- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Being there

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There are traces of a constant, oscillating motion of conscience in Sandy Fitts’s poetry. References to the burden of ‘history’ pit the poems, with ‘history’ standing for everything we need to address in the present, through the power of eloquence, but also in fear that such words are not enough. From the opening, prize-winning poem, ‘Waiting for Goya’, to the closing images of ‘Blue Mop’, the act of poetry emerges and is scrutinised for what it might do in the world:

our figures leaning toward each other

to exchange a few uncertain words

about the mop- utility- aesthetics-

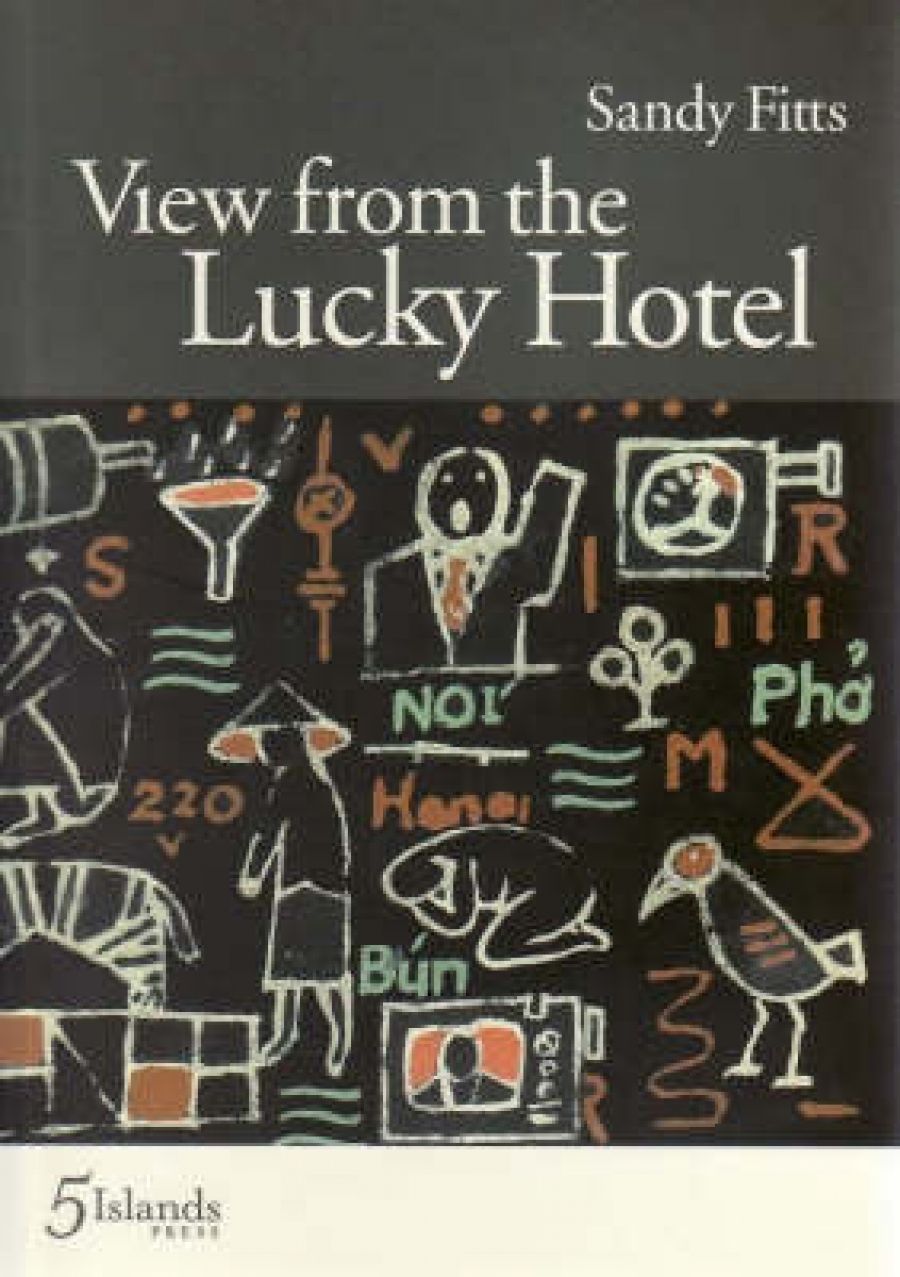

- Book 1 Title: View From The Lucky Hotel

- Book 1 Biblio: Five Islands Press, $19.95 pb, 83 pp

This is, I would venture, unfair to Baudrillard, the speaker confusing the author with the strength of his ideas. But some might agree with the poet. After all, the passage that follows, set in modern-day Vietnam, contrapuntally worries about ‘this old war zone transformed to theme-park’. I am not convinced that being ‘there’ is necessarily superior to writing about ‘there’. The tour of the old Viet Cong war sites in ‘Củ Chi Tunnels’ is narrated as an awkward, embarrassing and even horrifying experience to the group of camera-wielding tourists, so does that add up to ‘being there’? Perhaps it does for a poet who records the tourism and the angst in equal amounts.

In another approach to the question of poetry and its power – or lack of it – ‘On Visiting Hỏa Lò Prison (1896–1996) Museum’ is painfully aware of the poet’s dubious role as ‘Witness or voyeur’:

Staked out now by tourism and history, reality is struggling

in the exchange between their hard currencies. How to stand

on ground soaked with blood, human shouts, and falling?

How indeed. Here the poetry teeters on the brink of complicity. It is not that Fitts’s poetry isn’t highly self-conscious of this paradox. She plays with it over and over in her appropriation of history and theory for her scenario of guilt. The momentary resolution of this poem is the plaintive question: ‘To stay alive, does history need transfusion, vein to vein?’

As a reader of both poetry and theory, I am deeply interested in such questions. But I find the middle-class angst of some of these poems less compelling than the poetic moments which offer a richer, more complex set of possibilities, both for poetry and for ethics. When I am asked, in different ways, in these poems, ‘Who said all aesthetics are forms of ethics?’ I want to cry ‘Not me’, just to be contrary. But that wouldn’t be helpful. I do want to think about the aesthetic and the ethical in relationship, but I think Fitts does this most tellingly when her poetry picks up the question in a more embodied, contextual, poetic way.

This may be yet another version of ‘poetry should show and not tell’, but so be it. For example, in the fine tracing of two women travelling across an Australian desert landscape, ‘Lips are moving words / more slowly, bestowing a vatic formality upon / the commonplace’ (‘Visiting the Centre’). The observer and the land are seen to be in relationship in a subtle, humble way; the speaker, sprinkled in fine dust, bows: ‘Each detail calls out, as though carrying a truth, / while thoughts fall in fragments.’ The poem traces a blessedness here in letting thoughts fall, in desiring first ‘… a brave voice – and strong – / strong enough to celebrate this time, this place, / our tiny moment, blinking like an eye / in the history of everything’.

With an impressive range of poetic forms, View from the Lucky Hotel works through two separate halves. The first half is more loosely structured around lyrical memoir and tribute. The second narrates a journey (or several) to Vietnam, and particularly Ho Chi Minh City. While there are interesting and often humorous observations of this city as it is gradually encroached upon by glossy new hotels and tourism, most memorable are the details of everyday life and relationships: ‘Friday night we roll out the matting to sit around / the aluminium serving tray with its six bowls. / As guest I sit next to your husband Nam / then young An and Giang and the blind aunt who / declares this meal gives strength to friendship / prefacing a stillness – incandescent …’ There is no need to paraphrase the ‘ethics’ of this scene. It hovers, palpable, as the family and guest eat together, carrying ‘… the dripping flavours to our mouths / translucent as meaning complex as pleasure / phở gà fragrant with lime and coriander’. Not poetry as ‘lousy legislation’ – but much better than legislation.

Comments powered by CComment