- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Act of instability

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

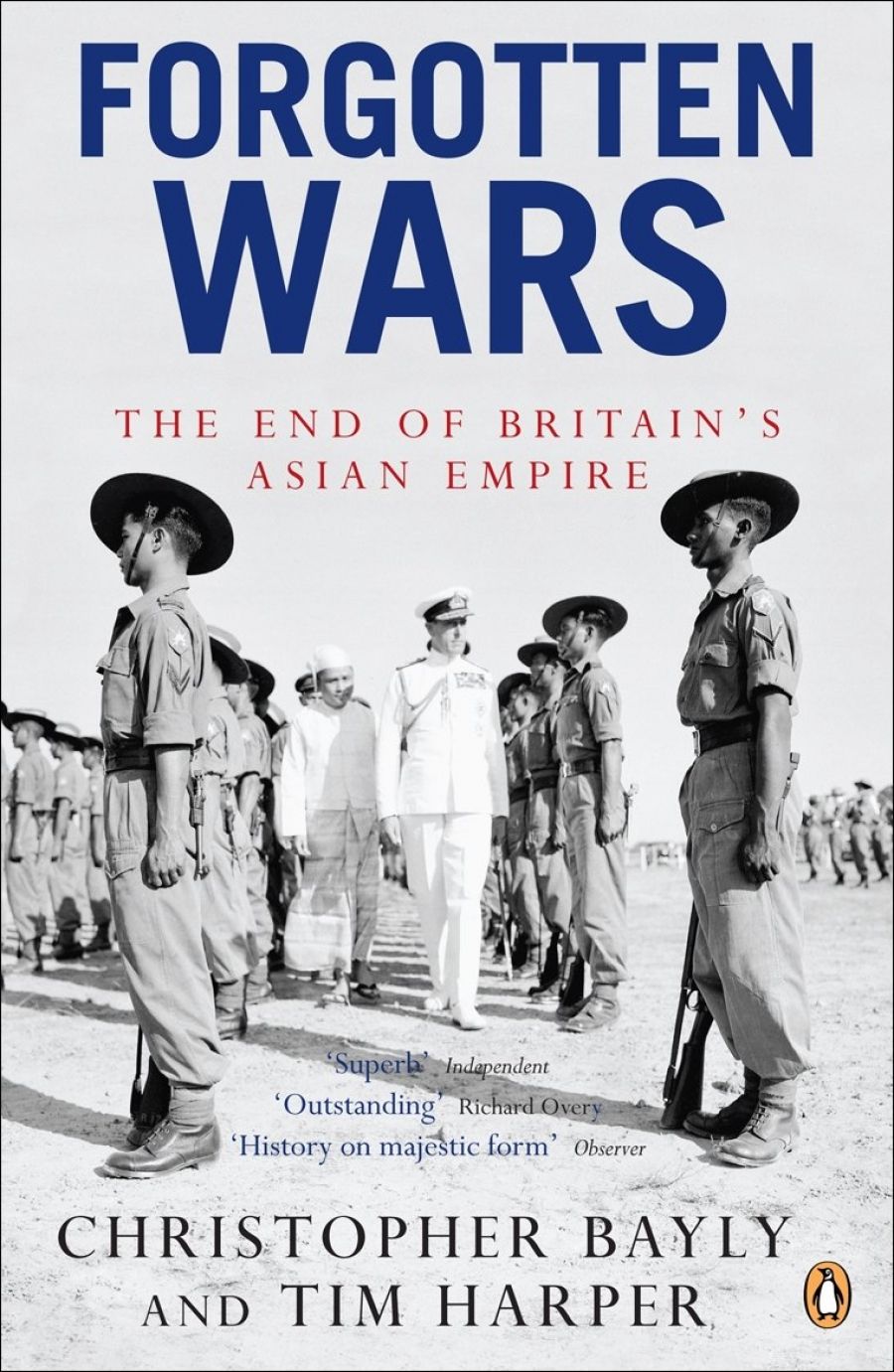

Notwithstanding the old adage, you can tell a certain amount about a book by its cover, especially if it has two covers, each displaying a different subtitle. The British edition of Forgotten Wars, on sale in Australian bookshops, has the subtitle ‘The End of Britain’s Asian Empire’. The cover photograph shows Lord Louis Mountbatten, in spotless white naval uniform, inspecting a guard of honour of Burmese soldiers in 1948. The soldiers appear smart and loyal, while the Burmese civilian accompanying Mountbatten is deferential. The American edition of the book, published under the Belknap Press imprint of Harvard University Press, has the less precise but more evocative subtitle ‘Freedom and Revolution in Southeast Asia’, and a cover with a blurred photograph of a truckload of Asians celebrating ‘Independence Day’. The caption identifies neither the country nor the date, but a likely candidate would be India in 1947.

- Book 1 Title: Forgotten Wars

- Book 1 Subtitle: The end of Britain's Asian emprie

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, $59.95 hb, 704 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://booktopia.kh4ffx.net/gb76Ng

These are, in fact, two sides of the same coin. Forgotten Wars is about Britain’s attempts, from 1945 to 1949, either to re-establish its empire in South and South-East Asia or to withdraw in as graceful a manner as possible. And it is also about the numerous military conflicts and political struggles created by a miscellany of anti-colonial movements – some communist and some non-communist, some nationalist and some separatist, some emphasising and others transcending ethnic and religious divisions – all pressing their claims in a post-imperial world.

The area covered is neither all of the British Empire in Asia, as implied by one subtitle, nor just South-East Asia, as stated in the other. It is the crescent – a word much favoured by the authors – ‘from Bengal, through Burma, the southern borderlands of Thailand, down the Malay Peninsula to Singapore island’. The authors see this crescent as ‘the apex of a wider strategic arc that encompassed Suez and Cape Town in the west and Sydney and Auckland to the south’. There are brief references to the British role in both Indonesia and Vietnam in the months immediately after Japan’s surrender, but these are only subordinate topics.

Australian readers may find particular interest in the brief reference to the role of the Australian communist leader Lawrence Sharkey in the outbreak of the Malayan insurgency in 1948. At the time, it was widely alleged that, passing through Singapore on his way home from an international communist conference in Calcutta, Sharkey brought Moscow’s instructions to the Malayan communists to take up arms. Christopher Bayly and Tim Harper take the word of the Malayan communist leader Chin Peng, in My Side of History (2004), that Sharkey’s advice had been tactical rather than strategic. Australian communists, he told his Malayan counterparts, ruthlessly ‘get rid of’ strike-breakers. He apparently bragged that ‘scabs’ were thrown down mineshafts or otherwise terminated. It was probably braggadocio, but it may have had a greater effect in Malaya than it ever did in Australia.

Mountbatten is central to much of the story – or to the many intertwining stories. The supreme commander of the wartime South East Asia Command (SEAC) who became the first viceroy of independent India, he personified late British liberal imperialism. Some Americans, displaying their Rooseveltian antipathy toward European colonialism, referred sarcastically to SEAC as attempting to ‘Save England’s Asian Colonies’. Other wits contended that it stood for ‘Supreme Example of Allied Confusion’. As this book shows, both interpretations were appropriate for the postwar years.

At the time, and in the subsequent decades, many British policy makers and commentators liked to think that this period was, on the whole, a story of orderly decolonisation, pulling down the flag while ensuring as far as possible that the right sort of chaps were left in charge, while threats from communists and other scoundrels were defeated. Others, at the time and since, have contended that the real story was of Britain’s clumsy, contradictory and sometimes cruel reactions to a confusing melange of rebellions, which forced the exhausted great power largely to withdraw from a part of its empire that was far from home, and far from the preoccupations of western Europe in the opening years of the Cold War. Britain, by this account, was lucky to emerge from the maelstrom of the late 1940s with any credibility, prestige or economic interest intact.

The co-authors of Forgotten Wars are both based at Cambridge University, where Bayly holds the post of Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History. Despite the echoes of ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ in that title, the authors do not indulge in any retrospective flagwaving. There is much more here about confusion, contradiction and incomprehension than about smooth and orderly decolonisation. The considerable detail is linked by a strong narrative thrust, but without an overarching analytical theme. In a sense, however, the theme is that there is no theme – no central and obvious structure to the confusing events of the time. With hindsight, it is easy to see this period as the turbulent transition from the end of a world war to the beginning of the Cold War, but that was far from obvious at the time. Japan’s surrender had lifted the lid on a huge number of competing aspirations and ambitions, some of which would prove ephemeral while others were of enduring importance. Here lie the seeds of much that characterises modern-day India, Bangladesh, Burma, Malaysia and Singapore, but one can feel some sympathy for those at the time who found it hard to sort the substantial from the shallow.

The book’s title owes much to the fact that it is a sequel to the authors’ Forgotten Armies: Britain’s Asian Empire and the War with Japan (2004). That title was well chosen: Britain’s war against Japan has often been neglected in accounts of World War II. It is less clear that the post-1945 conflicts and rebellions deserve the adjective ‘forgotten’. Much has already been written on these conflicts, as the bibliography to this book attests. (The title of this book is also likely to annoy some veterans of the Korean War, who have sought exclusive claim to the title of ‘the forgotten war’.)

What is really innovative about this account is the way in which the authors have put together events across the arc of instability from Delhi to Singapore. Most previous histories have dealt with just one country. Where they have had a wider scope, especially those written after the end of the Vietnam War, it has often been to compare the origins, conduct and outcomes of the Malayan Emergency and the Vietnam War. Many historians in the 1980s and 1990s (including this reviewer) tended to write about South-East Asia in the 1940s and 1950s as ‘the path to Vietnam’. The focus on the British territories in South and South-East Asia, with only passing reference to Vietnam and Indonesia, gives a genuinely fresh context to conflicts that have seldom been linked so imaginatively.

Reference to Vietnam also points to an implicit, or understated, theme. As noted, this is not a flattering account of British policy and its implementation. The authors recall, for example, that the British Military Administration (BMA) in Malaya in 1945 soon became known as the Black Market Administration. The implication is that Britons should be cautious about boasting about their supposed success, by comparison with their transatlantic friend and ally, in governance and counter-insurgency in distant lands. That is probably why the book spends several pages discussing the Batang Kali incident in December 1948, early in the Malayan Emergency. In this incident, still hotly debated after nearly sixty years, a unit of the Scots Guards allegedly massacred twenty-four innocent rubber-tappers. The implication made by a prominent Labour parliamentarian in 1968 was that Britons should be cautious about condemning My Lai and comparable incidents in the American war in Vietnam. Biblical injunctions about casting the first stone come to mind.

Today, as the authors note in the epilogue, the Malayan Emergency is once again receiving attention as the Americans and their allies attempt to retrieve their positions in Iraq and Afghanistan. One possible reading of this book is that Britons (and their allies) should not be too self-righteous about Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo. Supposedly forgotten wars can have their forgotten atrocities, as serious as those recently or currently making headlines in the world’s media.

Comments powered by CComment