- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Flinty connections

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the introduction to her Virago Book of Fairy Tales (1990), Angela Carter considers the contrary nature of the fairy-tale form. Born of a lively oral tradition, fairy tales are not beholden to veracity, and Carter celebrates the complete lack of desire for verisimilitude in Andersen, Grimm and Perrault: ‘Once upon a time is both utterly precise and absolutely mysterious: there was a time and no time.’ Fairy tales do not beg the reader to suspend their disbelief, they baldly expect us to see the thing for what it is: a tale, a lie. It is all in the telling: which parts of the story the narrator wants to illuminate; which parts she wants to subvert or leave out completely. Carter writes of the modern preoccupation with individualising art, our cultural faith ‘in the work of art as a unique one-off, and the artist as an original’, but fairy tales are not like that. They eschew permanent ownership and the responsibility that implies.

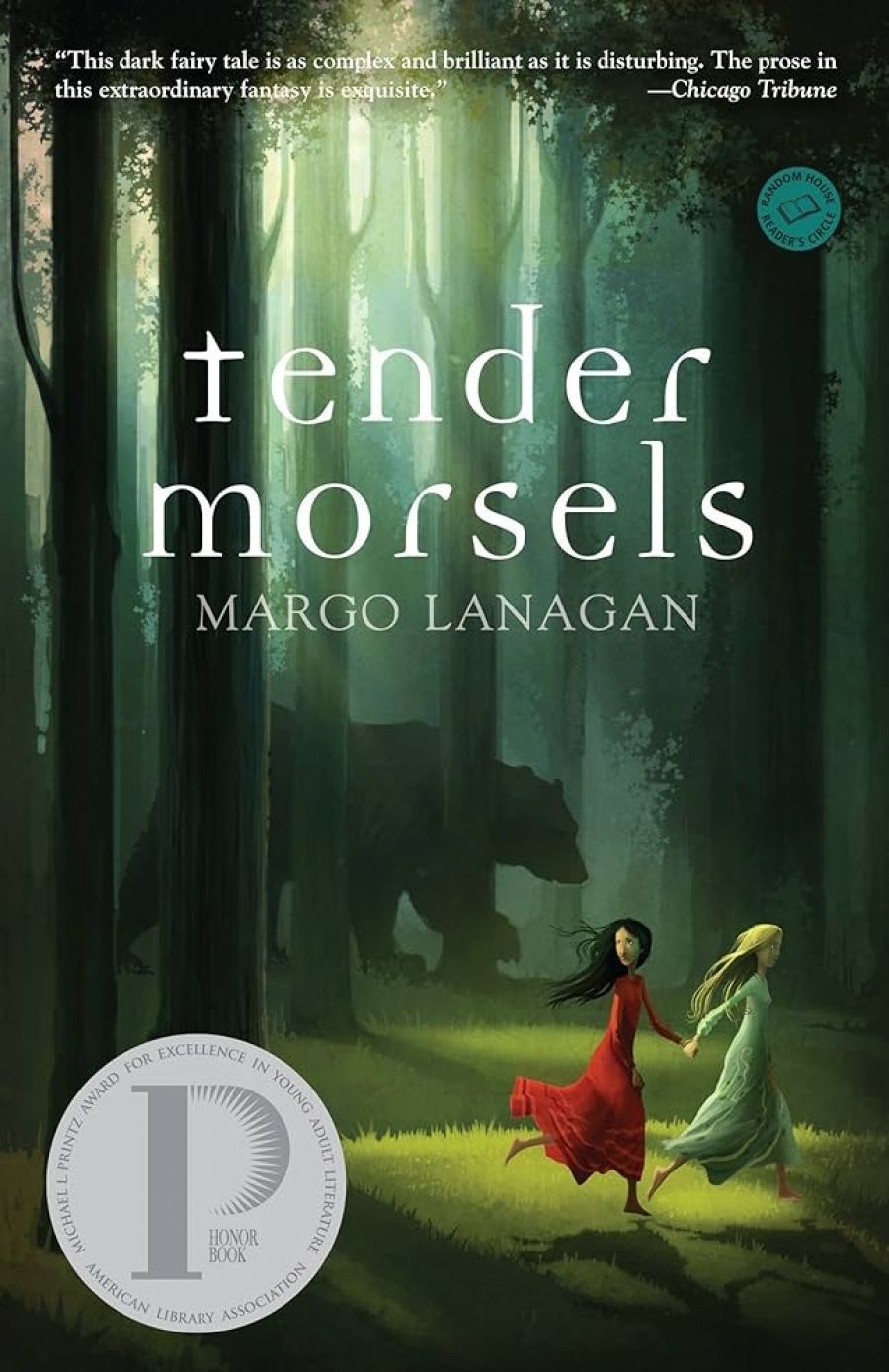

- Book 1 Title: Tender Morsels

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.95 pb, 362 pp

Tender Morsels is Lanagan’s first novel for adults. It is speculative in style, much like her award-winning short story collections, Black Juice (2004) and Red Spikes (2006). It shifts between parallel worlds that are both terrible and familiar. Liga is a young peasant woman who lives in an isolated cottage with her ogre of a father. Her life up to this point has been brutal and, for the most part, empty of love. Afraid and tired of suffering, she stands on the edge of a ravine, intent on suicide. She holds her infant daughter, Branza, in her arms, unaware she is pregnant with her second daughter, Urdda. A mysterious vision convinces her to leave the abyss, return home and plant two magic jewels in her garden. Her world now becomes quiet and tranquil; she is free to raise her daughters without bullying or interference from other people. Liga’s daughters grow up believing this to be the real world, but Liga understands that this place is her ideal, a product of her strong desire to be left alone, free from intrusion.

Intruders do make it through to Liga’s place of safety, however. In the parallel world from which she has escaped, an annual festival is held where the strongest and most eligible young men of the village are stitched up in bear suits and set loose upon the town to kiss and chase the women. It is a day of release from the oppressive social mores which condemn women who exhibit any sexual independence. On this day, the women can behave as rampantly as they wish. Davit Ramstrong is a shy, sweet youth who feels ambivalently about his role as bear. But as he runs his inhibitions fade, and he feels charged with the bestial freedom afforded him by the anonymity of his costume. A careless stumble causes him to fall and hit his head. He awakes in a clearing that is familiar, yet changed. He has entered Liga’s place and spends a long time with her and her daughters, like a stray who becomes a beloved pet.

Lanagan writes these sections with great delicacy of feeling. She picks up on the non-verbal affection that people can feel for animals, the inarticulate companionship that also draws upon deeper parts of the human psyche. As in many fairy tales, the bears in the novel symbolise a powerful male presence that is not always malevolent, but driven by desires and impulses that are both attractive and destructive to women. They represent both protection and brutality.

Strong echoes of the Brothers Grimm tale Snow White and Rose Red are everywhere in this novel, even in its title. In the edition of the story that I have read, the greedy dwarf refers to the sisters as ‘tender morsels’ in a desperate attempt to lure the bear to eat them instead of him. The plot follows the traditional tale closely, but Lanagan is not content simply to write a clever allegory or an ironic pastiche. Her novel is visceral and frightening. Part of this is because of her witty and skilful use of language. Tender Morsels is full of vernacular phrases and words which are rooted in English and are therefore familiar, but which can also be elusive in their meaning. Lanagan employs her unusual lexicon to great effect to intrigue readers or to shut them out as foreigners whenever she pleases. This sense that you know the place and the culture, but that it is utterly strange and confronting, never fades as Liga and Branza leave their safe place to return to the ‘real’ world in search of the runaway, Urdda.

Lanagan revels in the magic and mystery that the genre allows, and is fearless in her descriptions of the violence and cruelty of which humans and animals are capable. She is interested in examining the morality of her characters’ actions and motivations, but does so with a cool eye, not encouraging easy conclusions. Many ideas are woven through Tender Morsels, but they are characteristically presented in a flash, almost peripherally, as the plot draws you on. These ideas about femininity and masculinity, sexuality and passivity, parenthood and childhood, are big and potentially cumbersome, but in Lanagan’s hands they are flinty, sparking connections that remain with you long after you finish reading.

Comments powered by CComment