- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Custom Article Title: Move over, Polonius!

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Move over, Polonius!

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Laura Riding, sometime poet and citrus-grower has risen from the grave to deliver this series of attacks on poetry and its untruthfulness. She comes back to us now in a posthumous gathering of essays and shorter notes, The Failure of Poetry: The Promise of Language. It will certainly get people’s backs up.

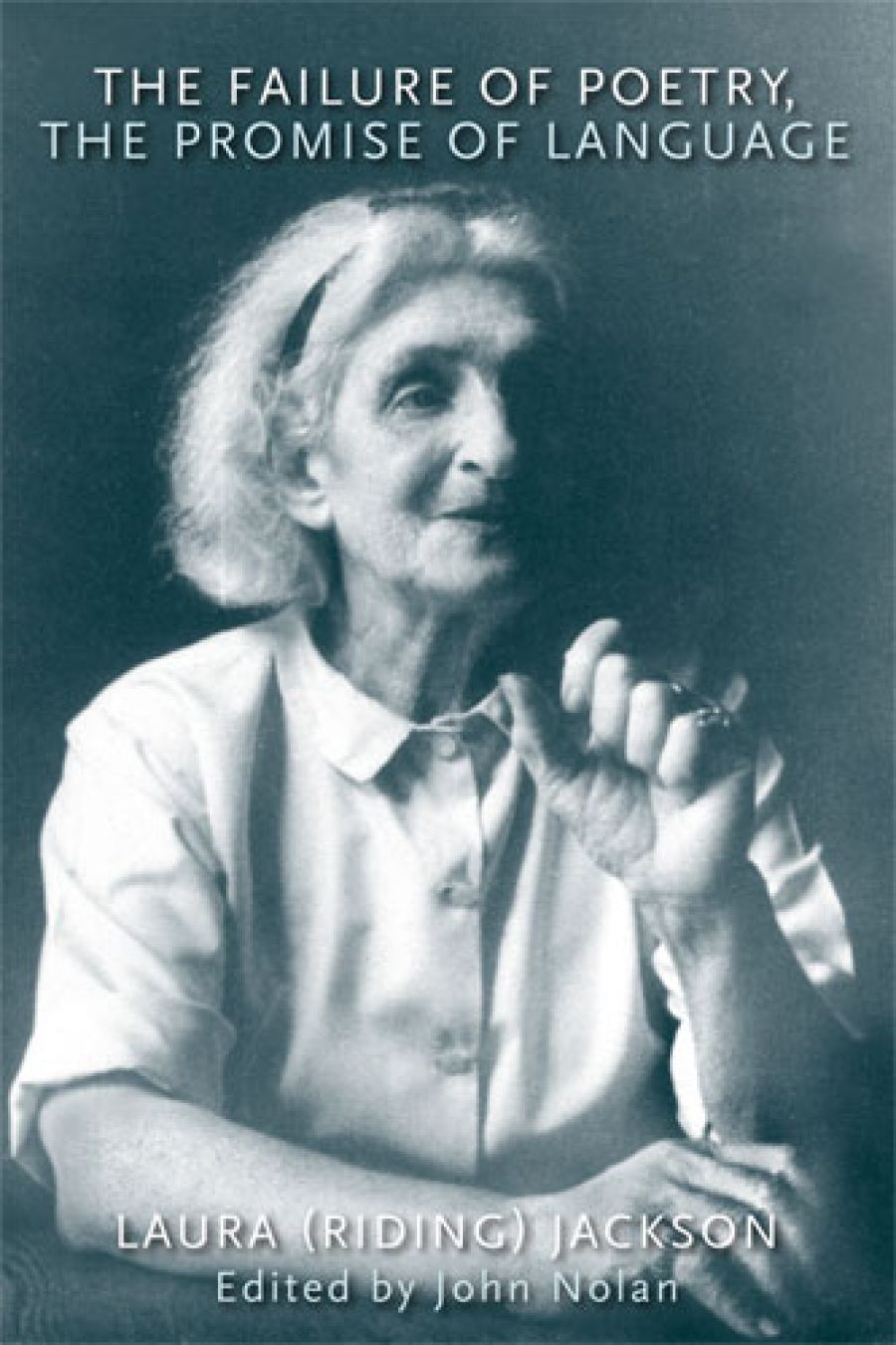

- Book 1 Title: The Failure of Poetry, The Promise of Language

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Michigan Press, US$28.95 pb, 260 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

From the first phrase of Riding’s, or her editor’s, title, one might expect the book to focus on the rise of more popular art forms, on the economic conditions of publishing, or on the structure of modern education. It could well have been an exercise in cultural studies, following through the reasons why books of poetry have all but disappeared from bookshop shelves. This would have been more valuable, in my judgement, given that rather too much of her text, as edited, consists of repeated assertions of an abstract character: in favour of truth, and against Art.

This is a writer who first came to my and many readers’ attention with some slender, gnomic poems in Michael Roberts’s canonical Faber Book of Modern Verse (1935). In those days she was Laura Riding, and her poems sat down there beside exciting work by moderns arrayed from Hopkins to Gascoyne, including a particularly fine clutch of William Empson’s densely worked lyrics.

A little later, I was to find that she was the partner of Robert Graves, having crossed the Atlantic from America after her first marriage and begun babysitting for the Graves family. She certainly went on from that. Although a strong-willed young woman, she hadn’t had much influence on Graves’s poems, bar one or two, traditional as their modes usually were. Her own poetry, however committed to some higher truth, showed the influence of the Tudor poet John Skelton, quirky master of the non-iambic short line. Skelton was also oddball and funny; but it is hard to imagine a writer so strongly, profoundly lacking even the ghost of humour, as Laura (Riding) Jackson. Otherwise, how could she ever have hatched the addled egg of this sentence?

The male-female liberalising of the ideology of the new poetry is a conspiracy of willful confusion imposed on the production-site of twentieth-century poetry by all who place their poet-identity under the protection of this ideology.

Move over, Polonius! Possessive phrases have taken over, like cloth-eared commissars. Seriously, though, how does a writer find her way to the admired language of truth if she can no longer write with conviction? This decline is particularly sad, because the former poet had set herself a task of high moral ambition. Wishing to sweep aside the gaudy triviality and deplorable subjectivity of modern poetry (as far back as Burns and Clare, at least), she sought a way to establish more satisfactory uses of language. Her seriousness is genuine, without a doubt.

It is a solemnity from quite another world than Henry James’s famous dictum to the writer, ‘Don’t state. Render.’ But (Riding) Jackson’s claim for a natural language, for strict truth-speaking, has no place for rendering; it does not seek mimesis at all.

Then, what on earth would she have made of Keats’s plea that poetry ‘cannot be matured by law and precept, but by sensation and watchfulness in itself. That which is creative must create itself’? Or of T.S. Eliot’s canny remark on the best of Byron: ‘Digression, indeed, is one of the valuable arts of the story-teller’? But then, our stern chider had a particularly low opinion of Eliot, much lower even than of Pound.

The book is consistent in its attitudes: including its promise of the promise of language. But the nature of this desirable truth-discourse remains unclear: or else, something close to a nerdish ideal. Indeed, I have striven to and fro through this book to grasp a clearer sense of her truth-speak, but it keeps slipping away like a wet watermelon seed – to use the kind of simile that she mistrusted so utterly. As I have suggested, she seems to have had little sense of history, which doesn’t hurt much since poetry was on the wrong foot from the beginning.

Nor do I find much philosophical acuity here. Her scepticism has a little in common with early Russell; Wittgenstein is mentioned in a footnote, but at third or fourth hand. Even the American pragmatists fail to get a look in. Paradoxically, it seems that the author launched a forty-year assault on the pretensions of poets without having read anything but poetry: and, for the most part, modern poetry, plus whatever she and her later husband, Schuyler Jackson, explored in their lexicographical work.

There is something heroically sad about all this, and one could easily be tempted to read the whole project by means of an argumentum ad feminam, seeing Laura’s later career as a process of compensation for personal slights and sorrows. But for me to argue thus would be even worse than my being a poet.

Comments powered by CComment