- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Custom Article Title: No ideas but in things

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: No ideas but in things

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

We begin by peering through a window, watching a carpenter hard at work, engaged, precise, among tools and apprentices. Suddenly, we are glimpsing a lab technician working on rabbit cadavers; next, we are in a concert hall, our eyes keenly directed toward the conductor. We encounter these three craftsmen many times throughout Richard Sennett’s enthralling inquiry into the nature of craftsmanship. Their ranks are joined by ancient weavers, medieval goldsmiths, Linux programmers, brick-builders, luthiers, architects, glassblowers and those who constructed the first atomic bomb.

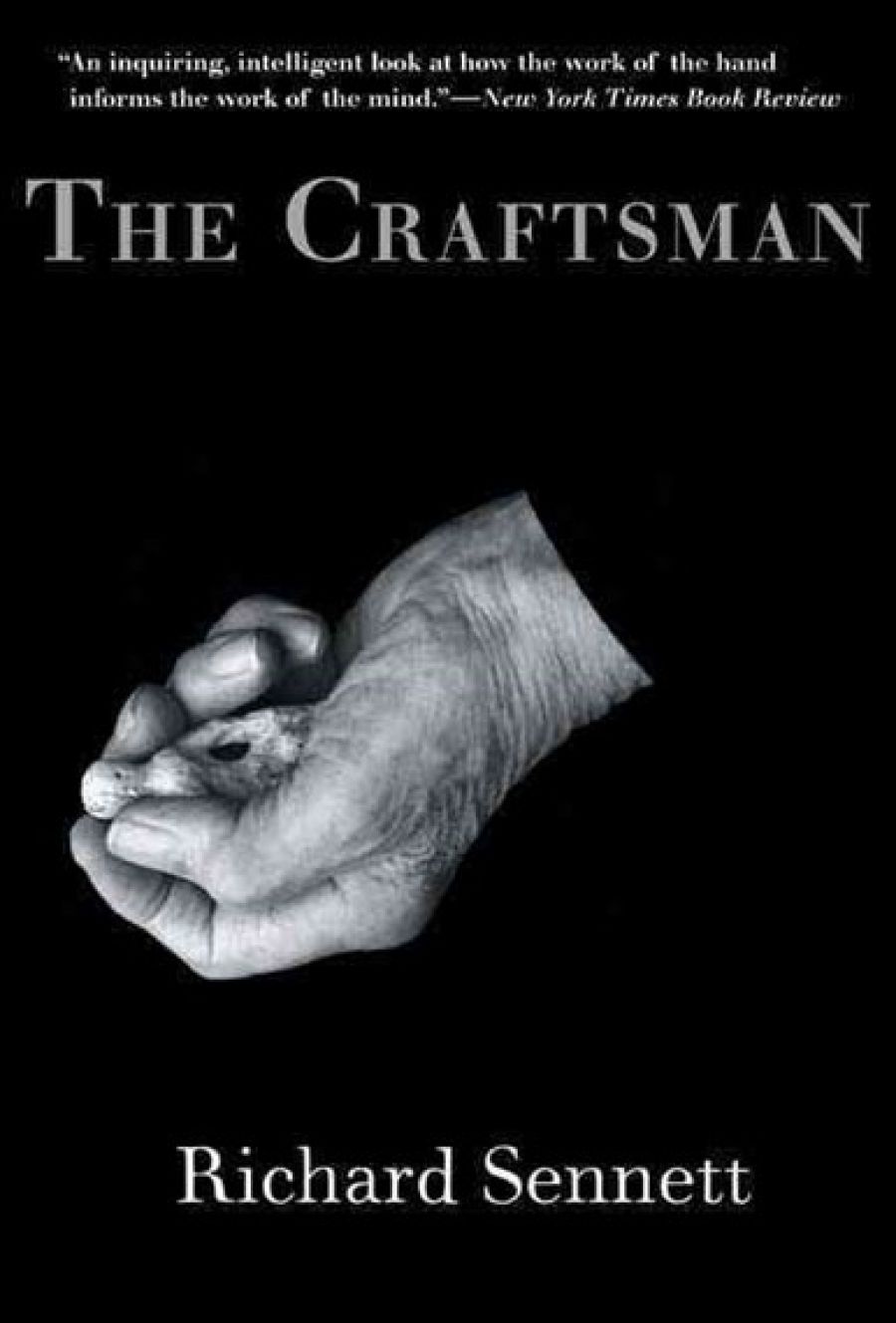

- Book 1 Title: The Craftsman

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen Lane, $59.95 hb, 376 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Here, Sennett sets about rescuing the eponymous craftsman from his reputation as Animal laborens, the term his teacher, Hannah Arendt, used to describe a person who performs purely manual labour, as opposed to ever-thinking Homo faber. Sennett is quick to dissuade us of this myth, that manual labourers have no need to think complexly and potentially possess no great capacity to do so. He encourages the reader to consider the importance of imagination, response to error, and methods of instruction that true engagement with a craft entails. For Sennett, craftsmanship demands an awareness of the relationships between mind and body, head and hand.

In our world of ‘material culture’, where we constantly use objects without having any idea about their construction, functionality and repair, these are radical thoughts. The development of an awareness of the processes underlying particular crafts has become increasingly important since the eighteenth century brought the Industrial Revolution, the machine and the abundances that ensued. Sennett argues that we must recognise the importance of objects and our relations to them: via touch, smell, thought, for example. We must also realise the many ways in which we can interact with them, alter them but in this process be altered ourselves: a craftsman, whether he or she be a cook, a ship-builder or a doctor is constantly evolving through interactions with their environments. For example, in the late 1400s much sharper knives became available because iron was now mixed with a silica and knives could thus be sharpened on blocks of stone rather than on leather straps. This led to the production of the modern scalpel: ‘In the first generations of the scalpel’s use, surgeons had to deduce by trial and error how they could best use it.’ This is a paradigm of a craftsman needing to evolve in relation to an object, to learn from mistakes and to endure salutary failures.

One of Sennett’s commanding qualities is his ability to build his argument through case studies. Their cumulative effect allows Sennett to substantiate his abstract claims concerning craft in general by grounding them in reality. Thus, when stating that difficulties in craft need to be visualised in order to be solved, he is able to invoke the ‘mental map a musician makes for a chord stretch’, the ‘sensate border’ the fingertip becomes when a cook evaluates the ‘fleshy firmness of a slaughtered chicken’, and the visualisation a goldsmith must undertake in assaying gold, the fingertips probing the surface while the mind works with it to tell the customer whether or not the nugget is valuable.

Sennett’s history and discussion of craftsmanship throughout the ages is by no means linear. Nor should it be. If it were, we would not be able to see connections which become evident when the content is organised thematically, such as Sennett’s links between ancient potters and Linux programmers and the mimicry of the right-angled ‘cloth join of warp and woof’ in the ‘mortise-and-tenon joint’ in shipbuilding, which itself metamorphosed into urban design.

The Craftsman is divided into three parts: Craftsmen, Craft, and Craftsmanship. The first looks at the types of problems a craftsman encounters, the idea of the workshop as a social space, the advent of machines and their effect on craftsmen in general, and the relationship between craftsmen and the objects they encounter. The second concerns itself with the hand and its relation to both the mind and external objects, how to instruct others in craft, the role and uses of imagination in craft, and the concepts of resistance and ambiguity. The third demonstrates the controversial claim that talent is not as important as motivation in becoming a good craftsman.

Part Two contains an extended discussion of the concept of resistance as seen in craft. Sennett tells us of a time when the English realised that London was expanding so rapidly that the only way to transport water and remove waste was by building tunnels underground. London ground was an unstable muddy mass, but in 1793 the Brunels constructed a mobile metal house, one wall of which had small slits in it, which could be pushed underground through the mud while people built a brick-lined tunnel behind it. This underground house was able to be advanced only ten inches a day out of four hundred yards because the Brunels were working against the mud, not with it. It took fifteen years, being completed in 1841. Then in 1869 a tunnel was built under the Thames in just over eleven months, using a snub-nosed structure, which worked with the resistance. The idea of resistance is of fundamental importance in craft. It is exactly that which craftsman need to work with, not against: ‘resistance obliges us to revise.’

Sennett identifies two types of resistance, describing them in terms of cell walls and cell membranes, the former allowing nothing to pass through, the latter allowing both fluid and solid exchange to a certain degree. It is these latter borders that create a necessary ambiguity for the craftsman, manifesting themselves in Van Eyck’s Amsterdam playgrounds, where the edges between the sandpit and the grass are blurred, where the playground stops at a traffic light and resumes on the other side of the street, also manifesting themselves in Avignon’s walls becoming hubs for the sale of black-market goods. It is through resistance and difficulty that we learn, through repairing broken tools that we gain knowledge; to become a master craftsman, both the apprentice and the journeyman need to suspend their ‘desire for closure’.

It is the continual discourse engaging both mind and body, touch and thought, that is important. Some may wonder about the designation of computer programming as a craft vis-à-vis soldering, since a programmer creates software which does not have a physical presence. This is exactly the point. Craft does not occur only in the physical realm. As we approach the final pages, we cannot help but ask ourselves: is Sennett, the writer, a craftsman?

Sennett has dealt elegantly and expertly with many differing and divergent aspects of craftsmanship and, in his conclusion, tackles something he dubs the Philosophical Workshop. The great paradox of The Craftsman is how we can even discuss, let alone write about, issues of such a corporeal nature without necessarily experiencing them first-hand. Sennett himself is firmly grounded in the philosophical school of Pragmatism, which aims to make ‘philosophical sense of concrete experience’. This is exactly what he does, and we are indebted to him for it. Invoking Hephaestus, the club-footed master god of craftsmen, a recurring theme juxtaposed against the terrors of knowledge unleashed by Pandora, Sennett seems to be urging us to go and build a table, learn to solder, glassblow or weave, pick up a piece of golden metal and assay it, using touch as a tool along with our minds, consider objects along with their implications for us. He urges us to believe the words of William Carlos Williams, that there should be ‘no ideas but in things’.

Comments powered by CComment