- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poems

- Custom Article Title: The importance of elsewhere

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The importance of elsewhere

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

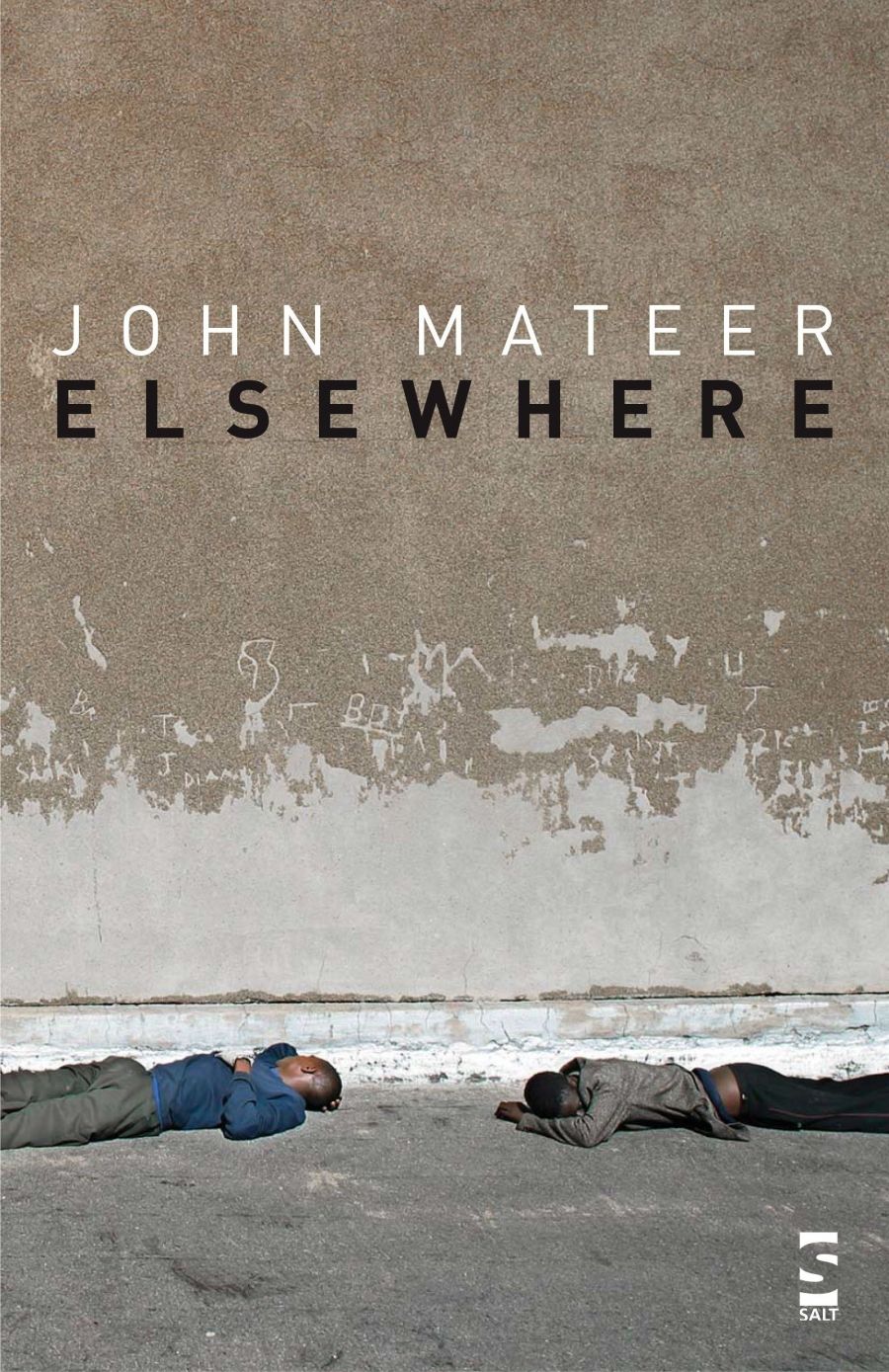

John Mateer’s Elsewhere is a collection of poems from elsewhere – other small-press publications – and about elsewhere. The book is divided into three parts: ‘Azania’, which documents Mateer’s return to his homeland, South Africa; ‘Medan and Zipangu’, which contains poems inspired by travels in Asia; and ‘Americas’, which takes the United States and Mexico as its subjects. In ‘Uit Mantra’, one of the poems in the collection, Mateer describes the poet as ‘another name for emptiness’. As he traverses the various landscapes and cultures that inspire him, Mateer acts as a cipher for both the tangible particularities of experience – landscapes, history, people – as well as the unsayable and the unsaid – the repressed, metaphysical and hallucinatory.

- Book 1 Title: Elsewhere

- Book 1 Biblio: Salt, $27.95 pb, 136 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The first section of the book is the most powerful. The South African poems convey the traumascapes of a devastated world in which the poet feels unavoidably implicated. As Mateer writes in ‘My Europe’, he has ‘inherited nostalgia for this, my parents’ birthplace, my / Europe, the mother-city’. These poems, though, derive their strength not from sentimentality but from the rawness of lucid observation and emotional honesty. ‘Johannesburg’, for example, describes the poet’s arrival at the airport. He sees a familiar banner for the diamond industry, ‘a void, a blackhole / hauling everything’. He observes ‘billboards warning of AIDS and hotels / fronted-up like Wild West towns’ and ‘black Africans in balaclavas and beanies, curled up under blankets / on the open trays of bakkies’. The poet wants to say ‘It hasn’t changed, but the pain’s unfocus / was like that one homeless man’s standing away from his huge / shadow in the warming suburban wall’.

Mateer, being white, also gives acute and unnerving expression to feelings of guilt. In ‘Ethekweni’, he wonders how he dared shake the hand of a black poet: ‘I look at my hand on the table between us: a pale, grotesque thing.’ In the extraordinary ‘Valkenburg’, the poet relates a nightmare in which ‘Apartheid politicians’ have infected him:

… Could be they’ve

fetched the big ants from the graveyard,

dried and mixed them and sent them

to me with their evil spirit. Could be

they awaken and speak through my mouth

using my lungs, sitting bloated in my belly

like fed tapeworms, like eaten tongues …

I speak: I’m vomiting. These surges of bile

Tear from beyond me. Their silence shouting

my throat hoarse is the Devil’s voice.

The horrors of apartheid South Africa are repeatedly connected in Mateer’s poems to the possibility of other repressed things. ‘Dark Horse’, a poem dedicated to J.M. Coetzee – described as the ‘allegorical novelist who is said not to speak’ – suggests that care needs to be taken with what is given voice: ‘Beware of those bearing grief in comprehensible words. / Beware of your mouths.’ In many of the poems in ‘Azania’, Mateer represents what he sees in apparently straightforward as well as striking ways, but there is always an allusion to something else. In ‘Unbeliever’, a snapshot of a gathering marred by the utterance of an unnamed word, the unspeakable appears to involve the awfulness of apartheid itself. In other poems, such as ‘The Elephant Graveyard’, the mystery lies in the abominable otherness of life. In this sequence of poems, which describes the culling of elephants, the vultures make ‘hallucinations’ of our lives.

The Asian poems in the second section are less grounded in the poet’s history, and the unspeakable takes on a more exotic and metaphysical aspect. The poems here also tend to be more imagistic, which Mateer often explicitly connects not only to tourism and photography but also to the tragedy of transience. In poems such as ‘Be Careful’, for instance, the poet conveys the self ‘in the senseless universe’ as ‘nothing but a photographic flaring’.

The poems about Asia, more troublingly, are also often focused on femininity, another familiar trope when it comes to poems about Asia. Poems such as ‘No woman’ seem to evidence a misogyny as striking as that of the Symbolists: ‘A photon ricochets through the wilderness of her skull. // Woman as cancer. // Her breath on any face is carbon monoxide. // Her flesh, haunting the world like a porno-star’s, // is space.’

The final and shortest section of the book, ‘Americas’, is refreshingly ironic. America is depicted as a world of patriotic simulacra where, as we read in ‘Two Faces of the New World,’ ‘the whole of Chicago is musical theatre’. ‘Empire,’ one of the best of the American poems, portrays a football game as a Roman spectacle, at the end of which ‘the eagle has sprung to the Astroturf, / has run to the centre of the field and has proclaimed, / by stabbing his flagpole into the ground, / that we have landed not only here but also on the moon’. The poems about Mexico are equally entertaining, acknowledging the way in which the poet’s experience in Mexico is mediated by myth and Hollywood. ‘That I Might be Mexican …’, for instance, refers to crossing ‘the Rio Grande hidden under a black sombrero’ and relates how ‘my heart, slimy and erratic, is held high / in the fist of a cartoon Aztec’.

Mateer is a poet who speaks, after a line in ‘In the Valley of a Thousand Hills’, with his ‘mouth opened to what hijacks sound’. Suffering, the transience of life and the madness of empire are among the subjects of the poems that make up this interesting and important collection by a well-travelled Australian poet.

Comments powered by CComment