- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Children's and Young Adult Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: So very much different

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

On the morning of 12 August 1864, Hannah Duff sent her three children – Isaac, aged nine, Jane, seven, and Frank, almost four – to gather broom from bushes growing a short distance from their one-room slab hut in the West Wimmera district in Victoria. They walked into the mallee scrub, and that was the last their mother saw of them for over a week. By some miracle, the children survived and were eventually found on the evening of August 20 by a search party which included three Aboriginal trackers. The children had walked nearly one hundred kilometres in those nine days, including twenty kilometres on the first day and six on the last. News of the rescue swept the state and the intense press interest in the siblings and their extraordinary adventure led to the establishment of an educational fund for them, but in particular to reward Jane for her nurturing of her brothers. The Aboriginal trackers were also financially rewarded. When Jane died in 1932, the words ‘bush heroine’ were inscribed on her gravestone.

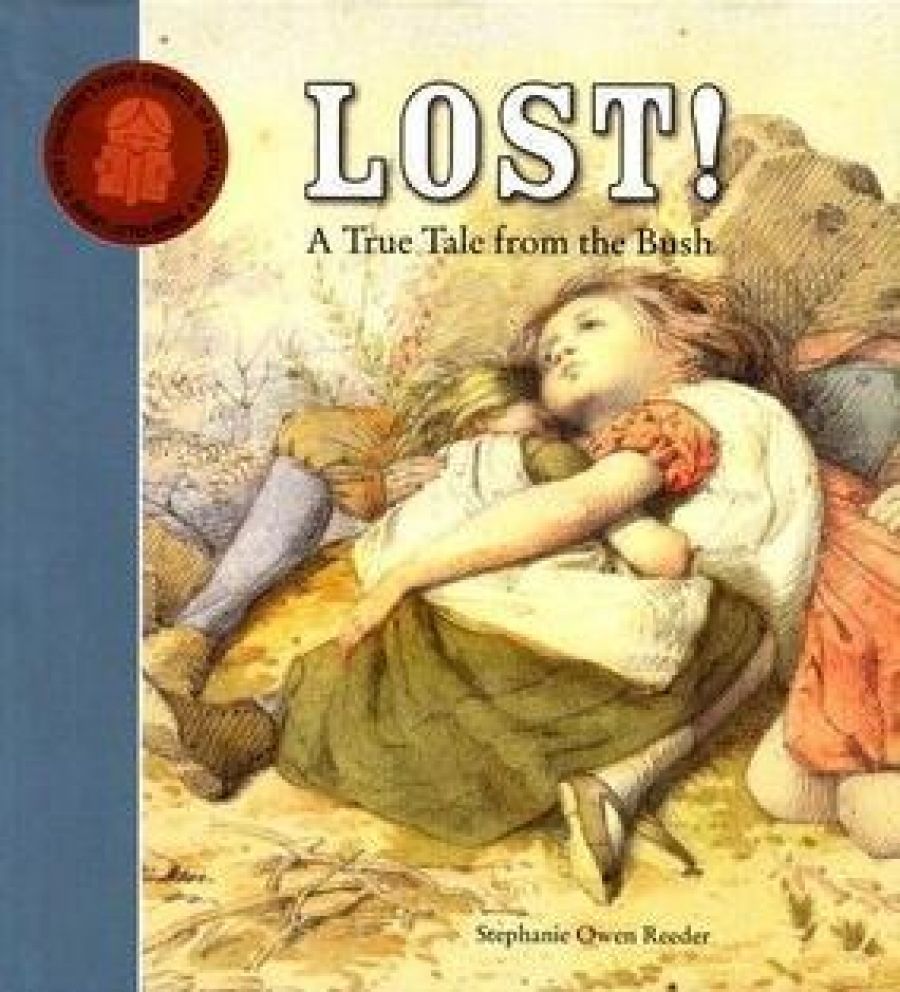

- Book 1 Title: Lost!

- Book 1 Subtitle: A True Tale From The Bush

- Book 1 Biblio: National Library of Australia, $29.95 hb, 110 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Title: 60 Classic Australian Poems

- Book 2 Biblio: Random House Australia, $19.95 hb, 160 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

As Stephanie Owen Reeder notes in the introduction to her own retelling, over the years the tale of the three ‘babes in the bush’ was to inspire authors, artists and filmmakers, including William Strutt (1825–1915), an English artist who lived for some years in Australia. Cooey, his fictionalised account, was published in 1876, and in turn inspired Owen Reeder, who has included his watercolour illustrations in her book. These, together with Strutt’s manuscript, are held in the National Library of Australia, as are the originals of the more than eighty reproductions from the Pictures Collection used throughout Lost! A True Tale from the Bush to embellish not only the story of the Duff children but also the factual information about early settler life given at the end of each chapter.

While it may be helpful to remind young readers that there were no cars, planes, televisions or electronic games in the 1860s and that children had to entertain themselves with the likes of ball games, hopscotch and tree climbing, such intrusions do not help sustain a mood or maintain narrative suspense. At the end of the fifth day, when rain has washed away all traces of her children’s tracks, Hannah Duff, alone and waiting in the bark hut, gazes at the soggy bush through her tears: ‘Hope had abandoned her.’ Turn the page and you are confronted with a two-page illustrated discussion of children’s toys of the period. Young readers who have grown up with commercial television may not find this disruptive and, of course, these pages and the others like them may be left for later, but they may partly account for my finding Owen Reeder’s narrative curiously uninvolving. They do, however, make full use of the National Library’s pictorial resources, which, in many cases, have inspired the author’s own illustrations. Keep a sharp eye out: on the needlework sampler supposedly made by Jane Duff you can just make out the name S.M.S.M. Franklin, embroidered by the eleven-year-old Miles Franklin in 1890.

Owen Reeder uses an omniscient viewpoint but perhaps her experience as an editor and history teacher has encouraged her to stay on the surface of the narrative, which is heavily informed by eyewitness and contemporary newspaper accounts. She invents dialogue but generally refrains from entering the hearts and minds of her characters; and she keeps a tight rein on emotions in the potentially dramatic scenes (‘Tears flowed as she gazed ...’; ‘Many a tear was shed ...’). In the final pages and the climax of the story, the tension is undermined by her habit of starting sentences with ‘and’: ‘And so the search continued … And so he dropped the reins … And it was there that … And to his indescribable joy … And Jane’s dress was … And as for poor ... And so the searchers ...’

If I could have wished for a little more excitement in the telling of the tale, it must be said that the book is a gorgeous production. With its high-gloss paper, gold-embossed hardcover and jacket illustration of William Strutt’s charmingly sentimental The Little Wanderers, it will be a highly promotable volume in gallery bookshops, and a useful resource for primary school readers who have been overlooked amid the flood of ‘lost children’ narratives that over the decades have figured heavily in adult literature.

It is back to the bush again with 60 Classic Australian Poems, edited by Christopher Cheng and illustrated with black-and-white sketches by Gregory Rogers, the team responsible for 30 Amazing Australian Animals (2007). The series has obviously been a success, due in no small measure to Rogers’s amusing and always evocative illustrations – and not having to pay copyright on poems must help. There is nobody represented in this volume who was born later than 1878 (Louis Esson and P.J. Hartigan), and only one (Mary Hannay Foott) is female. The collection is dominated by the works of ‘Banjo’ Paterson (fifteen poems), C.J. Dennis (fourteen) and Henry Lawson (seven), and almost eighty per cent involve the bush or native animals – which makes me wonder what the editor would have done without Dennis’s A Book For Kids (1921), the source of most of the poems that don’t.

In his introduction, Cheng gives as his criterion for selection that ‘each poem or ballad tells a complete story of a time in Australia’s recent history’ when life was ‘so very much different’ from the ‘more comfortable and chaotic life that we live now’. Not many of the poems convinced me that this is actually so, and the ones that in some way deal with weather – John Shaw Neilson’s ‘Waiting for the Rain’, Paterson’s ‘Song of the Artesian Waters’, Hartigan’s ‘Said Hanrahan’ – only prove that the more things change the more they stay the same. The book concludes with Biographies, Book References, Index of First Lines, Index of Poets and full references for all poems. Like Lost!, it will be snapped up by gallery shops and school libraries.

Comments powered by CComment