- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Michelle de Kretser’s third novel opens with a man and a dog in the Australian bush, an image whose hooks are sunk deep in our national psyche. Recall the Edenic first chapter of The Tree of Man (1955), with its portrait of Stan Parker settling on a patch of virgin wilderness with only his dog for company. In the Australian Garden, Eve is a subsidiary companion.

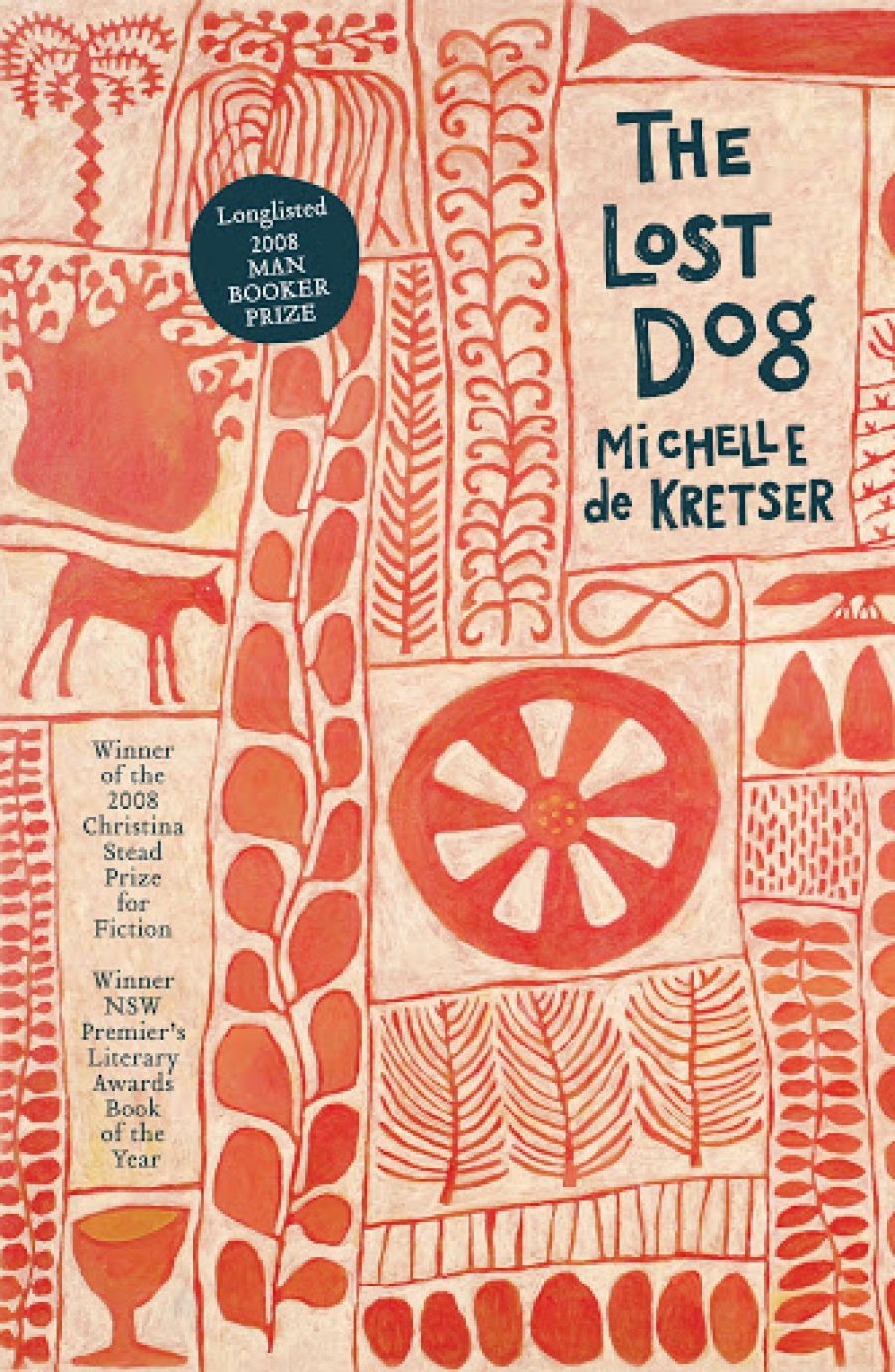

- Book 1 Title: The Lost Dog

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $35 hb, 354 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/M0L0J

By the time the dog disappears, these differences have already been roughly sketched. And although the idea of vanishing into the bush is another old Australian trope, it is given a fresh twist by Tom’s complex sense of remove. The implication here is not only that the dog has suddenly absented itself but also that Tom lacks the perceptual orientation – the local ‘ways of seeing’ – to find him again.

De Kretser knows full well that the loss of a dog is a frail hook to hang a novel on. There is an intentional descriptive sparseness (the dog lacks a name or a breed) brought to this simple set-up; one that unfolds, nonetheless, in a breathy and portentous manner. Like all good ghost stories – think of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw (1898) – just enough space is made within a plausible realism for ambiguity. And ambiguity, the great Jamesian subject, is what The Lost Dog is all about. The owner of the shack is Nelly Zhang, a Chinese-Australian artist of no small repute and some large notoriety. Her husband, Felix Atwood, was a wealthy financier who disappeared under mysterious circumstances from a beach near the country place some years before. Although circumstances pointed to suicide (Felix was about to be revealed as a rogue trader), a woman was also sighted leaving the beach that day. That Nelly painted an eerie series of canvasses referring to these events soon after only added to the scandalous consensus that she was somehow involved.

Tom knows nothing of Nelly’s past when they first meet, however. He is drawn, first and foremost, to the shockingly straightforward beauty of her art. Only as a relationship develops between the two – and even then only partially, incrementally – does he learn of the ‘contaminated glamour’ of her background. Tom embraces the bohemian circle surrounding Nelly with the relief of a man recovering from a failed marriage, as well as the naïve fascination of one still in flight from a youth of poverty and ugliness. But like the mild, thoughtful Lambert Strether of Henry James’s late novel The Ambassadors (1903), Tom is drawn toward this aesthetically richer world without fully understanding its underlying currents. He remains uncertain of the degree to which its charming denizens are divorced from the ethical realm.

This uncertainty extends beyond the twists and turns of narrative, or any Jamesian investigation of character. Tom may have an untutored response to obsolete categories such as ‘beauty’, but his academic’s impulse is to reduce images to signs, and to submit those signs to semiotic scrutiny. For Tom, the unmediated life is not worth living. And during a series of intermittent trips back to the country in search of his dog, much of his thought is given over to meditations on place, modernity and the function and value of art.

For all the brio Tom brings to these subjects – whether they be Kunderan aperçus on the nature of Kitsch, or Sebaldian meditations on non-places and the fabric of the urban – The Lost Dog doesn’t quite get its balance right. Kundera and Sebald, for instance, are poets of intellect. In their creative efforts, narrative form is refracted though philosophical critique. So it is that traditional genre models tend to break down in their writing. Fiction and reality, the voice of author and narrator, essayistic and narrative modes are elided, allowing the lyrical and the critical to coexist. Here, by contrast, Tom’s insights are laid, stencil-like, over a traditional fiction. What readers are asked to accept here is a literary artefact that simultaneously proclaims a philosophical pessimism about literature – a realist novel whose narrator defines realism as merely the ‘effect produced by the accrual of detail’ to create ‘elaborate scenarios that mimic the solidity of truth.’

The Lost Dog is, despite this complaint, a richly complicated book, in which the author seeks to recast Henry James’ ambiguity, his dramas of irresolution, in postmodern terms. Where James explored the enigma of character, de Kretser explores the equally enigmatic categories of ethnicity, sexuality, gender; and where James used ghosts, ‘vastations’ and the uncanny in its older sense, de Kretser employs Freud’s and Heidegger’s notion of unheimlich – our unhomedness in the world – to illuminate that sense of vertigo induced by modernity.

The Lost Dog’s prose can be overheated on occasion, and the voice of its semi-Indian narrator may be off-putting in its Brahminical severity, but the novel’s intelligence and (like Nelly Zhang’s artist’s eye) its ‘tremendous capacity for appreciating the world’s detail’ more than outweigh its flaws.

Comments powered by CComment