- Free Article: No

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The great ocean of truth

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text: Richard Holmes’s aim in this remarkable book is to set aside the notion that ‘Romanticism as a cultural force is generally regarded as intensely hostile to science, its ideal of subjectivity eternally opposed to that of scientific objectivity’, replacing it with the notion of wonder, uniting once mutually exclusive terms, so that ‘there is Romantic science in the same sense that there is Romantic poetry, and often for the same enduring reasons’.

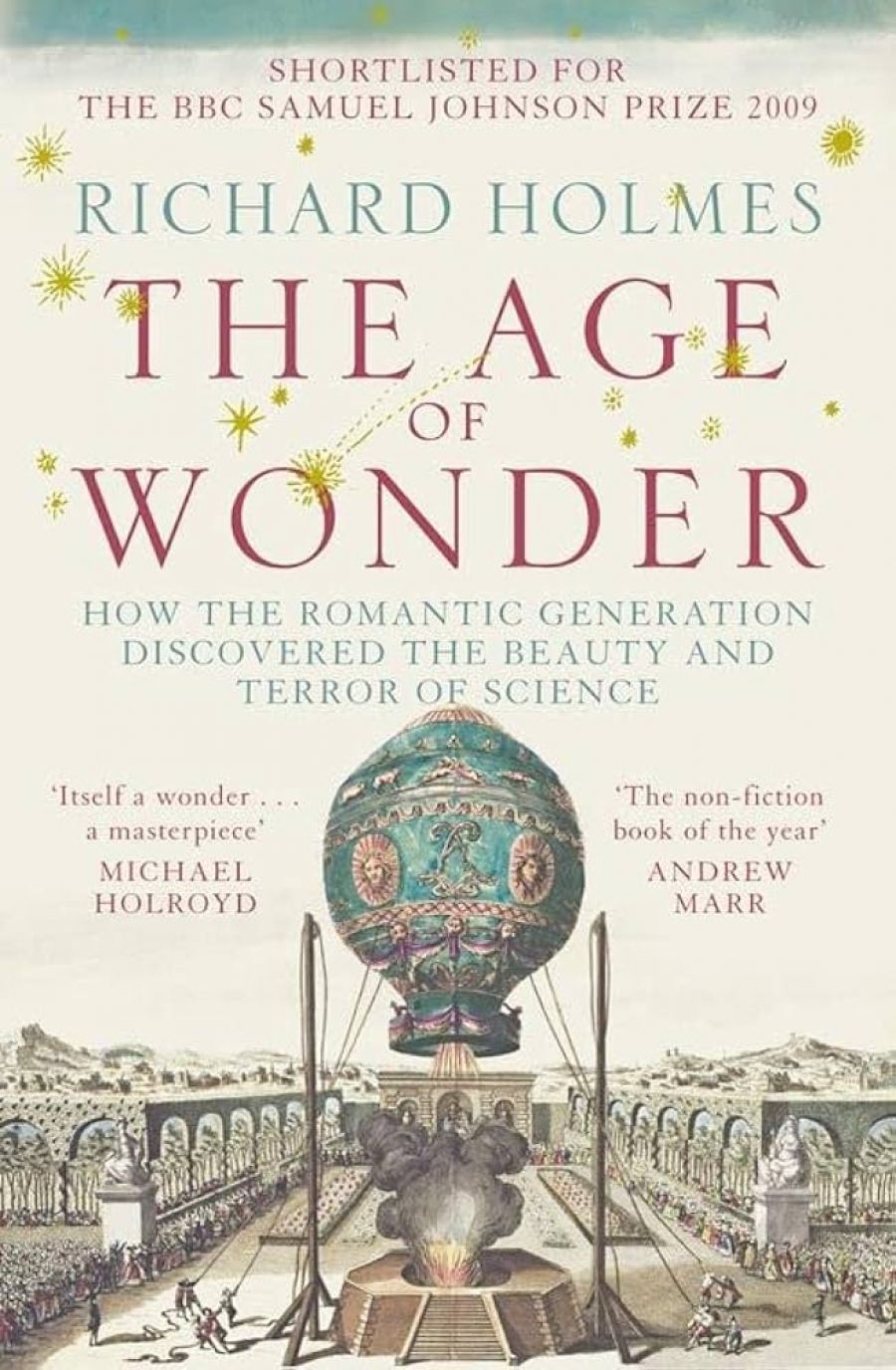

- Book 1 Title: The Age Of Wonder

- Book 1 Subtitle: How the romantic generation discovered the beauty and terror of science

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $59.99 hb, 553 pp

Holmes sees the Romantic science revolution as lasting barely two generations and dominated by two almost diametrically opposed lives: the astronomer William Herschel and the chemist Humphry Davy. He describes The Age of Wonder as ‘a relay race of scientific stories’ that explores a larger historical narrative framed by James Cook’s round-the-world expedition on board the Endeavour, which began in 1768, and Charles Darwin’s voyage to the Galapagos on the Beagle, which began in 1831. Indeed, the exploratory voyage emerges as the central and defining metaphor of Romantic science, recalling Wordsworth’s depiction of Newton as ‘a haunted and restless Romantic traveller’, ‘… a Mind for ever / Voyaging through strange seas of Thought, alone’.

It is the botanist Joseph Banks who links the stories, serving both as chorus figure and a scientific Virgil. He first appears as a twenty-six year old, ‘tall … well-built, with an appealing bramble of dark curls’. By temperament he is ‘cheerful, confident and adventurous: a true child of the Enlightenment’. He had, as well, ‘thoughtful eyes and, at moments, a certain brooding intensity: a premonition of a quite different sensibility, the dreaming inwardness of Romanticism’. Even before the Endeavour began its three months stay at Tahiti, Banks had been told it was ‘the location of Paradise … a wonderful idea, although he did not quite believe it’.

Although Cook named his crew’s Tahiti base ‘Fort Venus’ after the transit they were observing, many of them saw the name differently, more in line with the earlier French crew that named their base La Nouvelle Cythère, the new island of love, the sexual utopia. Bank’s Endeavour Journal records an amorous party in which he avoided looking at the Tahitian queen next to whom he sat (‘ugly enough in conscience’), preferring a girl ‘with fire in her eyes and white hibiscus in her hair’, and loading her ‘with bead necklaces and every compliment he could manage’ before the party broke up when Solander ‘had a snuff-box picked from his pocket’ and a fellow officer ‘lost a pair of opera glasses’. Holmes characteristically observes: ‘It is not explained why he had brought opera glasses ashore in the first place.’

Banks was the only member of Cook’s party who learnt a basic Tahitian vocabulary or sought to understand their society. He told himself that his ‘intentions were as much botanical as amorous and that no moral code was seriously infringed’. Gradually, he was drawn into the study of Tahitian society, the ‘Enlightenment Botanist, the aristocratic collector and classifier’ becoming an ethnologist, ‘more and more sympathetically involved with another community … trying to understand Paradise’. He also became the first recorded European to witness surfing. ‘The Tahitians did it for the sheer inexhaustible delight of the thing.’ One wonders if Robert Drewe knew that Banks had preceded him.

There is a liveliness in Holmes’s prose that often merges with witticism. Noting that Cook’s crew spent much time in bargaining for sexual favours, he observes that ‘the basic currency was any kind of usable metal object: there was no need for gold or silver or trinkets. Among the able seamen, the initial going rate was one ship’s nail for one ordinary f–k, but hyper inflation soon set in.’

In a footnote, Holmes comments that Banks’s unpublished Endeavour Journal was ‘one of the great masterpieces of Romanticism … as mysterious in its own way as Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” … as an account of a sacred place that has been lost’. Tahiti was ‘literally a Paradise Lost, in the sense that venereal disease, alcohol and Christianity had combined in the early nineteenth century to destroy the traditional social structures of Tahiti and to transform its “pagan” innocence forever’.

In 1778 Banks became president of the Royal Society and his interactions with, especially, William Herschel and Humphry Davy created the distinctive British science that Thomas Carlyle declared to have ended in 1829 (the year of Davy’s death), with the demise of Romanticism and the relentless arrival of the Age of Machinery.

Herschel was first sighted in Bath in 1779: ‘tall and well-dressed … his hair powdered … clearly an eccentric … with a strong German accent and no manservant accompanying him.’ More remarkable was his seven-foot long reflector telescope, ‘mounted on an ingenious folding wooden frame … evidently home-made’. A talented musician and obsessive astronomer, he was soon joined by his sister Caroline. Barely five feet tall, scarred by smallpox at five and typhus at seven, and treated contemptibly by her family, she forsook a career as an opera singer in order to support devotedly William’s obsessive astronomical work, in one sixteen-hour session putting small pieces of food in his mouth ‘like a mother bird feeding a demented nestling’.

In later years, she became the world’s first female astronomer, discovering two comets and in some ways rivalling William’s achievement in discovering a new planet, Uranus, on 13 March 1781, an event hailed as the first great success of Banks’s presidency; it became the symbol of the new, pioneering discoveries of Romantic science. Concepts such as ‘deep space’, ‘light years’ and a world ‘beyond the heavens’ challenged religious orthodoxies predicated upon creation’s having taken place only 6000 years ago. Herschel’s claims that many distant stars had ‘ceased to exist millions of years ago’ and that the night sky was ‘a shallow landscape that was not there at all … it was full of ghosts’, reminded the poet Thomas Campbell of Newton’s observation as a child picking up sea shells: ‘the great ocean of truth lay before him.’ One wonders what the forty per cent of recently surveyed Americans who still thought the world was created 6000 years ago would make of all this.

Holmes interrupts his account of the Herschels’ lives with a witty and insightful digression upon ballooning, focusing not only upon the science underpinning it but also on the perennial English jealousy of French scientists. America’s ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin, had advised the sceptical Banks of the new phenomenon, but Banks doubted its technological application. Some likened balloonists to Icarus; others, like the conservative Gentleman’s Magazine, declared it to be ‘the most astonishing discovery made perhaps since the Creation’. George III even offered to finance British experiments. But the unforgettable image was that of the actress, Mrs Sage, ‘renowned for her Junoesque figure and clad in a low-cut silk dress, presumably designed to reduce wind resistance’, on a spectacular out-of-control flight over Hyde Park in Lunardi’s balloon in June 1785.

When Banks met the small, volatile twenty-one-year-old Davy, the self-taught chemist spoke English with a Cornish accent and French with a Breton accent. Despite never having been abroad, he was up to date with French chemistry and ‘gratifyingly critical of Lavoisier’s work’. Solitary but an incorrigible flirt, enamoured of high society but mocked behind his back as a provincial, Davy would later ascribe his love of science to his fascination with storytelling. In 1797 Davy became suddenly fascinated with chemistry, the old alchemy having at last been replaced by true scientific experiments. Davy’s extraordinary work with nitrous oxide, driven partly by the impact upon him of his father’s death after a major stroke, also resulted in some appalling poetry, nonetheless containing precise physiological information.

In his lifetime, Davy saw chemistry join astronomy and botany as the most popular and accessible forms of modern science for amateurs, and as opening the next doorway into the ‘intelligent design’ of the universe. His own achievements as a chemist, and as the inventor of the safety lamps that transformed work in coal mines, saw him become president of the Royal Society, unopposed, in November 1820. But Holmes’s account of his life, his love for Jane Apreece, later Lady Davy, and his identification of the most exciting fields for new research as astronomy, polar exploration, the physics of heat and light, electricity and magnetism and geology, and the physiology of plants and animals, is most remarkable for its insights into the astonishing impact of Romantic science upon the literary world and the revolution it created insofar as the nature and scope of the literary and artistic imagination are concerned.

The Age of Wonder is an immensely readable, superbly informed masterpiece by the best biographer of literature, and now of science, that I have read. Faint praise is wholly inappropriate for such a book.

Comments powered by CComment