sea in his depictions of Sydney Harbour, and its role in prefiguring Sydney’s cult of the surf. While she may be justified in emphasising Streeton’s avoidance of individual emotions, her claims that his work (inspired by Schopenhauer’s critique of human will) allows for no subjective feelings overlooks the emotional aspirations he invested in landscape, the kind of hymn to nature’s energy and integration indicated in the title The Purple Noon’s Transparent Might (1896), a line drawn from Shelley. Jane Clark, however, comments on the special emotional significance of rivers for Australian artists in her account of the way this painting came into being. She captures Streeton’s intoxication when he discovered what Lionel Lindsay called ‘that wide field’ – the view of the Hawkesbury River from the terrace at Richmond – while also pointing out that the bold square format of the canvas, which so intensifies the viewer’s sense of proximity to the expansive scene, derives from the latest international aesthetic practices.

There can be no doubt that the strength of these essays is in their imaginative historical research. Illuminating detail abounds in, for example, Ann Galbally’s account of Conder’s early life as a surveyor and Andrew Brown-May’s vibrant evocation of Melbourne life, which enables him, for example, to explain the presence of a goat in McCubbin’s Melbourne Gaol in sunlight (1884) or to identify the poignant figure of a bootblack in Roberts’s Allegro con brio, Bourke St West (1885–90) as one Charles Day. In three meticulously researched essays, Terence Lane gathers letters, press previews, catalogue entries and Table Talk commentaries, enabling intimate exposure to the artists’ experience of painting together in nature, to the extravagant Grosvenor Chambers studios, which would be the envy of any Flinders Lane artist today, and to the poised, confident and ‘stage managed’ promotion of the 9 x 5 exhibition. In a fascinating and original analysis, Angus Trumble documents the two-way flow of influence between Australian portraiture and its British counterpart, underpinned by the strong ties between key British portrait painters such as Millais and Watts and Australian society and artists.

A major contribution of the catalogue is to recognise the centrality of allegory and symbol in Australian Impressionism. As Ted Gott reveals, Charles Conder preferred his bizarre allegory Hot wind (1889) to the much-lauded drizzling rain clouds of Departure of the Orient-Circular Quay (1888). While the general public’s devotion to a mimetic model of Australian Impressionism is understandable, Gott produces a range of evidence for other more conceptual and literary interpretations, citing, for example, Roberts’s admiration for Puvis de Chavannes, or Conder’s regard for Robert Browning.

Given the complexity and subtlety that is a hallmark of these essays, then, one might question the concentration on big-name artists and hope that future exhibitions might explore those lesser known. The major concession, of course, is the inclusion of Jane Sutherland. Frances Lindsay persuasively argues for her status and the sheer radicalism of her depiction of The harvest field (c.1897). Soft, blowsy and chromatically given to purple, her strangely elusive works make new claims on the viewer accustomed to the crisp clarity of her male colleagues.

These writers represent a large part of a ‘who’s who’ in Australian art history. It is notable, then, that it is the roll-call of an older generation, and that most hail from the Fine Arts Department, University of Melbourne. Where are the younger scholars and the alternative psychoanalytic, literary, philosophical and political perspectives? This is not an edgy catalogue, but safe and sound. All contributors agree on methodology: that is, history based on primary documents. While this produces much new material that importantly readjusts our view of the works, it is only occasionally driven by the view, which surely the Impressionists espoused, that art is at the centre of debate about the good life. This catalogue is sure to attain the status of a classic: a generous, superbly written resource for many future generations. Yet we may worry about where those generations will come from. At a time of the recent closure of two Melbourne art history departments and the absorption of the University of Melbourne’s department into the School of Culture and Communication, it can only be hoped that we don’t all succumb to the transient fate symbolised by Conder’s blossom trees that so elegantly grace its cover.

Comments powered by CComment