- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Cracks still show

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

and from every dead child a rifle with eyes,

and from every crime bullets are born

which will one day find

the bull’s eye of your hearts.

And you’ll ask: why doesn’t his poetry

speak of dreams and leaves

and the great volcanoes of his native land?

Come and see the blood in the streets.

Come and see

the blood in the streets.

Come and see the blood

in the streets!

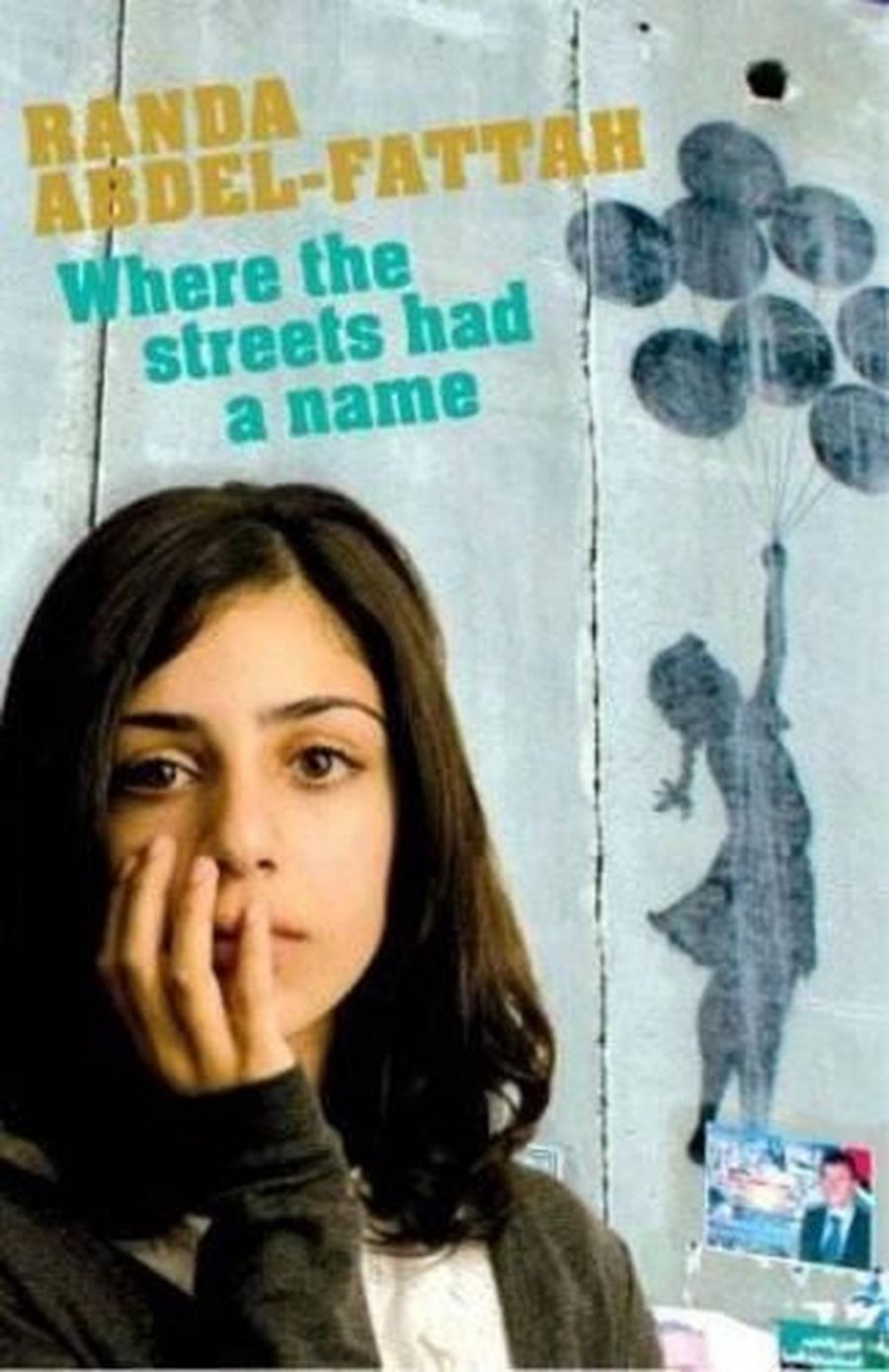

So wrote Pablo Neruda, of the Spanish Civil War (‘I’m Explaining a Few Things’, 1947). These words could apply in any place where children are made to suffer and thus to hate. Randa Abdel-Fattah’s Where the Streets Had a Name is a book whose pages resonate with these themes, unflinchingly; remarkable because hers is a book written for children and about children – those living in the West Bank.

- Book 1 Title: Where The Streets Had A Name

- Book 1 Biblio: Pan Macmillan, $19.99 pb, 287 pp

On one level, Abdel-Fattah’s narrative traces a seemingly simple, fantastically conceived journey by its protagonist and narrator, Hayaat, and her mischievous friend Samy, from the West Bank, from behind Israel’s infamous wall, to Jerusalem’s Old City. In early chapters, the book describes the lives of its characters in wonderful detail: their families, their laughter, life under occupation, endless curfews, fear, loathing, pain, and the drudgery of routines. Yet there is nothing quotidian here. All of it is everyday, but outside most people’s reality.

Just so, the impetus for the book’s central journey stems from the simple imaginings of a thirteen-year-old child, or else the evocation of a child’s eye view of an all too adult world. ‘If I could have one wish, Hayaat, it would be to touch the soil of my home one last time before I die. Land, ya Hayaat. There is nothing so important.’ Hayaat determines that, despite the checkpoints, her lack of permits, and the real dangers lying in her path, she will fetch for her grandmother some soil from that home.

Abdel-Fattah’s style is a beguilingly and deceptively simple one, perfectly suited to her young adult audience. There is a poignancy in the telling of so harrowing a narrative from a child’s perspective; the child’s view, as the prism through which we see the world, is an extraordinarily powerful tool. This is what Harper Lee managed so deftly with To Kill a Mockingbird (1960). The effectiveness of this device, though, rests on the accuracy with which the child’s voice is evoked. Aside from a handful of clumsy instances, Abdel-Fattah accomplishes quite a feat, mixing everyday horrors, hardships and frustrations with an underlying innocence and childlike quality on the part of her characters. Humour is never far beneath the surface, despite the wounds these characters have suffered, both external and internal.

There is, then, the second level of the novel: the inescapable polemic that underscores the narrative. Having written her book for a young adult audience, Abdel-Fattah owes something to the reader by way of a more balanced representation, if only in positing the other view then having it discarded and rejected by the main protagonists.

Save for one throwaway passage, there is no real reference to militants: Hamas, al Fatah, the intifada, suicide bombers. Yet these are a real feature of life in the occupied territories, and they do tell a story and flesh out some of the underpinning tensions, motivations, ideological positions, and rivalries both between Hayaat’s people and the Israelis, as well as amongst warring Palestinians.

For all that, this novel captures the heart and soul of a people trying to make something out of the terrible hardship and burden of their indignities. The confiscation of land, the bulldozing of homes, the impact of a wall, death, loss, poverty, lack of hope and the terrible crush that comes from having to explain these to one’s children, and salve their pain when there is so little left.

What Abdel-Fattah manages best is to evoke a broader sense of her adult characters’ innocence, their child-like qualities, their humour, jokes, anecdotes, and the religiosity and superstitions that they harbour. These are a damaged people, robbed of their hopes, dreams and capacity to grow.

As Hayaat’s father tells her, ‘You’re stronger than I am. Sometimes I feel like I’ve failed you all. I cling to the past when I know it’s dangerous to do so … but if I let go, what else do I have … On my land I was able to give you more, and they took that from me. I wish I had your courage Hayaat.’ Of her scarred face, Hayaat explains, ‘I’m like a shattered glass pane. Even when you put the glass back together, the cracks still show.’ We know she is speaking for a people who cannot see a bright future because they are not allowed to, though they yearn to do so.

The future remains in the hands of the adults of tomorrow. It seems that what Abdel-Fattah longs for most through her characters is a time when poetry will again speak of Neruda’s dreams and leaves.

Comments powered by CComment