- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Graham Swift’s fine novel Last Orders (1996) is propelled by the motif of a group of middle-aged men, with a shared past, brought together again by a single goal. In their case, it is the matter of casting the ashes of a dead friend into the sea. The narrative dips into the characters’ past to acquaint us with the nature of the ties that bind – have bound – them to each other and to the dead man.

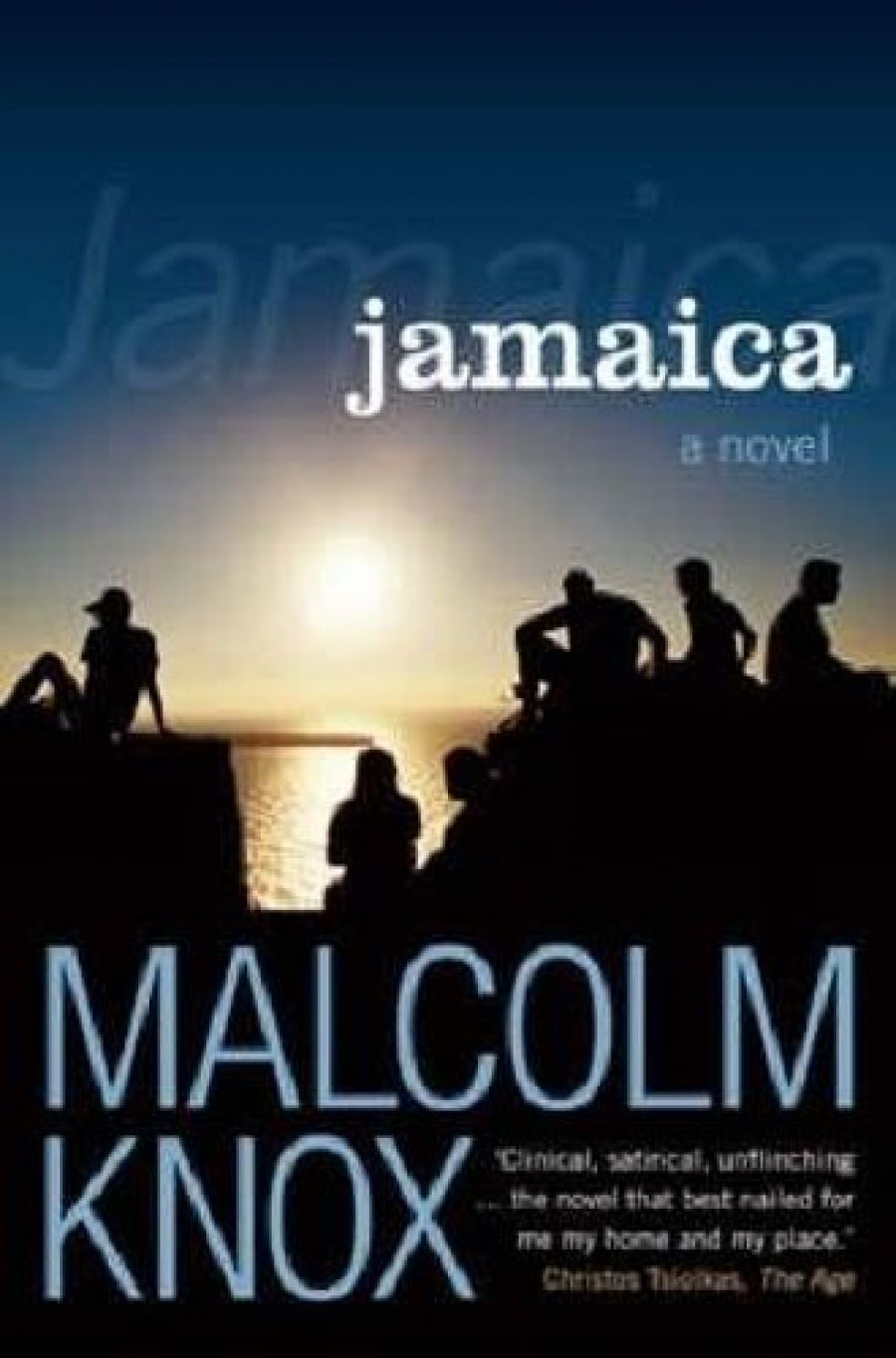

- Book 1 Title: Jamaica

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.95 pb, 388 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/x9k66A

Malcolm Knox’s Jamaica offers a rough parallel, a variant on this potentially rewarding paradigm. Five men – forty-somethings who have known each other at least since university days, in a couple of cases much longer – and one woman are headed for the eponymous tropical paradise (not). They are booked to do a perilous marathon relay swim, in which sharks are the least of their problems. The most may well be that, as the pilot of the boat accompanying them makes clear, if they swim away from him they can keep going until they reach Venezuela, because he is not going after them. This race is the purpose of their five days in Jamaica. As in Swift’s tale, Knox keeps back-flashing to fill in the nature of their connectedness and how their Australian lives have been shaped by parental and other aspirations.

The big swim (one thinks, not altogether irrelevantly, of the film The Big Chill [1983], which involves similar reappraisals of old associations) is meant to be an occasion for bonding, confirming one’s suspicion that bonding occasions are to be avoided at all costs. Old amities are unravelled and latent hostilities break through to the surface. A sense of ‘division’ is proleptically signified in the way that three of the team sit huddled in Economy Class, while the other three luxuriate in First, with Jeremy Hutchinson (‘Hut’) leaving the latter momentarily to be nice to the three below; his will hereafter be an intermediary’s role.

Of the six, Pongo (Justin Pongrass) and Abo (Andrew Blackburn), in First, come from the poshest schools and oldest money, and have acquired the vilest responses to everything. Pongo’s conversation is mainly about the ‘firsts’ that have coloured his sex life. In Economy are decent John Bookalil, ‘who had lived in the same suburb his whole life’; Janey Quested, who once ‘dat[ed] a university medallist in drinking’; and, most enigmatic of the sestet, David Nayce, son of the manse and Hut’s friend, to use the term equivocally, for thirty-five years. Hut is the son of a cockney entrepreneur who has acquired money and a statuesque German wife, but the shaky background he has provided for Hut means that the latter is always trying too hard to please everyone, specially the obnoxious Pongo and Abo, and his wife, who refers to him, more or less affectionately, as a ‘fucking arsehole’.

The race is at once the climax and of no real account. There are more interesting things going on than this. For instance, there is an appalled fascination with the way the Westerners react to the Jamaicans, whose names they can’t be bothered remembering and one of whom exacts a grimly comic revenge. In a late-night escapade, Hut, desperately sucking up to Pongo and Abo, goes in search of ‘It’ (cocaine) and finds himself utterly disorientated in a crowded market, unable to find his way out and finally laid low by a bruising encounter with a passing car. On another night, Pongo scores a sexual hit in a banquette at the Palais Royale with a black lady who in turn reprimands him for blasphemy.

Hut comically interrupts this latter episode with a request for professional legal help, and reinforces our sense of his ineptitude and his outsider status among those he inanely wants to impress. Hovering over the book’s concern with the connections among The Fast Set, as they designate themselves, is the growing certainty that something has gone very wrong for the well-meaning Hut. He is in serious, possibly criminal, trouble; his old friend Nayce lets the bitterness and mean triumphs of years past spill out as they sit by the edge of a volcano; and Hut’s exasperated wife is on her way to the island for a confrontation.

Knox exercises firm control over the sprawl of years and the convolutions of friendship and idiot competitiveness that the six have so carelessly maintained and indulged. He distinguishes subtly enough among the degrees of folly and self-absorption these largely unattractive characters exhibit, and does so with flashes of wit that especially savage Pongo, who ‘didn’t go in for racism. Racism was a lower-middle-class kind of thing, like state politics and pop culture.’ And the beach house that Hut’s family regularly rents is architecturally a case of ‘Michelangelo meets Godspell’. The wit and satirical accuracies are the book’s trumps; and there is verbal playfulness in the unexpectedness of ‘he wheeled and dealt’ or ‘a white-sandshod foot’, but let Knox near a sunset or dawn and the style founders drunkenly. ‘In a slotting of light caused by a shelf of cloud above the horizon, the sun’s reddening glow fattened, a vast slash of blood between the greys of sky and sea …’; elsewhere, ‘The rising sun laid out a pink blanket for the setting moon.’ When it leaves the natural world alone, Jamaica is good, nasty fun; just the thing for a long flight, in either Economy or First.

Comments powered by CComment