- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The importance of being Kenneth

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What if Kenneth Myer, not Sir John Kerr, had been Australia’s governor-general in 1975? There would still have been storms in Canberra, but no intervention, no Dismissal. Readers of Sue Ebury’s fascinating biography of Myer (1921–92) may be tempted to play the ‘what if’ game, speculating on how Gough Whitlam might have used a full second term as prime minister.

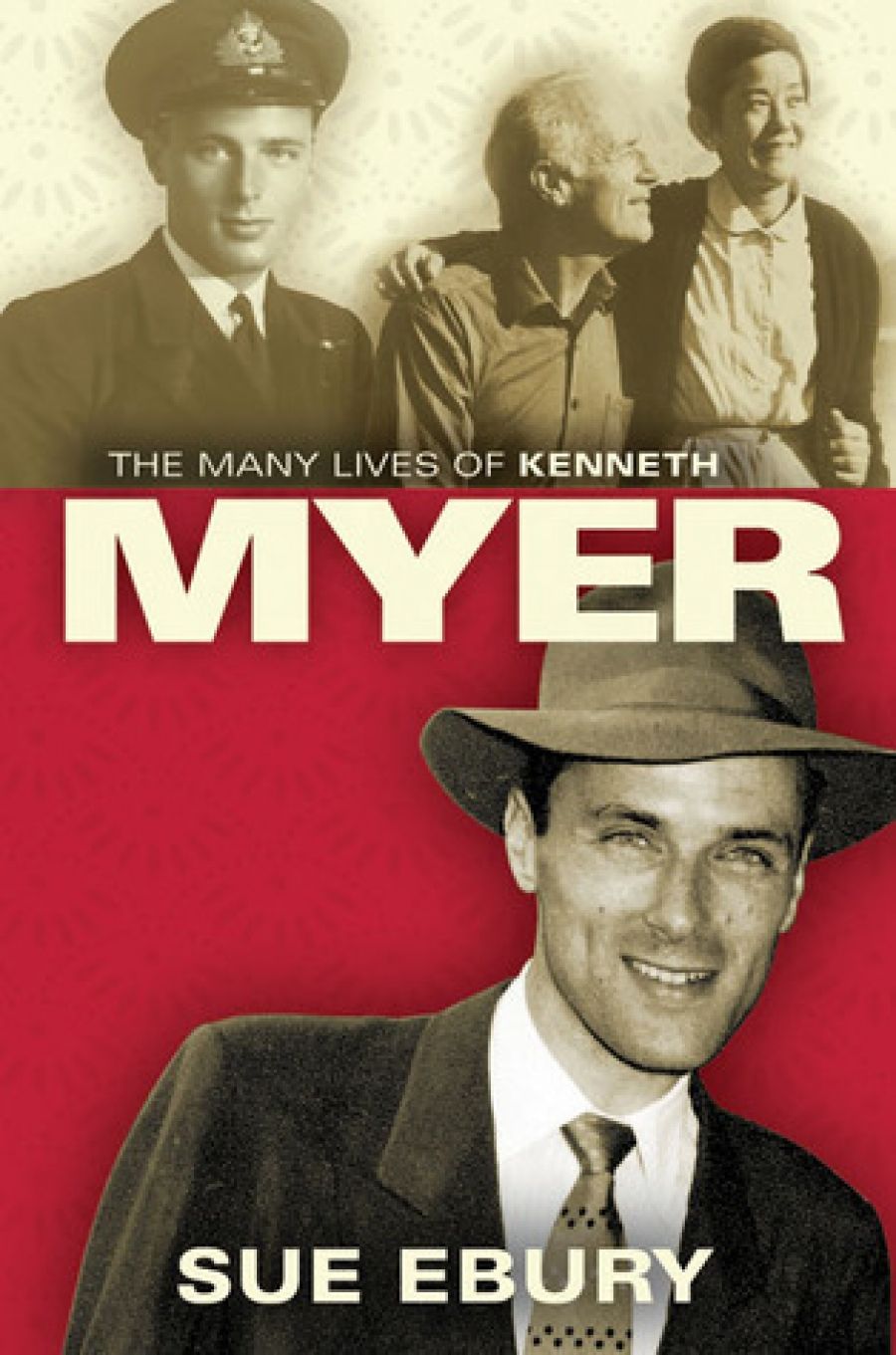

- Book 1 Title: The Many Lives of Kenneth Myer

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah, $59.99 hb, 621 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Ebury tells the story of Whitlam’s offer and reveals why Myer refused it. Myer told Whitlam that his wife Prue wanted to continue her academic career, that his teenage children would be unsettled and unhappy at Yarralumla, and that at the age of fifty-two he did not want the role of governor-general to close off other possibilities. What could there be left to do, once you completed a term in that high ceremonial office? But the real reason was his relationship with Yasuko Hiraoka, the Japanese woman, half his age, whom he would later marry. A governor-general’s divorce while in office was unthinkable. Yasuko’s nationality made it worse. Nearly thirty years after the end of the war, anti-Japanese feeling had abated considerably, but not enough to make Yasuko acceptable in the role of governor-general’s wife. Myer had met her while on long service leave in Japan, when he engaged her to teach him the language. He was already in love with Japan, and Yasuko embodied its mystery and cultural difference. She was tiny and gentle, and she thought he was ‘important’ – something he always doubted.

When Whitlam’s invitation came in 1973, Myer was a considerable figure in Australian public life. As the elder son of Sidney Myer, founder of Melbourne’s most famous retail store, he had used his money and influence in a number of public causes. He shocked conservative friends by signing the ‘It’s Time’ letter in the Age which gave Whitlam a considerable boost just before the 1972 federal elections. This intervention in politics was seen as an affront by Myer’s friends in the Melbourne Establishment. It also transgressed the policy of Myer management. There were angry telegrams and letters from all sides. A New South Wales Liberal parliamentarian announced that he would appeal to all members of the Coalition parties to boycott the store. The Myer board of directors passed a censure motion, reminding Ken Myer that he could not take a public personal stand on politics without involving the company. As executive chair-man of the board, and the store’s public face in the com-munity, he was not a free man.

That question of his individual freedom plagued Myer’s life. Ebury depicts a gifted but deeply troubled man with an ambivalent attitude towards his vast inheritance, and towards the father whose huge achievement he could never hope to match.

Sidney Myer (1878–1934) was the archetypal self-made man: a Russian-Jewish immigrant who started his Australian life as an itinerant peddlar in country Victoria. A wheelbarrow load of goods led to the vast Myer store in central Melbourne, with its many offshoots. This empire became a burden to his son.

Ebury sees the early death of Sidney Myer as the defining moment in his son’s life. At the age of thirteen, Ken was a small, lonely figure as chief mourner in his father’s funeral procession. The year was 1934, the Depression reaching its lowest point. Boarding at Geelong Grammar, Ken was not able to forget the responsibilities of wealth. The headmaster, James Darling, an Englishman who had joined the Labor Club at Oxford, was a Christian socialist with a strong sense of mission. By involving his privileged students in schemes like the Geelong Boys’ Employment Service, he made sure that they had a glimpse of what it was like to live in poverty.

Ken Myer never had the chance to choose his own future; the Myer Emporium was always there, waiting to test him. His mother considered sending him to Oxford, but when the war broke out in Europe in 1939, she decided on a university in the United States, where the Myer family had close connections. Princeton was a bad choice. The anti-Semitism which Ken had not felt at Geelong Grammar was endemic in this Ivy League institution, which admitted a few Jewish students, on a fixed quota. With his Jewish father and his Church of England mother, Ken was insecure and defensive at Princeton. The experience did, however, widen his horizons. He heard Albert Einstein lecture; he made friends with students from Europe; he took part in a survey of housing conditions of black families in the university town.

Suddenly, his imperious mother, Merlyn Myer, summoned Ken home from Princeton. He joined the navy and served through the war. Still the Myer heritage loomed. He did not complete a postwar commerce degree at the University of Melbourne, but it was there that he met his future wife Prudence Boyd, an able and ambitious law student. Marriage and children halted Prue’s career. Being a rich man’s wife was not enough; she wanted to do something on her own account, and eventually she enrolled for a diploma of education. And at about the time that her new career became absorbing, Ken went to Japan and met Yasuko.

Ebury’s interpretation of Myer’s difficult temperament is persuasive. Lack of confidence in his own abilities and a sense of obligation, combined with energy and intellectual curiosity, made him a generous patron of other people’s causes. He had nearly all life’s gifts: good looks, charm and intelligence, as well as riches, but he suffered from depression, and could be icy and unreasonable. He was a remote father and a difficult husband, envious of his first wife’s career. One weakness in the emotional history comes from Ebury’s failure to see Yasuko clearly; she remains unrealised, even sentimentalised.

The city store, centre of the Myer inheritance, came with a high price. Under the terms of his father’s will, Ken had to take an active part in its management by the time he was thirty, or else forfeit his elder son’s portion. Having lost six years in war service, Ken had little time to look around and develop his own talents. That enforced decision left him with a sense of failure.

Ken Myer used his talents on many public and philanthropic causes. As chairman of the ABC, his impetuous style and lack of negotiating skills were ultimately disastrous, but the National Library, CSIRO and the Howard Florey Institute owe him a great deal, as do countless Australians who benefit from the Myer Foundation, to which he left the bulk of his estate. Being blackballed in 1953 by the Melbourne Club was a reminder of his outsider’s status (his brother, ‘Bails’ Myer, was similarly rejected in 1970), but this experience did not lessen his generosity to the whole community.

Myer’s wide-ranging interests are a problem for his biographer, whose painstaking research is at times distractingly over-detailed. There is just too much to take in: too many activities, too many minor characters, often simplified in a single phrase or two. But, on the whole, this is an impressive work by the author of the acclaimed biography of ‘Weary’ Dunlop (1994). You might want to skip a few board meetings, but the central narrative is compelling, the tone cool and fair-minded, the context thoughtfully realised.

Comments powered by CComment