- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Howard's army

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

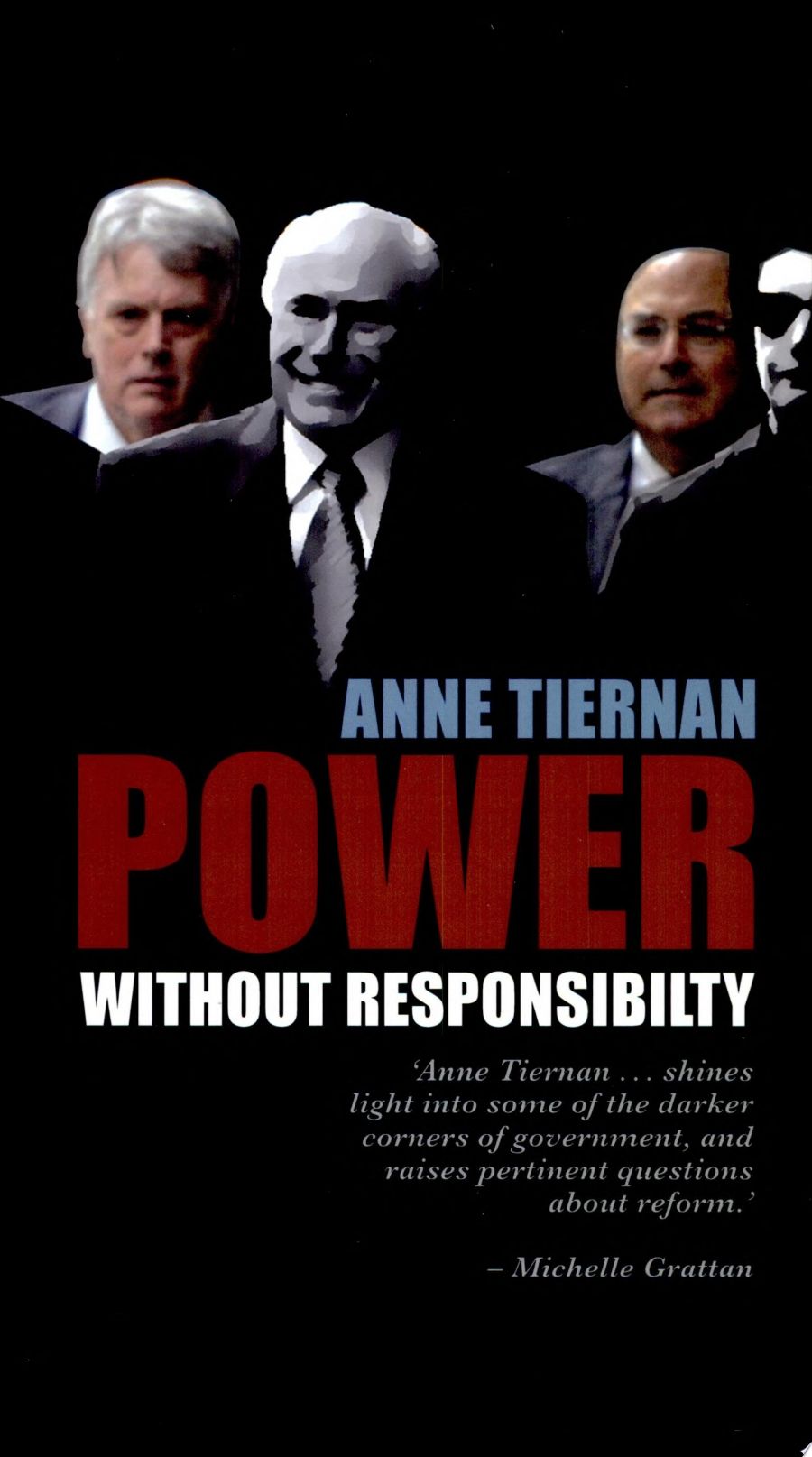

The cover says it all. The photograph comes from the Cole Inquiry, but it could be from any number of recent events. In the centre is Prime Minister John Howard, smiling without hubris, a confident leader going about the business of leadership, ready to inform the Cole Inquiry what he knew and what he was never officially told. But the prime minister is not alone. Blacked out on either side are two of his security detail: ‘fit for office’ does not begin to describe the appearance of lean efficiency of this pair of male and female minders. Just behind them are two classic minders, both more than a little tense but featured in bold colour, one with eyes up as if anticipating the show of prime ministerial confidence; the other with eyes lowered, anticipating what might go wrong. Not that it does.

- Book 1 Title: Power Without Responsibility?

- Book 1 Subtitle: Ministerial staffers in Australian governments from Whitlam to Howard

- Book 1 Biblio: UNSW Press, $34.95 pb, 283 pp

We learn from Tiernan’s opening chapter that the lowered eyes belong to the prime minister’s media minder, Tony O’Leary, whom Howard has employed for two decades. The other eyes belong to Arthur Sinodinus, who was, until recently, Howard’s ‘chief of staff’, to use an American term that Tiernan notes is now commonplace, reflecting a larger story about the entrenched transfer to Australia of American modes of governing. Both minders have been on Howard’s staff since Opposition; both helped Howard to win the 1996 election; both have helped manage the Howard régime. At a personal level, Tiernan’s book records not simply the extensiveness of Howard’s unprecedented numbers of minders but also the remarkable endurance of what we might call the Howard ‘minder set’. Howard’s critics would do well to ponder the willingness of so many minders to serve and remain serving this distinctive prime minister.

Lesson number one is that the Howard team are stayers. Lesson number two is that the Howard team is large, reflecting steady growth in numbers over the decade of Howard’s government – from 294 to 445. This number includes the ministerial staff serving all ministers, not simply the prime minister. The executive branch of government has sprouted new tendrils, so much so that the tree of government no longer looks like the one in the traditional textbooks. During parliamentary sessions, nearly all minders work in Parliament House, where they vastly outnumber the elected members. One of Tiernan’s themes is that the Howard government now represents a new system of Australian national governance, which operates through something resembling a White House model of executive power.

When Labor last governed, the appropriate model was illustrated through the British television series Yes, Minister and its successor, Yes, Prime Minister. Not any more. The decisive change is not that the right wing has replaced the left wing but that West Wing has replaced Yes, Minister as the morality play for minders. One innovative feature of Tiernan’s analysis of Australian politics is her use of American political science frameworks to help explain this dynamic, which she suspects is present at state as well as national level. I cannot think of another recent book on Australian politics that draws so constructively on United States scholarship on executive government to clarify the changing nature of executive power in Australia. The frequent reference to American political science literature is itself a major signal of what Rudd might term ‘a fork in the road’ of the study and practice of Australian government.

Speaking of Rudd, one suspects that, whereas Labor traditionalists shared with conservatives a sense of pride in the professional ethos of public service mandarins, Labor envies Howard his consolidation of bureaucratic executive power over and above the public service. Certainly, the Howard government did not start this executive trend. Blame Gough Whitlam, if you must, for setting us off in this direction, emulating Canada under then Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. But remember that Whitlam never approached Paul Keating’s record of more than 350 minders.

In government it helps to have help. Parliamentary secretaries can have up to five minders, junior ministers can have up to eleven, and cabinet ministers can have up to nineteen. Tiernan’s argument is that the army of ministerial minders are all, in effect, Howard’s handmaidens and henchmen, because their employment is ultimately controlled by the prime minister. This is certainly the case for the many now employed in central services such as the ‘cabinet policy unit’ and the ‘government members secretariat’, but it is also true for those working as support staff to ministers, who are themselves appointed at the prime minister’s pleasure. Howard’s personal office has forty-seven persons hired and potentially fired by the prime minister, not including non-advisory officials allocated to security and transport. In contrast to Howard’s army of 445, the number in the United Kingdom is less than eighty. Canada, so close to the United States, comes in at about 200, and New Zealand does credible service with just over fifty. Tiernan notes how Australia is also distinguished by the absence of external regulation or public accountability of minders. Westminster the Howard model ain’t.

Minders matter, especially in media management. Michelle Grattan notes that media minders are at the centre of the new enterprise of controlled communication. Tiernan describes Howard as ‘the most media-active prime minister Australia has even seen’. Power without Responsibility draws on extensive interviews with those ‘in the know’, and recounts the role of minders in managing an increasingly responsive public service. Tiernan’s final reform chapter is a must-read before the coming election.

Comments powered by CComment