- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: Words strain

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Words strain

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

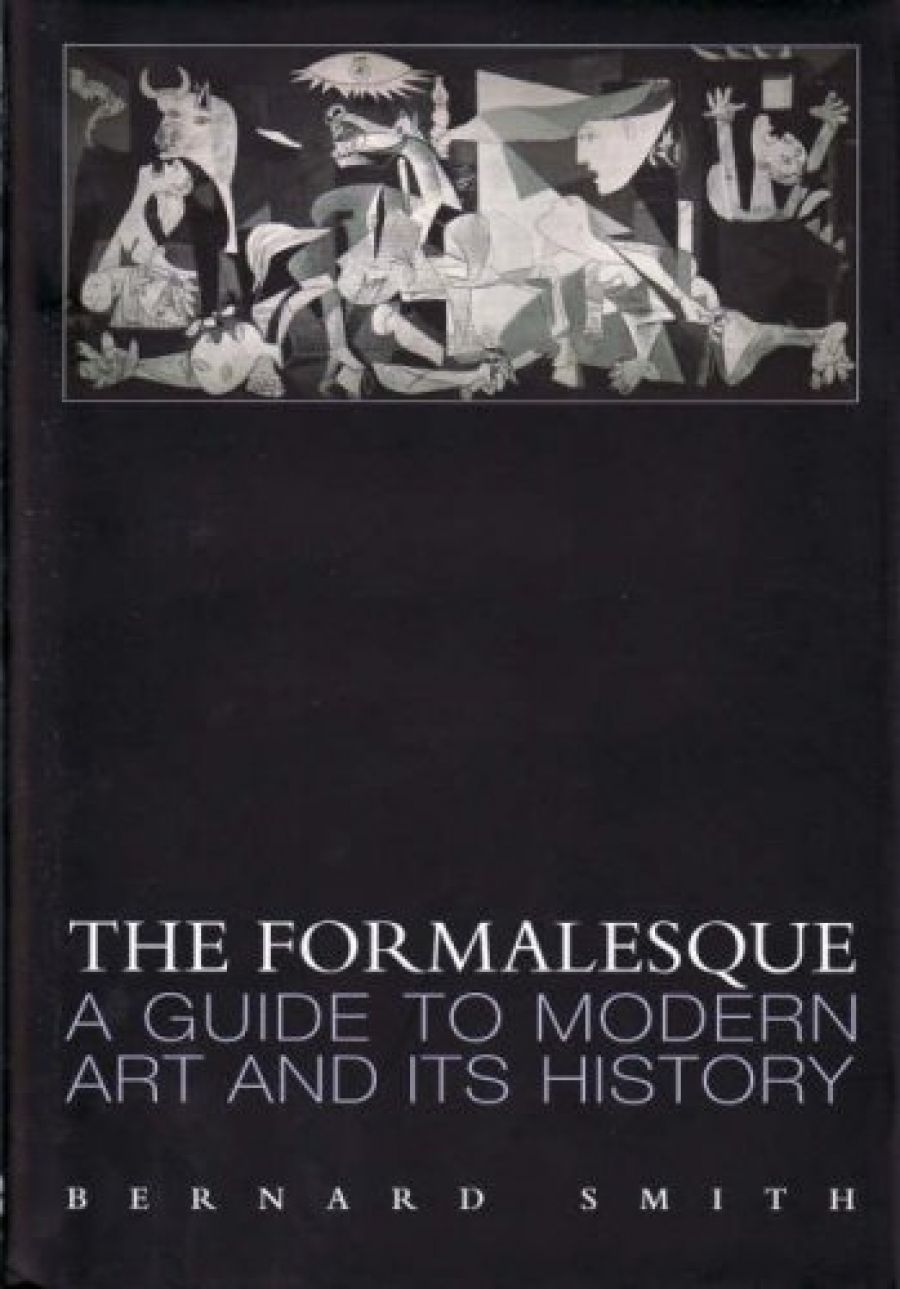

Bernard Smith’s new book, The Formalesque: A Guide to Modern Art and Its History is aimed directly at those school and university students who, he writes, ‘may need an introductory primer to the art history of the 20th century’. Although it offers a lucid and accessible survey of familiar territory, The Formalesque is by no means a straightforward textbook. Smith’s persuasive, even pugnacious style has remained remarkably undiminished by time (the author is now in his nineties and this, as he himself has said, will probably be his last book).

- Book 1 Title: The Formalesque

- Book 1 Subtitle: A guide to Modern Art and its History

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, $77 hb, 135 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Chapters 3 and 4 deal with, respectively, form, or ‘The Rise and Decline of the Formalesque Style’, and meaning, in which the story of art history is picked up again from Panofsky’s iconological method to what in the 1970s was called ‘The New Art History’. The chapter on form is central to the book as a whole, tracing as it does a history of what Smith calls ‘the Formalesque style’. This turns out to be what most people think of as ‘Modernism’ but, unlike other recent textbooks, is notable for its inclusiveness, despite its brevity. Smith rightly points out that

[a]part from the special case of the USA, the spread of the Formalesque style from its European base has not been considered in detail by art historians as an international phenomenon, although there is abundant evidence available in the many histories of the modern art of particular countries.

Smith’s epilogue closes the book with some comments on the limits of art history when faced with the contemporary: ‘It is when the party’s over that the art historians arrive and do what they can to understand why the newly-minted masterpieces were so admired in their own time and what they may still mean to us today’. (‘Contemporary art history’ is, of course, an oxymoron.)

The shadow of the Austrian art historian Ernst Gombrich looms larger than any other over Smith’s book. Gombrich’s positive appraisal of Smith’s previous work, Modernism’s History (1998), appears on the dust jacket, and the author’s debt to him is acknowledged in several places throughout the text. Gombrich is one of the only art historians to have adopted Smith’s neologism ‘The Formalesque’ (in the posthumously published The Preference for the Primitive, 2002).

Gombrich, however, almost never wrote about modern art. He was primarily interested in the Renaissance, and his most important contributions deal with the art and culture of that period. Over time, art-historical methods of analysis and interpretation have frequently been proven to be useful only insofar as they are capable of explicating the works of particular periods and places. Panofsky’s method is a case in point. It once seemed to offer the key to unravelling the ‘disguised symbolism’ of early Netherlandish paintings by Jan Van Eyck and others, but is next to useless when it comes to explicating the meaning(s) of Mondrian’s twentieth-century abstractions.

No matter. The central claim of Smith’s book is that we should abandon the term ‘Modernism’ in favour of ‘the Formalesque’, an argument that he also made in Modernism’s History. There are common-sense reasons to do so, including the fact that ‘modern’ has had a long history in the visual arts. Vasari, for example, uses the phrase maniera moderna to describe the art of what we now think of as the High Renaissance. According to Smith: ‘The problem we face here is that since the terms “post-modern” and “Post-modernism” came into current usage some thirty years ago, “Modernism” is still used to describe a kind of art that is no longer modern in the sense that it is no longer current.’ The advantage of ‘the Formalesque’ is that it emphasises what Smith considers to be ‘the dominance of form in 20th century art’.

This strikes me as more Greenbergian than Gombrichian. The American critic Clement Greenberg thought that the most important modern art was fundamentally about itself. For him, the ineluctable condition of painting, for example, was that it boils down to line and colour on a flat surface but that, in Modernism, these limitations were seen as productive ones. Greenberg’s formula may have value when it comes to certain kinds of modern art, but it leaves out so much that its broader utility is questionable. Apart from anything else, it seems to imply that the best art belongs, or should belong, to some perfumed realm of disinterested aesthetics, unconcerned with life as it is lived, as if art were some kind of sophisticated parlour game. Other writers, such as the German critic Peter Bürger, have emphasised the ‘social agency’ of modern art, especially those avant-garde movements (Soviet Constructivism, for example) that sought to effect change in the world and that refused the distinction between art and life.

Smith’s own allegiances in this debate are perhaps best revealed in his definition of ‘avant-garde’ in Chapter 1:

The pioneering or innovative writers, artists, etc. in a particular period’ (SOED, 1993). It originally meant the vanguard of an army and did not emerge in its present form until the early 20th century. It begs the question of course. It is for critics and historians to decide who were the pioneers in any given period, and it is in general use only for the pioneers of Modernism or, as I would say, the Formalesque. But there is no logical reason why it should not be used for the pioneers of any period if they are to be named.

There are, however, good reasons why ‘avant-garde’ should remain an historically specific concept. The term was actually first used to refer to radical or advanced social as well as artistic activity, which, oddly, Smith does not mention, despite his characteristic close attention to words and their nuances of meaning. In fact, more often than not, it is social avant-gardism that is given priority in the earliest recorded uses of ‘avant-garde’, such as in the work of the French utopian socialist Henri de Saint-Simon, writing in the 1830s. The modern artist who most completely embodies this idea was Gustave Courbet, who once flatly (but not in Greenberg’s sense) declared that ‘Realism is democracy in art’.

‘Words strain’, as Smith knows well – he quotes T.S. Eliot’s line at the beginning of Chapter 1 – and ‘the Formalesque’ has several undeniable virtues as an art-historical idea. However, in time it may prove no more adequate to the task of accounting for twentieth-century art than ‘Modernism’. In the end, all terms for ‘period styles’, such as they are, are probably hopelessly reductive, unless art really is a parlour game of little consequence.

Past and Present

Bernard Smith continues to publish in his nineties (he was born in 1916). Luke Morgan reviews his latest work, The Formalesque: A Guide to Modern Art and Its History (Macmillan), on page 19. Eighteen years ago, Jonathan Holmes welcomed a swag of reissues by Professor Smith. These included The Critic As Advocate: Selected Essays, 1941–1988. The full text of this review, published in October 1990 and titled ‘The Genesis, Exodus and Leviticus of Australian Painting’, appears on the ABR website. Here is an extract:

Given that Emeritus Professor Bernard Smith’s role in the visual arts in Australia has been so influential since the 1940s, it is particularly pleasing to see Oxford University Press continuing to republish his three great works of art historical scholarship and art criticism, Place, Taste and Tradition (1945), European Vision in the South Pacific (1960) and Australian Painting 1788–1960 (1962; 1971) […] OUP has also published an outstanding collection of essays covering over forty years of Bernard Smith’s critical writing, The Critic As Advocate: Selected Essays, 1941–1988, a fitting companion to the earlier essays of the Antipodean Manifesto: Essays in Art and History and particularly significant contribution to our understanding of the development of art criticism in Australian in the postwar years.

In a talk delivered on ABC radio in 1963, Bernard Smith wrote that the critic should not be impartial, arguing that ‘it is the point of view which always makes [the critic], when the chips are down, advocate rather than judge’. Reminiscent of Baudelaire’s famous statement that criticism should be partial, passionate and political, The Critic As Advocate as a whole exemplifies this maxim.

The explicitly party-political nature of Smith’s critical engagement, which saw his strongly supporting Socialist Realism in the Soviet Union in 1941 and involved in a ranging attack on what he saw as the fascist mentality existing in Australian art in the early 1940s, was to be replaced by a more circumspect form of writing in the late 1940s. And yet his early commitment to social realism (as distinct from Socialist Realism), which courses through all of the early essays and inflects more of his mature writing, provided him with the theoretical and technical means to develop a lucid and impassioned critical style. Writing on the 1943 Contemporary Art Exhibition in Sydney, he stresses that purely abstract and constructivist art was definitely losing its adherents and argues that ‘abstract art will not have a future in Australia; its rigid formalism has little place for the infusion of national qualities’. Far from being modified, this basic position would be reasserted not only in his writings associated with the Antipodean Manifesto in 1959 but also in much of his writing of the 1960s […]

The Critic As Advocate and the republished European Vision represent Bernard Smith in the best of lights: as an outstanding art historian and art critic of great perspicacity and commitment.

Comments powered by CComment