- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Science and Technology

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is a timely book. Alan Parkinson argues that the Howard government, which is on the verge of committing Australia to a future in which nuclear power will play a major role, cannot be trusted with the implementation of such an undertaking. A key part of a nuclear programme will be the disposal of nuclear waste, including high-level toxic wastes which will have to be encased in safe storage for thousands of years. Yet the government, which advocates this future, has proved to be singularly unsuccessful in cleaning up the more modest problems from the past – the ongoing saga of the clean-up of the Maralinga test site.

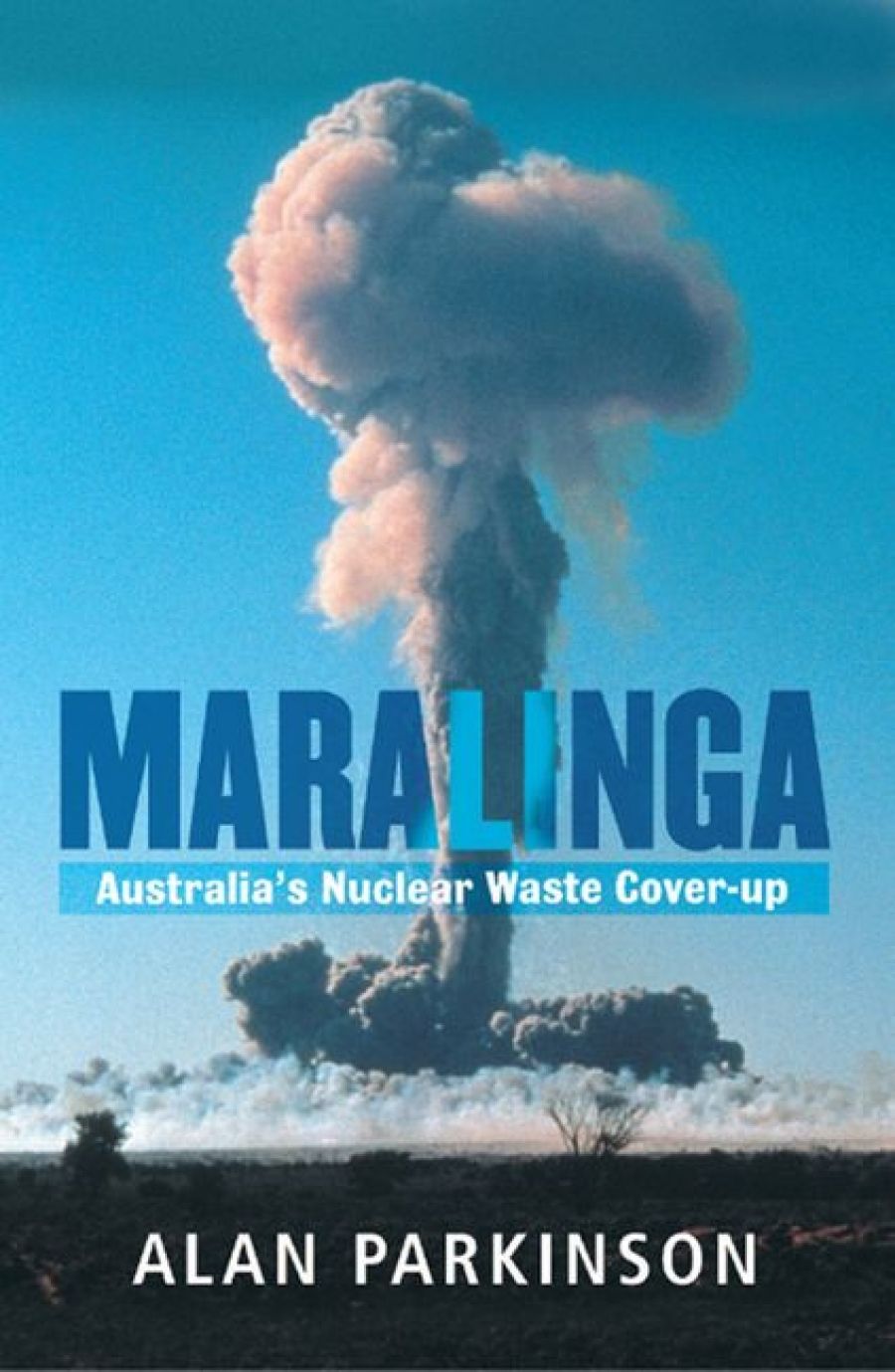

- Book 1 Title: Maralinga

- Book 1 Subtitle: Australia’s nuclear waste cover-up

- Book 1 Biblio: ABC Books, $32.95 pb, 231 pp, 9780733321085

Maralinga was the location of seven nuclear tests conducted between September 1956 and October 1957. This was followed by a series of trials using plutonium between 1959 and 1963. The British progressively ran down the use of the site until 1967 and, after a rushed and botched clean-up, left for good. When they departed, they took 900 grams of the deadly plutonium, but 24,000 grams had been used in the Maralinga trials. Despite this, the Australian representative to oversee safety on the atomic project at the time, the nuclear physicist Ernest Titterton, declared that he was ‘extremely satisfied’ with the treatment of the site. Others were not so sure, resulting in the Royal Commission conducted by Jim McClelland in 1984, which started a major investigation into the mess.

This is where the author came in. Alan Parkinson, a mechanical and nuclear engineer, has more than forty years’ experience in the nuclear business. Parkinson advised on a range of options to clean the site. He was particularly impressed by the American scheme, which had been used on less toxic sites than Maralinga, and which reduced nuclear waste using in situ vitrification (ISV). Essentially, the most toxic wastes were melted on site and formed into a rock-like mass that would neutralise the plutonium for thousands of years. The focus of Parkinson’s work was the Taranaki site near Maralinga, where the most toxic wastes were buried in a number of shallow earth pits.

Parkinson was no greenie: he thought that the ISV process was exciting and he looked forward to working on it. He does not say so, but in the event that it proved to be successful and Australia were to host an international nuclear waste dump of the type floated by the Pangea consortium in the late 1990s, then this technology might have been appropriate. In any event, Parkinson obviously impressed those charged with the clean-up. He was appointed to the Maralinga Rehabilitation Technical Advisory Committee (MARTAC) in late 1993, and in April 1994 was appointed by the government to help oversee the clean-up of the contaminated top soil. In November 1996 his role was extended to help oversee the ISV process.

Then things started to go wrong. In August 1997 a company called GHD arrived on the scene and was given responsibility for the management of the ISV work. This astounded Parkinson. The company did not have the reputation for the nuclear clean-up business and was not even short-listed in the tenders for the job originally. It then decided to limit the number of pits for ISV treatment, adopting a so-called ‘hybrid solution’. Some pits were to be treated and others merely covered in shallow earth, without a satisfactory inventory of their contents. It was at this juncture that Parkinson found himself seriously at odds with the new management. To him it was about quality control and professional standards; to the company it was about working with management. Inevitably, Parkinson found himself isolated from decision making, and it was not long before he was dismissed from the project and from MARTAC. GHD then stopped work on ISV in June 1999, and the remaining pits were covered. Just over a year later, Senator Nick Minchin declared Maralinga safe.

This might have been the end of the story. But Parkinson did not leave it at that. It gradually dawned on him that GHD had been brought in to save money – the ISV process was too expensive. Like so many government projects in the early Howard years, the need for economy and the attendant move to outsource work, torpedoed the Maralinga clean-up. Parkinson took the story to the media and into federal politics. Progressively, he found allies in the Democrat Lyn Allison and Labor’s Kim Carr. He also found an attentive audience in the ABC – starting with an interview with Background Briefing, in April 2000 – which ultimately led to the publication of this book.

The book is something of a hybrid. Parkinson devotes a lot of space to describing his own experiences at Maralinga: his love of the land; his work on a range of things quite unrelated to the thesis of the book; the early details of the clean-up. It reads initially like an official history, with much narrative detail, leaving the reader to wonder where it all leads. What is the great cover-up? There is also much about Parkinson’s reputation as a dedicated and conscientious scientist – which is understandable, given his treatment. He does not, however, have to dwell on this, as the second half of the book amply demonstrates. When he draws together the details of the cover-up – the saving of money, the compromises in public administration, the political misrepresentation by the Howard government – he provides a most compelling critique. It is also clear that his public campaign has contributed to a three-year delay from Senator Minchin’s declaration that Maralinga was safe to the release of the flawed MARTAC final report. In the coming nuclear debate, Alan Parkinson will be an interesting figure to watch.

Comments powered by CComment