- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Military History

- Custom Article Title: All in!

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: All in!

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Not many Australian historians have managed to publish major books, based on years of scholarly research, which have evoked both immediate and enduring acclaim. It therefore says something both about intrinsic value and about the tastes of the book-buying public when such a book goes into a second or even a third edition, ten or more years after its first appearance. The weeks preceding Anzac Day are always a popular time for the publication of books on military history, but this year has been especially notable for witnessing a number of reissues, alongside a flood of new titles. The two under review here are the third edition of Jeffrey Grey’s A Military History of Australia, and the second edition of David Horner’s and Jean Bou’s history of the Royal Australian Regiment, Duty First. Others include the third edition of Ken Inglis’s highly acclaimed study of war memorials, Sacred Places, and new issues of Ross McMullin’s biography of Major General ‘Pompey’ Elliott and Gavan Daws’s Prisoners of the Japanese.

- Book 1 Title: A Military History of Australia

- Book 1 Subtitle: Third Edition

- Book 1 Biblio: CUP, $120 hb, 334 pp, $39.95 pb

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

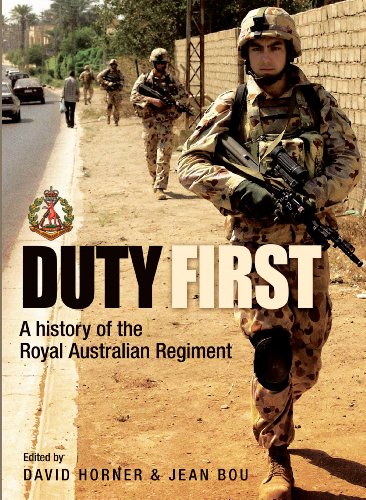

- Book 2 Title: Duty First

- Book 2 Subtitle: A history of the Royal Australian Regiment, Second Edition

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $49.95 hb, 526 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

A Military History of Australia is a magisterial overview. A remarkable amount of detailed information is enlivened by robust coverage of many of the longstanding debates. Grey does not refrain from expressing vigorous judgements. Not everyone will agree with all of them, but most will concede that they are based on extraordinarily thorough knowledge of the relevant sources.

Grey particularly enjoys puncturing common myths: a recurring phrase is ‘contrary to popular opinion’. At this time, with a new Labor government facing major challenges in defence, it is worth noting that his treatment of the defence-related myths associated with both Labor and Coalition governments is commendably even-handed. Take, for example, his treatment of Robert Menzies and John Curtin as prime ministers during World War II. The post-1945 ‘Curtin legend’, against which Menzies railed at the time and which prevailed in much historical writing thereafter, held that Menzies was subservient to Winston Churchill and the British Establishment, and that he did not inspire wholehearted commitment to the war effort by the Australian people, whereas Curtin was an outstanding leader whose oratory, and willingness to stand up to Churchill, made him ‘the saviour of Australia’.

Grey, by contrast, writes that Menzies ‘did better than he has been given credit for’. Menzies was seriously misled by the British over the Greek campaign, but in general he stood up to Churchill more robustly than Curtin did to General Douglas MacArthur. Menzies’ use of the slogan ‘business as usual’ was unfortunate, but it was his government, not Curtin’s, that coined the phrase ‘All in’. As Grey notes, the relationship between the Australian and American high commands in the Curtin–MacArthur era was complex, but the benefits flowed largely one way. One outcome of Curtin’s surrender of sovereignty to MacArthur was the prolongation of the debilitating feud between the two most senior officers in the Royal Australian Air Force, which greatly undermined the effectiveness of that service.

But this is no anti-Labor tract. Grey’s coverage of the Labor government of 1972–75, with Gough Whitlam as prime minister and Lance Barnard as minister for defence (for all but a few months), concludes that the period ‘should refute the popular notion that Labor governments are somehow “soft” on defence issues’. The 1970s saw major reforms in defence, both in organisation and (less prominent in Grey’s account) in strategic policy. At a time when few saw any military threats to Australia, Whitlam was much more interested in foreign policy than in defence. Barnard (whose father had been minister for repatriation, as Veterans’ Affairs was then known, in the Chifley government) knew more about servicemen’s benefits and welfare than strategic or operational issues. As Grey rightly records, the dominant figure in the major defence reforms of the 1970s was the Defence Department secretary, Sir Arthur Tange, but Whitlam and Barnard commissioned ‘the Tange reforms’ and did not shrink from implementing them.

Grey covers the significant policy, administrative and operational developments under the Labor governments of the 1980s in some detail, noting the leadership of Kim Beazley as defence minister. While he notes the benefits that Australia has accrued from staying allied to the United States after New Zealand effectively withdrew from ANZUS in the mid-1980s, he could have given greater credit to Bob Hawke and his ministers for preserving the alliance when it was under real threat.

There is still some myth-busting to be done in Labor ranks. We know that Kevin Rudd gave President George W. Bush a biography of John Curtin during the APEC meeting last September, as a way of signalling that Labor was not hostile to the Australian–American alliance. But for a Labor prime minister who wants to maintain and modernise that alliance, without appearing spinelessly subservient, the real heroes should be Hawke and Beazley rather than Curtin.

Sometimes one wonders whether the myths that Grey punctures still hold much air. How many Australians still believe, for example, that Singapore fell in 1942 partly because the guns at the great naval base could only be fired out to sea, and were therefore useless against the Japanese army’s advance down the Malayan peninsula? Grey quite rightly says that the guns could in fact traverse through 360 degrees, but their flat trajectory and high-explosive shells were more suitable for naval than for land targets. But the tale of the guns of Singapore was probably a myth of the last century, not this one.

On the other hand, many other myths have long endured and deserve their treatment here. The idea that Australian servicemen always held senior British officers in contempt, especially during the two world wars, is ably qualified and nuanced. Grey manages, within a tightly written overview, to convey many of the complexities and subtleties of the Anglo-Australian military relationship, pointing to strengths and weaknesses on both sides.

Unfortunately, he does not touch upon the controversies surrounding the loss of HMAS Sydney in 1941, of which we have recently been reminded. The topic offers great scope for Grey’s puncturing of wild theories. (The index regrettably refers to the various ships successively named HMAS Sydney as if they were but one.)

His touch is not quite so certain on more recent events. In dealing with the controversies that embroiled the Defence Force during the 2001 election, Grey seems to have conflated SIEV X (the vessel that sank near Indonesia with great loss of life) with SIEV 4 (the vessel at the centre of the notorious ‘children overboard’ allegations).

Grey’s bibliography is not a mere list but a commentary on the principal books and articles on which he has based each chapter. Several of those works are by the prolific David Horner, whose contribution to Australian military history, as author, co-author, editor, co-editor or series editor, is unmatched in its scope, detail and precision. Duty First is a revised edition of his history of the Royal Australian Regiment, the principal combat element of the standing professional army established in 1948.

Co-edited with Jean Bou, who is one of the team working with Horner on the fifth series of Australian official war histories, Duty First is what might be called a Gettysburg history – a history of the regiment, by the regiment, for the regiment. Unlike Grey’s history, it is not aimed at the general reader, but its readership should not be confined to past, present or prospective members of the RAR. To read this account of its service, from Japan and Korea in the late 1940s to East Timor, Iraq and Afghanistan today, is to gain some understanding of the meaning, for the infantry soldier, of the decisions taken by prime ministers, defence ministers, and their most senior military and civilian advisers. It demonstrates the importance of the shift in the late 1940s from the predominantly civilian army of both two world wars to today’s professional army; and it gives some depth and substance to the pious phrases about service and sacrifice to be heard every Anzac Day.

Comments powered by CComment