- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: Pornarama

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Pornarama

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Pornification, The Porn Report and Princesses and Pornstars are three recent entries into the burgeoning academic field known as ‘porn studies’. All three books aim to move beyond the simplistic ‘for’ and ‘against’ arguments that have traditionally surrounded pornography. Instead, each text explores the challenges and complexities of living in a world where sexually explicit material is more prevalent than ever before.

- Book 1 Title: The Porn Report

- Book 1 Biblio: MUP, $34.95 pb, 224 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

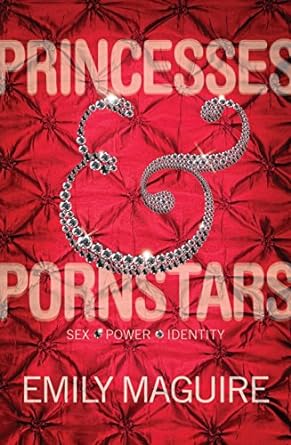

- Book 2 Title: Princesses and Pornstars

- Book 2 Subtitle: Sex, Power, Identity

- Book 2 Biblio: Text, $32.95 pb, 210 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 3 Title: Pornification

- Book 3 Subtitle: Sex and sexuality in media culture

- Book 3 Biblio: Berg, $29.95 pb, 204 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

Pornification is perhaps the broadest-ranging of the three books. The title refers to ‘the increased visibility of … pornographies, and the blurring of boundaries between the pornographic and the mainstream’. The text comprises a series of essays written by academic researchers from a variety of disciplines. These researchers address the way that the production and consumption of pornography has intersected with factors such as race, sexuality, technology and global capitalism.

In the first chapter, the editors (Susanna Paasonen, Kaarina Nikunen and Laura Saarenmaa) argue against ‘any simplified generalizations concerning pornography and its status in the contemporary mediascape’. As they put it, ‘what pornography means and what is understood as pornification internationally is not reducible to some “general” framework’. Thus, the contributors to Pornification focus on various modes of pornographic cultural production that have arisen in a range of countries. They draw information from traditionally ‘scholarly’ outlets (for example, refereed journal articles), as well as websites, media articles and magazines such as Adult Video News.

The essays are (mostly) engagingly written and well researched. I particularly enjoyed Jenny Kangasvuo’s piece on bisexuality and gender difference in ‘hardcore’ pornographic magazines published in Finland. Kangasvuo astutely argues that ‘female sexuality is open to renaming’ in these magazines, but the same cannot be argued for men. This is because, in a world where sexism and heterosexism still hold considerable sway, ‘[m]ale bisexuality and homosexuality lie frighteningly close to each other’. Also, Mireille Miller-Young brilliantly analyses representations of interracial desire in the video pornography that flourished in America during the 1980s. Miller-Young argues that, while the sexual activity depicted in these videos may have seemed ‘transgressive’ to some viewers, they still frequently endorsed antiquated stereotypes ‘of black women as hypersexual, hyper-available, deviant and degraded’. The author condemns these stereotypes, and encourages her readers to rethink ‘the politics of cross-racial/gender/sexual desire’.

However, Miller-Young is one of the few contributors to Pornification who overtly criticises pornography. Many other contributors seem unwilling to do this. For example, in his analysis of contemporary British gay male culture, Sharif Mowlabocus argues that to ‘wholly condemn’ pornography – even that which is not ‘politically correct’ – means that we ‘ignore the complex and subtle bond’ that some consumers have developed with this material. Writers such as Mowlabocus are undoubtedly wary of offending or denigrating these consumers. They are also perhaps wary of aligning with the rhetoric of anti-pornography feminists such as Andrea Dworkin. These feminists are dismissed by the editors in familiar libertarian terms. Dworkin and her supporters are, we are informed in the first chapter, ‘gynocentric’, ‘ideological’ and supportive of ‘censorship’.

Yet arguments about pornography are always going to generate varied and often highly emotional responses, no matter what stance a writer might take on this issue. I would instead argue (following theorists such as Dworkin) that it is politically necessary to criticise sexually explicit materials that eroticise misogyny and other forms of oppression, even if such criticisms might be displeasing to the men and women who consume this material. The failure of some contributors to Pornification to do this means that the text’s overall analysis of pornography is not as nuanced as it could have been.

The Porn Report covers similar ground to Pornification, though it specifically addresses the consumption of pornography. The text emerged from a three-year Australian Research Council grant entitled ‘Understanding Pornography in Australia’. Throughout the book, the authors (all well-known and prolific researchers in the fields of media and cultural studies) draw from interviews with ‘more than 1000 porn consumers’ throughout Australia to ascertain ‘what kind of pornography they like, what their social and political attitudes are and what role they think porn plays in their lives and their relationships’.

Alan McKee, Katherine Albury and Catharine Lumby begin by dispelling the myth that there is a ‘typical porn user’. This typical user is generally thought to be a ‘sad, lonely man’ who is ‘addicted to the internet’ and ‘can’t get a girlfriend’. However, the authors point out that, according to their findings, pornography is actually used by a diverse range of men and women. Their interviewees vary according to a number of factors, including age, sexual orientation, political and religious affiliation, and geographical location. Many of them are in stable relationships, and they consume pornographic materials alongside a range of other non-sexually explicit materials (for example, novels and films).

Additionally, throughout The Porn Report, the authors describe the various debates about censorship that have taken place throughout Australian history, as well as the perceived negative impact of pornography upon its consumers (one chapter is humorously titled ‘Does Pornography Cause Masturbation?’). They consider the ways in which children have both consumed and been used within pornographic materials. The authors also interview men and women who have produced their own pornography (referred to here as ‘DIY Porn’).

There are many fine moments throughout the book. Overall, I found the chapter on child pornography to be the most engaging. This is an emotive subject, as the authors rightly point out, and they tackle it in a remarkably sensitive and balanced manner. They argue that ‘[m]aking or using child pornography is … one of the worst crimes’, and describe the legal regulation of this material in Australia. The authors suggest ways that parents can protect children from ‘online adult pornography’ and ‘cyber-stalkers’. They also debunk the still popular stereotype of the paedophile as an ‘anti-social and pathologically inadequate drifter’.

At times, the authors of The Porn Report echo the dismissive attitude that was displayed by the editors of Pornification towards feminists such as Dworkin. In doing this, they detract from the sophistication of their text. For instance, McKee, Albury and Lumby seem to suggest that pornography users are representative of what they, somewhat cryptically, term the ‘average Australian’, but that anti-pornography feminists are not. This suggestion is problematic for two reasons. Firstly, some of the insights made by anti-pornography feminists (namely those regarding the potentially exploitative nature of pornographic film-making) are endorsed or at least commented upon favourably at different points in The Porn Report. Also, the aforementioned suggestion would appear to contradict an argument that the authors make early in the text: that there is no one specific viewpoint on pornography in Australia.

Princesses and Pornstars explores the advantages and disadvantages faced by young women in an increasingly ‘pornified’ society. The author, Sydney-based writer Emily Maguire, argues that while this current era is considerably more sexually permissive than earlier ones, the same restrictive gender roles are intact. Women are still being judged according to a ‘bipolar model of gender’, in which they can ‘have orgasms or respect … be independent or adored’.

Throughout the text, Maguire discusses women’s mixed responses to pornography. She also addresses issues such as marriage, body image, sexual violence and motherhood. Maguire’s brand of feminism is a distinctly open-minded and inclusive one. She argues that women and men ‘need to act together to tackle sexism if we truly want to be free as individuals’. In doing this, she points out that ‘[w]e need to shout about the fact that gender roles are constructs’ and acknowledge that ‘people should not be defined solely by their sex’.

Maguire’s writing style is lively and lucid, and her observational skills are sharp. This is particularly evident in her critique of the mainstream media’s tendency to herald all activities performed by women as being somehow empowering: ‘Women, if the mainstream media are to be believed, are becoming more powerful with every wax-strip, lap-dance, oven-scrub and baby bath.’ Similarly, she makes an excellent point about the potentially detrimental nature of the media’s emphasis on women’s ‘curves’: ‘how exactly does it help to tell thin girls (or fat girls for that matter) that men only love curves? Isn’t this replacing one ideal image with another?’

Also, and significantly, Maguire does not suggest that she is herself beyond patriarchal conditioning. Late in Princesses and Pornstars, for example, she admits that ‘despite knowing how misogynous and false the beauty ideals of mainstream media are, I continue to hate my appearance’. Such admissions might be seen as politically defeatist or, conversely, as instances of mindless navel-gazing. However, in making such admissions, Maguire admirably refuses to portray herself as being politically superior to her readers.

Maguire acknowledges early in the text that she is not ‘a spokesperson for the feminist movement’, and that Princesses and Pornstars reflects only one feminist viewpoint. Her book seems specifically aimed at ‘women and men of [her] generation’ – that is, in their late twenties to early thirties. Also, Maguire’s analysis seems to focus primarily on white, heterosexual and able-bodied women. This, in itself, represents a major limitation of the text. The reader is constantly led to wonder how the author’s insights might be applied to a woman who does not occupy this relatively privileged subject position. How might, say, an Aboriginal woman, a disabled woman or a middle-aged woman be affected by the beauty norms or the pornographic imagery that Maguire discusses?

Overall, the three books under review here provide useful and provocative accounts of life in an increasingly sexualised world. Each book does (as I have pointed out) have its flaws. Pornification and The Porn Report run into problems when they try to distance themselves from anti-pornography feminism, while the feminist viewpoint expressed within Princesses and Pornstars is restricted by the author’s privileged subject position. Ultimately, these texts still contain a range of important and thought-provoking observations about the relationship between sex, gender and representation in contemporary culture.

Comments powered by CComment