- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: On the bridge

- Online Only: No

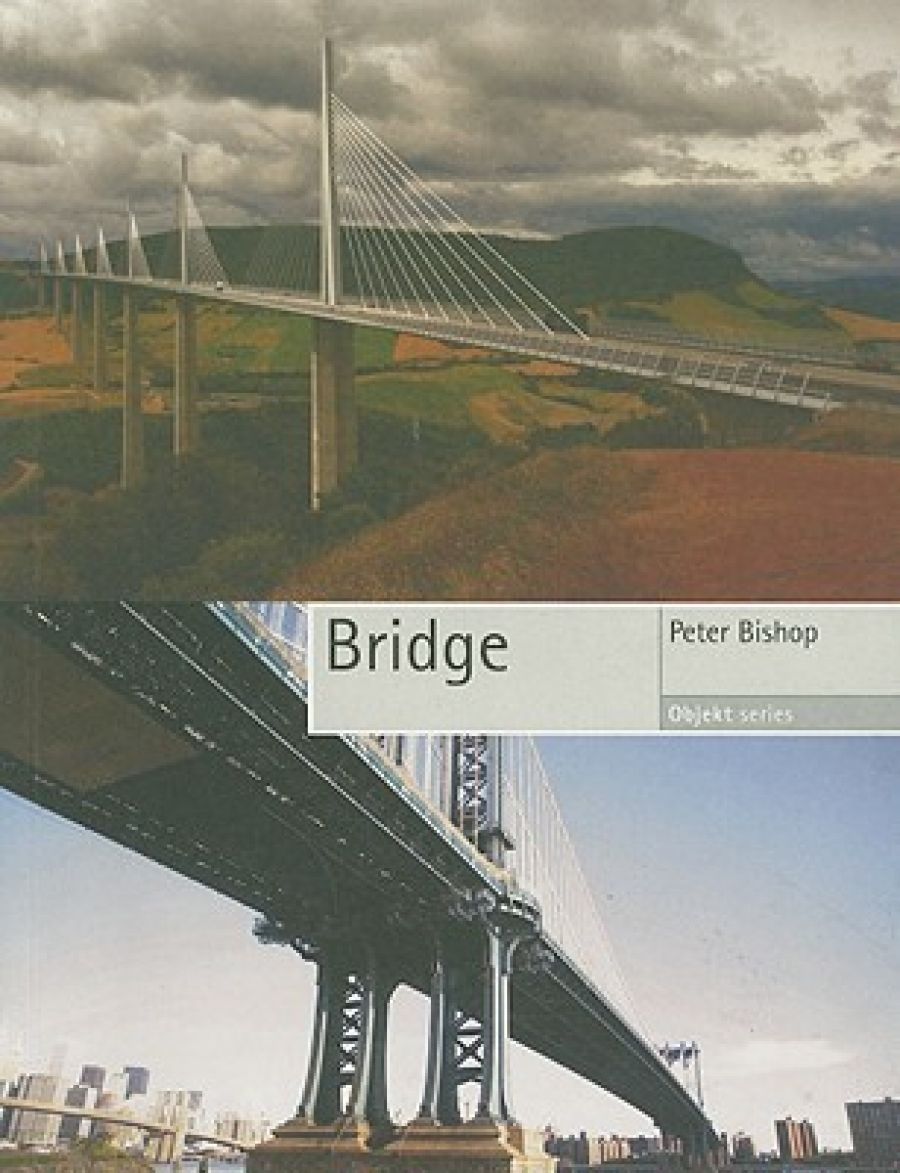

- Custom Highlight Text: Peter Bishop’s book on bridges is the latest in the Objekt series published by Reaktion. It joins other books on the factory, the aircraft, the motorcycle, the dam and the school. The series focuses on the last hundred years, although Bishop traces the story of the bridge back to the early nineteenth century. Bridge is not, however, a straightforward linear history. Instead, it seeks to examine ‘the bridge (bridging and bridge-ness), along with the cultural practices – from the civic to the military, architectural to engineering, artistic, poetic and philosophical – that have circulated through it over the past two hundred years, from the onset of modernity to the dawn of the new millennium’. The result is an interesting and accessible, though necessarily selective, account of bridges and their cultural significance.

- Book 1 Title: Bridge

- Book 1 Biblio: Reaktion Books, $49.95 pb, 240 pp

Along the way he looks at iconic bridges such as the Golden Gate Bridge, the Brooklyn Bridge, the bridges over the Thames in London and, of course, the Sydney Harbour Bridge, as well as less familiar ones. He would appear to be perfectly placed to write a study of this kind, having at one point been involved in bridge design himself (though he never quite states in what capacity).

Bishop is particularly good on the cultural and political consequences of bridge-building. In his account of the bridges (which number over six hundred) of the Qinghai-Tibet railway, for example, he pays equal attention to Chinese boosterism (the railway as an ‘Engineering Miracle’) and to the misgivings of Tibetan activists (the railway as a threat to the survival of Tibetan cultural integrity). He also puts the vast project into a historical context, suggesting that its direct ancestors are the early nineteenth-century British rail and bridge networks. Bishop is undoubtedly right to emphasise the nation and empire-building roles of the bridge in contemporary China as much as in nineteenth-century Britain and its colonies.

Bridges dramatically modify the landscape, as Bishop frequently points out. That landscape, however, is not an exclusively cultural and political one. Reading Bishop’s book, I began to wonder whether the bridge as a type of quintessentially, though not exclusively, modern object, embodies an equally modern attitude towards the natural environment as a terrain to be altered at will that may, in our postmodern (or post-something) present, be outmoded, albeit not in China. It is surely no coincidence, for instance, that the construction and subsequent completion of the Sydney Harbour Bridge was a favourite subject of some of Australia’s earliest modernist painters – Grace Cossington Smith, for example. Yet much of the celebratory discourse around bridges implicitly appropriates that category of aesthetic experience that was, in the eighteenth century, usually reserved for the description of nature or rather the experience of nature – the sublime.

Bridge is lavishly illustrated, though at times the placement of the figures seems rather arbitrary. Image and text do not always seem to relate, and in places it would have been helpful to have had more, or different figures so as to grasp Bishop’s point more easily. That said, this is patently the work of an enthusiast and a worthy contribution to an important new series of books.

Comments powered by CComment