- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Gay Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I recently watched a DVD of The Big Chill (1983). The film’s melancholy over the lost radicalism of the 1960s pervades What Happened to Gay Life?, Robert Reynolds’s new book. One might guess that a book about gay – once synonymous with happy – life might feature a bit of glitter and laughter, but this is not the book’s point.

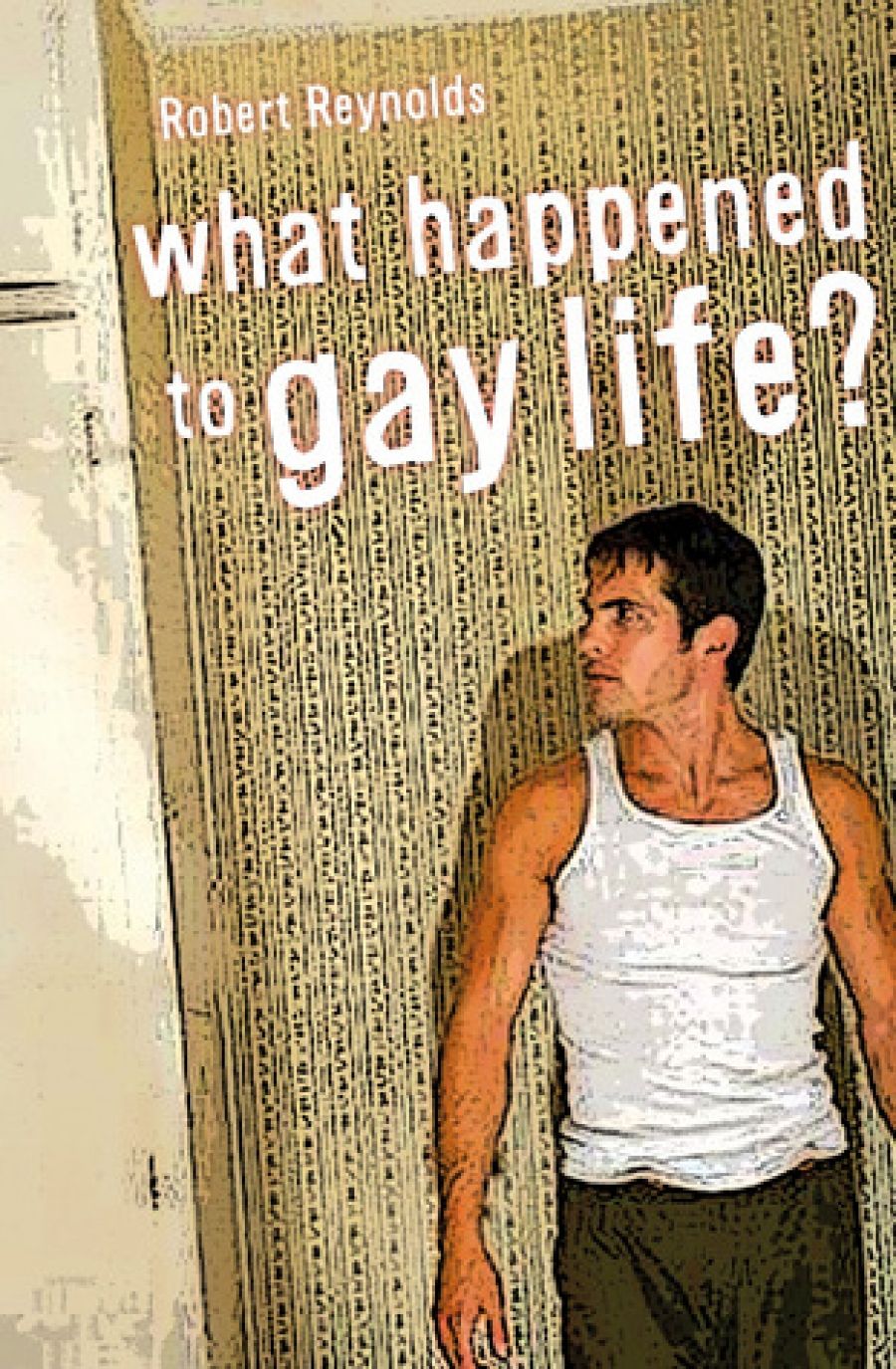

- Book 1 Title: What Happened To Gay Life?' by Robert Reynolds

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $29.95 pb, 224 pp

Through the narratives of ten gay men in Sydney, Reynolds recounts a social history of the development of a gay subculture, its early ‘golden years’, its shift towards the mainstream and its ‘modernisation’. It is an approach that is rich in detail and subject matter, moving easily through a range of questions about what it means to be a gay man and what it means to be human: how family does or does not shape us; the role of love, sex and relationships in our lives; how we create communities; our identities, selfimage and friendships.

Reynolds’s is an intelligent and engaging voice, and his setting of gay history within a larger Australian political context brings further depth to the text. However, he is too forceful a guide for my taste: the delineation of each man as a case study (his parents’ political views, his timidity or confidence, his height or weight) can be too neat; I worry that their agency and the authenticity of their voices are dampened not only by the frame of their psychological portrait but also by the labels given to them: reformer, mainstreamer, radical, individualist.

The first part of the book belongs to elder statesmen such as Ken Davis and Paul Van Reyk, whose histories are traced from their sexual awakenings to their current reflections on the gay community. We read about gay lives that were consumed with activism and idealism, an insular world where sexual or romantic quests combined with rallies and meetings. These men lived and breathed a politics of hope. Even more pronounced than that of other 1960s radicals, the gay liberationist’s dream was that different sexual mores and new life choices would transform the world.

Clearly, Reynolds is sympathetic to this viewpoint. But while we can lament the failure to unite gay, environmental, feminist and other social justice causes into a vibrant, progressive social movement, we might also celebrate the victories of rights-based approaches that resulted (albeit not in Australia) in triumphs such as gay marriage in Canada.

The author’s rose-tinted vision of the past is also evident when interviewees are not vouchsafed the same joy in their connections with the gay community as their elders: one because his experience of gay life ‘has been drained of politics and broad social bonds’; another because the excitement at his freedom is ‘not substantially different from … many individuals in a cosmopolitan, childless, globalised world’.

After the radicals comes a gay identity that is not as separate from the mainstream. Anthony Schembri’s work with the Gay Lesbian Rights Lobby required quiet diplomacy with high-level government contacts. Alan Graves’s career began in gay community politics but led to a job in Macquarie Street. A trio of younger interviewees then unveils a further level of integration with society, mixing with straight and gay friends, rarely visiting gay bars and supporting Mardi Gras but with little investment.

Reynolds, curmudgeonly at times, pokes fun at himself (about ‘emo’ culture he says, ‘I was born 20 years too soon’). Unambiguous is his dislike of gay Sydney: its narcissism, its shallowness. But when I arrived in Sydney in 1999 from Canada by way of London, gay Sydney was dazzling. This was a time when Mardi Gras represented diversity and acceptance, when gays and lesbians brought straight parents, siblings, friends and neighbours along to the party. Rather than a time that ‘demanded too much of sexual identity’, it was simply a moment in history, much like the radical 1960s, which could not be sustained.

At a personal level, my touchiness about some of Reynolds’s views may attest to their accuracy. I have gone from being fully involved in Sydney’s gay community – choir, sports teams, dance parties, a seat on the board that saw the collapse of Mardi Gras – to mostly wanting to watch DVDs with my boyfriend and tend my succulents. What happened to gay life indeed?

Nevertheless, Reynolds’s history of Sydney’s gay life, community and identity is incomplete because of the subjectivity of the author and the limitations of telling a complex history through a handful of individual stories. Rather than a fault, I consider this an invitation, more precisely a dinner invitation to sup with eclectic, intelligent guests, away from the loud music of bars or a dance party. A critic’s role may be negative in order to point towards the positive: in this case, lives made richer but not controlled by gay identity and community. Observers of or participants in Sydney’s gay life will be challenged to consider how their experience fits in with those of the others at the table, as the host, with a sad but wry grin, suggests, ‘let us discuss where we’ve been’.

Comments powered by CComment