- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If the central, not-made-much-of miracle in Craig Sherborne’s remarkable memoir Hoi Polloi (2005) is the disappearance of the narrator’s childhood stutter after a blow to the head, then the equivalent motif in Muck, Hoi Polloi’s equally fine sequel, is his voice.

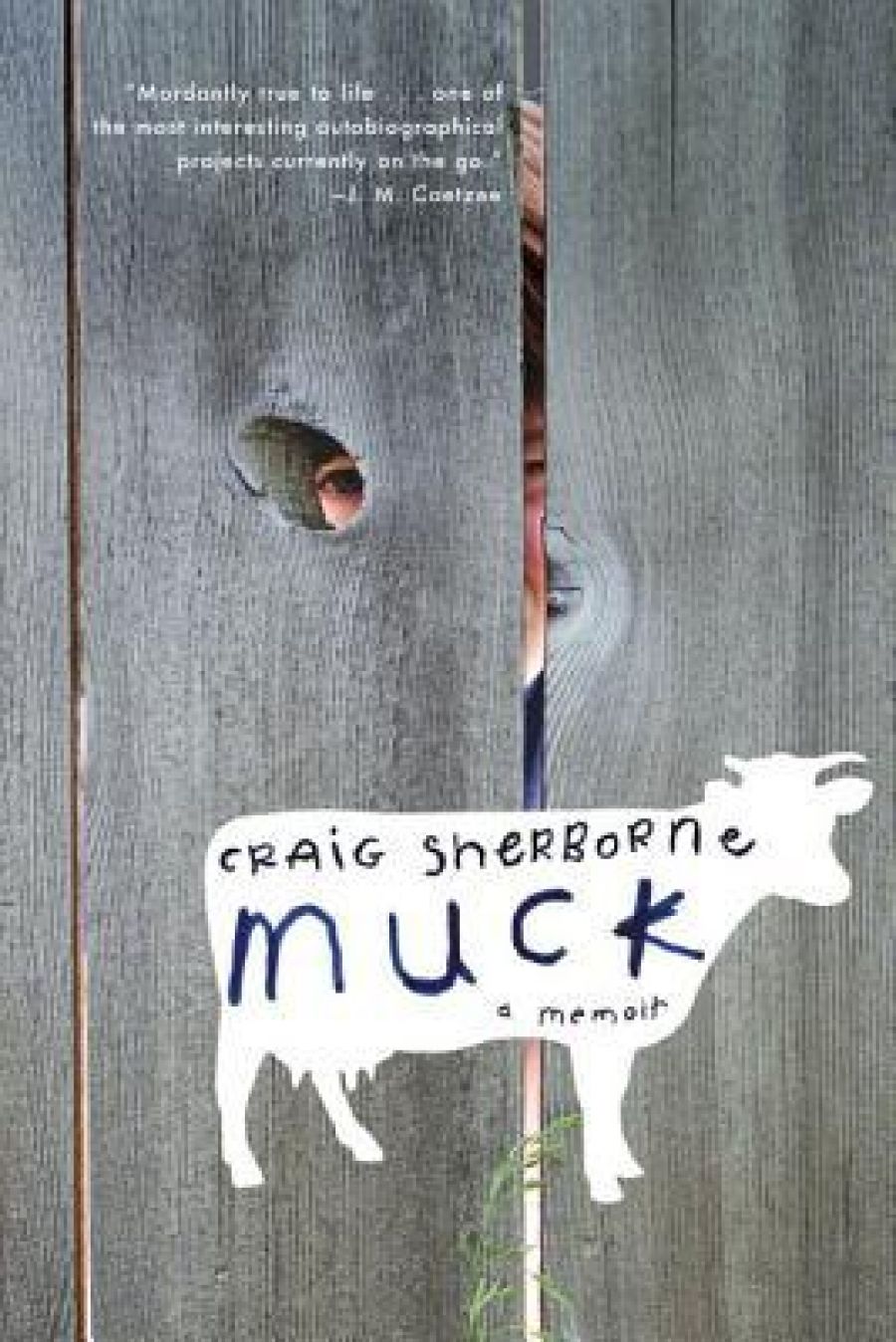

- Book 1 Title: Muck

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $27.95 pb, 195 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/0kbRL

Things are looking up. The Duke’s wife, always Heels to her son in Hoi Polloi (heels ‘like a cocktail glass for her feet’), mock-complains about country life but is secretly thrilled to be gentry and pushing towards posh. She names the place Tudor Park. Milady she may be, but she still gets down on her knees and scrubs the doorstep in order to keep the cow muck out of the house. She is fifty-three; ‘her heels are bare and cracked now, chalky around the splits’. Heels turns into Feet.

Only rarely is Feet referred to as a mother. Much of Muck is chilling, and the deliberately merciless, apparently unforgiving portrait of Feet is its chilling core. Throughout Hoi Polloi, Heels, a bundle of airs and prejudice, strut and flutter, lipstick and hairspray, Anglo-Saxon attitudes and aspirations, is amused, exasperated and appalled. In Muck, she is strident, tragic, out of control, beyond redemption, almost beyond black comedy. The narrator, a young man of sixteen manipulated by the mature literary stylist he has become, aligns himself with The Duke, but the latter is in two minds about education and the boy has an ear for poetry. He is also susceptible to a particular cow.

The whole damn family, including its sole heir, is forever climbing and having to settle on a broken rung somewhere ten and a half steps from the top, bruised by the fall. The only child is a festering contradiction of impulses and embarrassments. But the boy can sing.

I want something new to impress them. They won’t expect Blake’s dark satanic mills, his arrow of desire, in the manner of Dean Martin: I swallow the words into my throat to be trapped there at the back of my tongue for lazy vibrato. A drunk-like slurring and dying fall to the last long word of the first verse.

The narrator is at his school in Sydney, the school he shares with The Citys and The Scrubbers. It is morning chapel and he is flaunting his ‘vocal jewellery’. He shifts to Tom Jones for the second verse, shifts again, this time to Engelbert Humperdinck’s nasal drawl, and finishes with an inspired flourish, his Louis Armstrong voice. He considers confessing. ‘Call me up to the front and punish me, Reverend. Make me the famous among my not-friends.’

Feet reckons that he has inherited her musical gifts, which are nil. She’s in an orange housecoat, rucked up, smoking a cigarette, and there’s another glass of wine: ‘Sing into my eyes. Kneel down. Sing it like you mean it from your heart.’ He’s Jim Reeves, he’s Nat King Cole, he’s sixteen and they’re the wrong songs for someone this age. Later, at the races, he’s swaggering, acting again, faking sophistication, and he makes a total fool of himself. He becomes a drunken embarrassment to The Duke, who had embarrassed him with introductions to the high and mighty The Duke doesn’t really know. All the world is a terrible, vulnerable con. When the poignantly combative narrator is chosen to sing the lead in the school’s musical adaptation of The Catcher in the Rye (which, of course, he has read and admired, even though he makes little of his reading in the memoir), he sings, ‘Elvis Presley-perfect’, a scale for the music teacher whose response is, ‘This is a school play in Bellevue Hill, not the Mississippi ... To be an imitator is all very well but I want the original you. Do you have a you?’

It is the increasingly grotesque Feet who wants him Elvis Presley-perfect, and the missing you is hauled back to Taonga and the newly built Tudor Park mansion before finding himself. Feet has committed monstrous mother-crimes, and become more and more pathetic. Will he sing for her? He will not.

Let her swoon all she likes at the thought of a serenading. Sung to sleep as if drugged by me, a snake charmer for humans. I will not sing to her.

I sing Love Me Tender.

I sing Embraceable You.

Of one thing I am certain: Muck is indivisible from Hoi Polloi. If Muck beckons, you should read Hoi Polloi first. Muck is borderline self-contained, filling you in, for instance, on the gloriously abject shift that turns Heels to Feet and Winks to The Duke, but the reader who hasn’t meet Heels’s younger self will miss the full power and smack of the prose, in particular the terrible fall from teetering grace that Heels propels herself towards. The full melt of tenderness which is the narrator’s almost-secret won’t wash over you either, and the full impact of the central theme of the memoir, the unavoidable family connection, the burdens of the only child, both physical and emotional, will be lessened. In his poem, ‘Ash Saturday’ (ABR, October 2005), Sherborne wrote about his father’s death, about tipping the ashes into the sea. The first line reads, ‘There is no God, I was made in this man’s image’; and the last, ‘But death’s no mystery, not to me, not now. / I am its DNA.’ In between the first and last lines, there is a muted return to the mockery, the tender cruelty of the memoirs, but this pose, this partaffectation, has always been, I suspect, a shadow-boxing game in the adolescent narrator’s head, a ruse for the survival of a poet.

In his review of Hoi Polloi (ABR, September 2005), David McCooey pointed out that the narrator is ‘far from innocent when it comes to his own emotional hypocrisy’. This lack of innocence, which continues into Muck, is a compound issue – the author as narrator – and is central to the brilliance of the telling. Sherborne has created a narrator who is victim, supplicant, acolyte, a poignantly defiant rodomontade with a fiercely tender core, and it is a powerful, contradictory mix. Muck – pitch-perfect – bowls you over, as if it is a form of rhetoric, which Socrates, in his wisdom, defined as a kind of flattery.

Comments powered by CComment