- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Against The Grain celebrates two iconoclastic Australian historians: Manning Clark and Brian Fitzpatrick. Comprising papers from a 2006 conference organised by two of their daughters, both distinguished academics, Against the Grain offers critical thoughts and reminiscences of family members, friends, colleagues, students and academic successors of the two men.

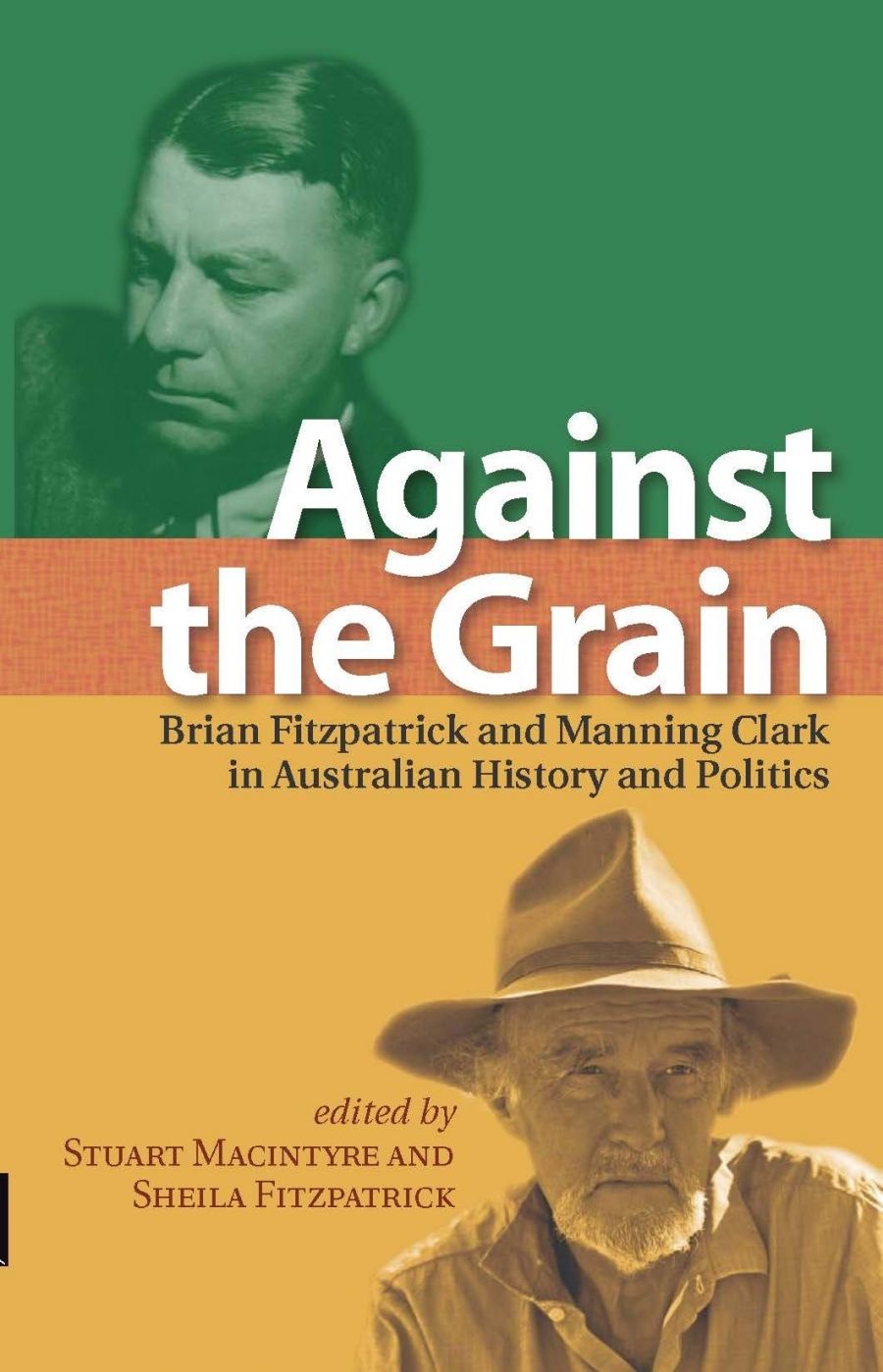

- Book 1 Title: Against the Grain

- Book 1 Subtitle: Brian Fitzpatrick and Manning Clark in Australian history and politics

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $49.95 pb, 279 pp

Although they share the pages of this book and enjoyed, for a time, a warm friendship, Against the Grain performs different functions for Clark and Fitzpatrick. For the right, the former typifies all that is wrong in the study of Australian history, politics and society. Fitzpatrick, by contrast, is an obscure figure; his work and his political leadership in the civil rights struggles of the early to mid-twentieth century are scarcely remembered. But, as Stuart Macintyre notes, Fitzpatrick’s posthumous obscurity has perhaps been to his benefit. The ‘culture wars’ in the Howard era have not been kind to the shade of Manning Clark; contrary to the popular aphorism, lack of publicity can trump unflattering notices.

It is ironic that Clark is so reviled as a Leninist distorter of the national story, for he was once admired by conservatives for breaking with labour historians and dismissing the notion that the labour movement established Australia’s national character. But when he argued that the nation was defined by race, riven by sectarian conflict and had struggled to absorb the Enlightenment, Clark forfeited the support of those who preferred to see the march of Australian history as one of progress. Fitzpatrick, too, never sat comfortably with labour historians, let alone the Establishment. His interests were unmodishly broad, his work equally expansive: he wrote economic, labour and imperial history. As Ann Curthoys observes, his ideas have fallen foul of fashion; he did not focus enough on Australian affairs for the liking of economic historians and overstated, in the judgment of labour historians, the importance of British trends for Australia.

Both men were uncomfortable with orthodoxy of any stripe, but it is important to understand why Clark’s work lives on while Fitzpatrick’s does not. Macintyre supplies an explanation, styling Fitzpatrick and Clark, respectively, as ‘the radical and the mystic’.

The ‘radical’ led the more varied professional life, practising journalism, participating in radical politics and co-founding the Australian Council for Civil Liberties in 1935. As an historian, he investigated the formation of Australian capitalism, conducting exhaustive and innovative empirical research. However, after subsequent writing on the Australian labour movement, he struggled to hold down academic positions, and his work became increasingly inconsistent. Personal problems – divorce, booze, melancholia, hard living – began to fetter his output. His eclecticism and lack of discipline compounded people’s doubts about his personal respectability, costing him professional opportunities.

Clark was also conspicuous for eschewing secular, objective history. For him the ideal historian was both a fox and a hedgehog, one who ‘pondered deeply over the problems of life and death’ but who knew ‘one thing – and [felt] it deeply’. Clark’s disillusionment with the dominant national myths, as he saw it, of Australian history, and his belief that humanity ‘was afflicted by dark and powerful forces’, indubitably reflected the sense of professional frustration and betrayal that he felt during the Cold War. He was subjected to adverse ASIO security checks, ongoing surveillance and the revocation of professional opportunities. Fitzpatrick, too, was the target of ASIO surveillance, although it is difficult to determine the effect this had on his career.

But if ASIO did not appreciate Clark’s work, thousands of Australians were inspired by the ‘mystic’s’ conception of the human struggle and by the striking way that, in his epic national history, he shaped Australia’s history around this struggle. His appeal also lay, several contributors aver, in his wonderful capacities as a storyteller. These capacities, Mark McKenna notes, could make Clark an unreliable practitioner of the routine dimensions of history, but they elevated his source material into the realm of his readers’ lived experience.

Sheila Fitzpatrick and Katerina Clark explain how their fathers’ personal characteristics shaped their work. Fitzpatrick writes affectingly of a childhood spent with a father whose strength of personality and intellect won the loyalty of his family. Never embarrassed by her father, Sheila absorbed his advice to defend one’s convictions in the face of public pressure. At university, he became an asset, a minor icon. Then, just when she might have got to know him as an adult, he sent her abroad to seek her fortunes away from narrow, Cold War Australia, and died.

Katerina Clark opts for a less personal memoir, but defends her father’s intellectual integrity through her intimate knowledge of his passions and foibles, discrediting claims that he was a communist stooge. Certainly, Manning was fascinated by Russia and its writers, none more than Dostoevsky, whose ‘critique of the rational and the materialist’ greatly appealed; but he was no communist, or capitalist, or Catholic. He could practice ‘casuistry’, as he did overlooking Dostoevsky’s bigotry and conservatism, but he was too ‘ecumenical’ and individualistic to place all his ideological eggs in one basket. And his command of the Russian tongue rendered him useless to any Soviet keen to cultivate his service.

Inevitably, Against the Grain is eclectic. It has no single tone or strong editorial voice, but its purpose is to restore the reputation of neglected and vilified contributors to Australian society, and to remind us of the diversity and fervour of our intellectual and political heritage, as Australia dozes through its own version of Brezhnev’s Big Sleep.

Comments powered by CComment