- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: Camels and stink bombs

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Camels and stink bombs

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

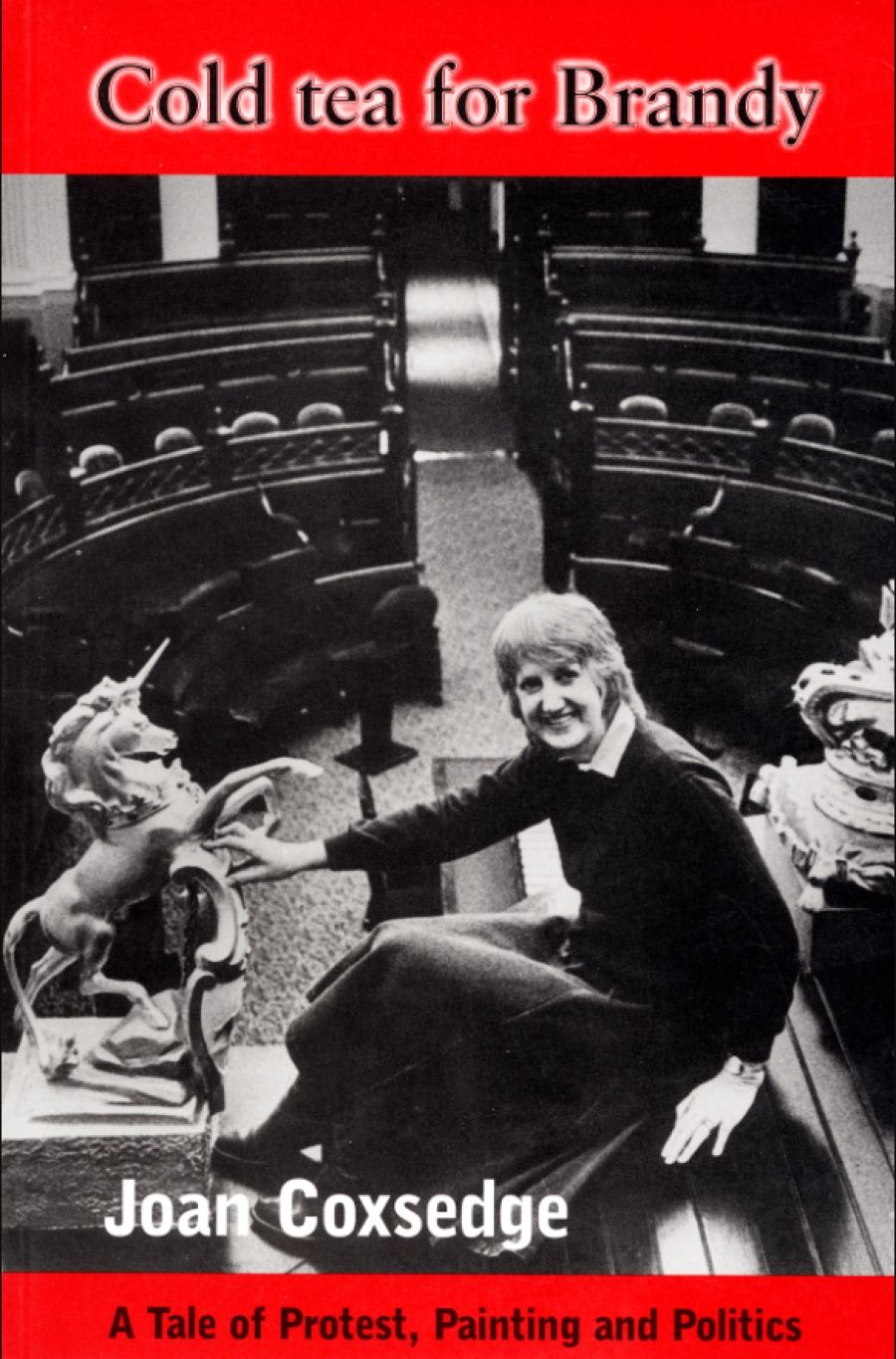

Now aged in her mid-seventies, the activist, artist and one-time parliamentarian Joan Coxsedge has penned her memoirs. Cold Tea for Brandy is as entertaining a read as her own varied life seems to have been. Decades of public advocacy, a firm – some would say a fixed – moral compass and an illustrator’s gift for precise impression have given Coxsedge a writing style to be admired. Her prose is brisk, simple, amusing and easy-going, laced with an old-fashioned Australian vernacular. Some readers may find the writing as anachronistic as the socialist beliefs that Coxsedge has so ardently espoused for decades. Still, the clarity of her writing flows organically from the that of her politics.

- Book 1 Title: Cold Tea for Brandy

- Book 1 Biblio: Vulcan Press, $39.95 pb, 431 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

That political life has indeed been significant, although it did not include high office. For a generation, Coxsedge stood at the forefront of many important and radical socio-political reform movements. Her first experience of public protest occurred during the Vietnam War, when she was a founding member both of the Melbourne branch of Save Our Sons (SOS) and of the Congress for International Cooperation and Disarmament. Representing the latter, she successfully shut down an American–Australian Association dinner at the Southern Cross Hotel with a stink bomb. The ramifications of her anti-conscription activities with SOS were more serious: a jail term of ten days for wilful trespass (she was advising conscripts of their legal rights in the premises of the Department of Labor and National Service). Undeterred, Coxsedge went on to co-found the Committee for the Abolition of Political Police, which brought her into direct conflict with ASIO, state police special branches and various political-legal forces, which declined to share the committee’s dream of a society free of secret police.

Coxsedge was just as concerned with civic amenity and the preservation of public heritage, and lent her fine drawing skills and ink pictures – many of which adorn the book – to the ‘Green Bans’ campaign of the early 1970s, which paired community action groups across the country with the Builders Labourers’ Federation, to oppose development that threatened inner-urban green wedges and historic buildings.

Later, Coxsedge was voted into the Legislative Council of the Victorian Parliament, one of two women to break through the glass ceiling of this resolutely conservative chamber. Her thirteen years in Parliament, as an ALP member representing inner suburbs of western Melbourne, failed to break her communalist spirit. But her determination to ‘ignore the internal power-plays [and] big business constituents’, and to put to government the cases of ‘those doing it tough’ brought her into irreconcilable conflict with the parliamentary, factional and administrative leadership of the party. Consequently, Cold Tea for Brandy stands, in part, as a record of the great internal struggle of the ALP, between pragmatic opportunism and social-democratic idealism.

An inaugural member of the Socialist Left faction, which opposed federal intervention in the Victorian branch of the party and Gough Whitlam’s extension of state aid to non-government schools, Coxsedge was drawn to the party more as a vehicle for the pursuit of social reform and justice, although she by no means discounted the value of industrial goals. But, like most adherents of the left, her experience of the ALP was one of dissatisfaction with Labor’s leading lights and the neo-liberal agenda they soldered onto the party.

The Cain government, of which she was a member, and the Hawke–Keating duumvirate particularly dismayed Coxsedge. They stand accused of adopting Liberal ‘reforms’ (she uses the word in its Orwellian sense), falling into a ‘bipartisan grovel’ before multinational businesses and creating a rift with the party’s working-class base.

For Coxsedge, the policy shift was the direct consequence of the rise to power of faction hacks in the post-Whitlam period, which has had a ‘devastating effect’ on the party, transforming it into a top-down organisation that acts contrary to the wishes of its rank and file. Similarly, Coxsedge decries the decline of manufacturing and working conditions, and the ‘stagnantly high’ unemployment rates that she associates with the neo-liberal economic policies of the last generation. Coxsedge is silent, however, on the international context for these changes. This is a problem, for it is, at the very least, questionable that Australia’s ‘financial controls’ prior to deregulation of the financial sector were ‘carefully constructed’, or that this small nation’s manufacturing base could continue to protect the pre-1983 wage levels she exalts in a rapidly globalising economy, behind a protective firewall of tariffs.

Coxsedge will invite fewer rebuttals in her commentary on her early life and her personal and professional struggles. Cold Tea for Brandy is a valuable historical document of the Depression-era Australia she was born into, and the stiflingly conservative 1950s and 1960s during which she became politicised. Her childhood in Melbourne’s west is movingly described: the stench from nearby soapworks; the quarantine of Victoria during a terrible outbreak of polio in 1937, during which some of her classmates died or were consigned to calipers and wheelchairs; and the eviction of the family from their home, in 1946, to make way for a returned serviceman. Less touching, but highly amusing, are her descriptions of postwar, ‘rural’ North Balwyn, where her young family settled. Initially, camels from a nearby wildlife sanctuary ‘were a familiar and fascinating sight as they solemnly swayed down the hill for drinks at the gum-tree lined creek’. Soon enough, however, the camels were moved out and replaced by ‘large dull houses’ inhabited by working-class Tories – ‘today’s “aspirationals”’ – and ‘entrenched conservatives whose houses were as boring as their politics’. Plus ça change.

Comments powered by CComment