- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Reading Tom Keneally is always a delight. As a novelist, he has done much for Australian literature, but his non-fiction is more personable, the product of a sparkling intelligence and keen sense of humour. He is a man with eclectic interests, deeply engaged with the world: both its wonders and its tragedies. One could hardly imagine a less withdrawn artist.

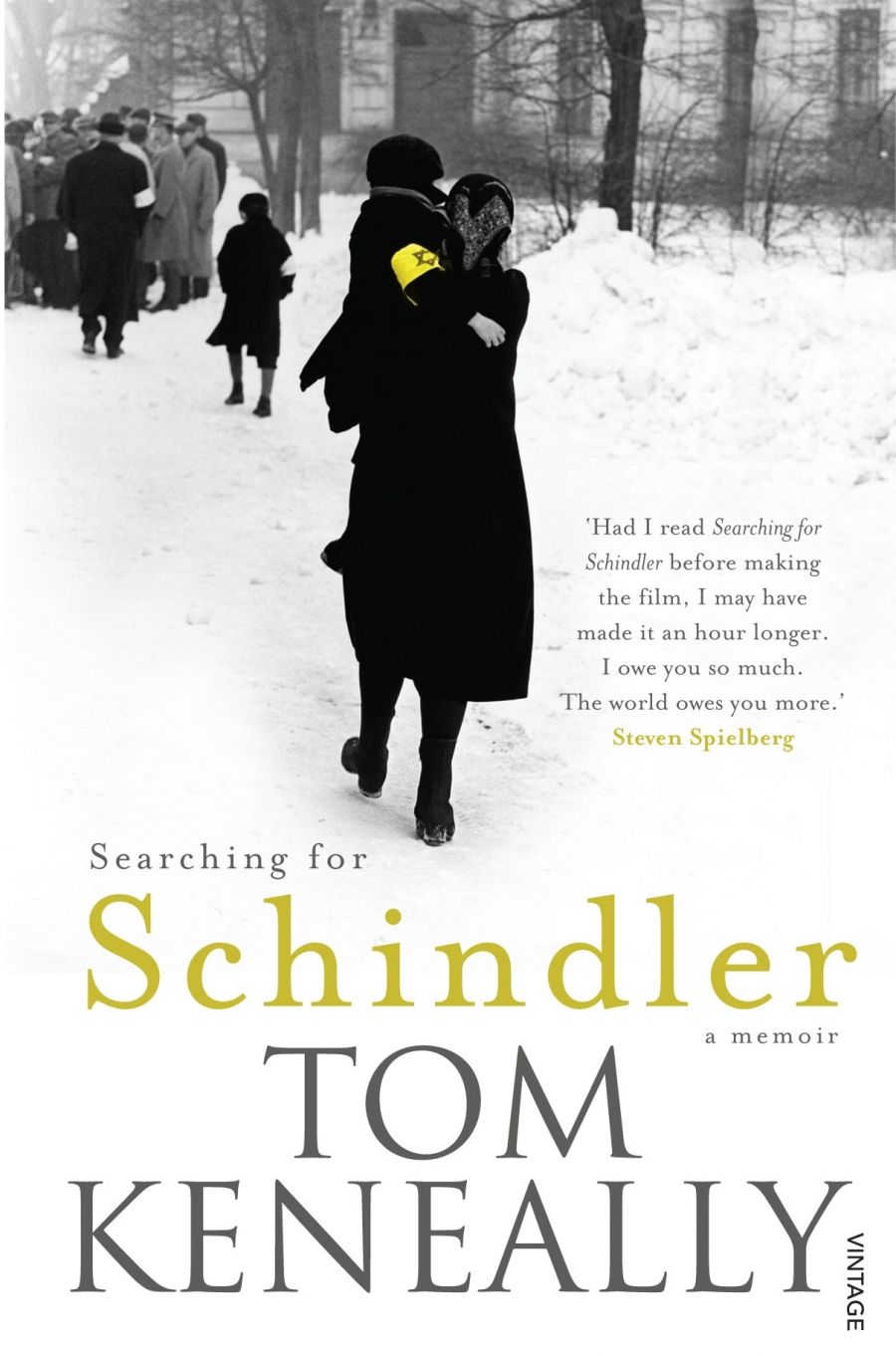

- Book 1 Title: Searching for Schindler

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Knopf, $45 hb, 400 pp

Searching for Schindler is the story behind his most celebrated work, Schindler’s Ark (1982), known as Schindler’s List in the United States. Because this novel won the Booker Prize, attracted significant controversy along the way and was made into an Oscar-winning film by Steven Spielberg (1993), Searching for Schindler should have no difficulty attracting readers, who will enjoy meeting the man behind the novel.

This book is a memory-work in the truest sense: it charts the author’s life briefly, from his childhood to the seminary and beyond, and tells of his early career as a writer. It is mostly concerned with the research, writing and aftermath of Schindler’s Ark, which serves as a rite of passage: this novel made Keneally famous around the world. It is also, partly, a coming-of-age narrative for Australia and Australian writing, as they assumed more prominence on the world stage (particularly in the United States) during the 1980s.

Searching for Schindler is not, however, the work of an introvert: its true subject is the memory of Oskar Schindler, as held by the many people whose lives he saved during the Holocaust. Through his interviews with Holocaust survivors, Keneally is forced to come to terms, painfully, with that most brutal chapter in history. As with any cultural memory, it is not static or unified: the memories of Schindler are as ambiguous and contradictory as the man himself was. Some revere him as a saviour; some resent him for the profit he made out of their lives; some seek to distil his essence of altruism in order to inoculate humanity; and some (his abandoned wife, at least) despise him.

Despite this melange of memories, one stands in the forefront: that of Leopold Pfefferberg Page, or ‘Poldek’, as he is affectionately known. The beginning of the book tells how Keneally, finding himself in Beverly Hills in 1980, in need of a new suitcase, met an idiosyncratic Polish man who, once he heard Keneally was a novelist, convinced him that he had a story for him. Poldek was determined: he wanted to see Schindler’s story recorded for posterity. For Keneally, the lure of a great story was too strong.

Poldek’s memory of Schindler is unambiguous: despite his faults he is a saviour, and his Schindlerjuden owe him a debt. Despite Poldek’s clear opinions, the ownership of the Schindler story does come into question, with associated legal ramifications. Poldek becomes Keneally’s guide and companion in his travels through the United States, Poland and Israel. Through force of personality, Poldek gains access to closed doors and closed minds. In many ways, the book is a memoir of Poldek himself: Keneally applies his novelistic talents to the characterisation, and Poldek is depicted with warmth and affection. He died in 2001, soon after Keneally’s own personal difficulties.

Searching for Schindler will appeal to aspiring writers, not just aficionados, for it tells of the literary process itself. As a full-time Australian novelist, Keneally was a pioneer. His research process involves sifting through a mass of documents on the pool table in his office. At the same time, he portrays the anguish and uncertainty he felt during the writing of Schindler’s Ark. With characteristic cheekiness, he refers to his literary prowess as almost a curse, something like hepatitis.

It is hardly possible to neglect Spielberg’s celebrated film. Keneally is open about his bias towards the novel, and regards cinema as an inferior art form. Nonetheless, he becomes engaged in the process, writes a screenplay (which is eventually rejected), visits the sets and meets all the film people, and eventually loves Spielberg’s rendition of his novel. He clearly feels that the film has done the novel and its characters justice. Although he does relate stories of meeting Spielberg, Bill Clinton, Liam Neeson, Ralph Fiennes and others, it could not be further from namedropping, as his humble attitude makes clear. In any case, much more space is devoted to the Holocaust survivors whom he interviews.

If Searching for Schindler has a weakness, it is that during the long period between the novel and the eventual making of the film, Keneally engages in a fairly long diversion. He discusses his teaching, his current projects and talks, at some length, about his time in Eritrea conducting research for Towards Asmara (1989). The ungenerous reader may see this as irrelevant to the story of Schindler, and may have difficulty connecting it to the memoir proper. However, it is all part of the tapestry of Keneally’s life during the period, and it adds a contemporary relevance to his depiction of a totalitarian environment and the experience of living under an ‘inscrutable régime’. It also attests to Keneally’s strong sense of social justice.

In the end, Searching for Schindler is an engaging and moving account of history, memory, writing and filmmaking, at a time when an author and a nation were still finding their feet. It is testament to the lively nature of a committed humanist.

Comments powered by CComment