- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Maestra

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Piano lessons have been a source of joy or frustration for generations of Australians. By the early twentieth century, there was a piano for every three or four Australians. Skill at the pianoforte was an accomplishment that bourgeois parents desired for their children, especially daughters.

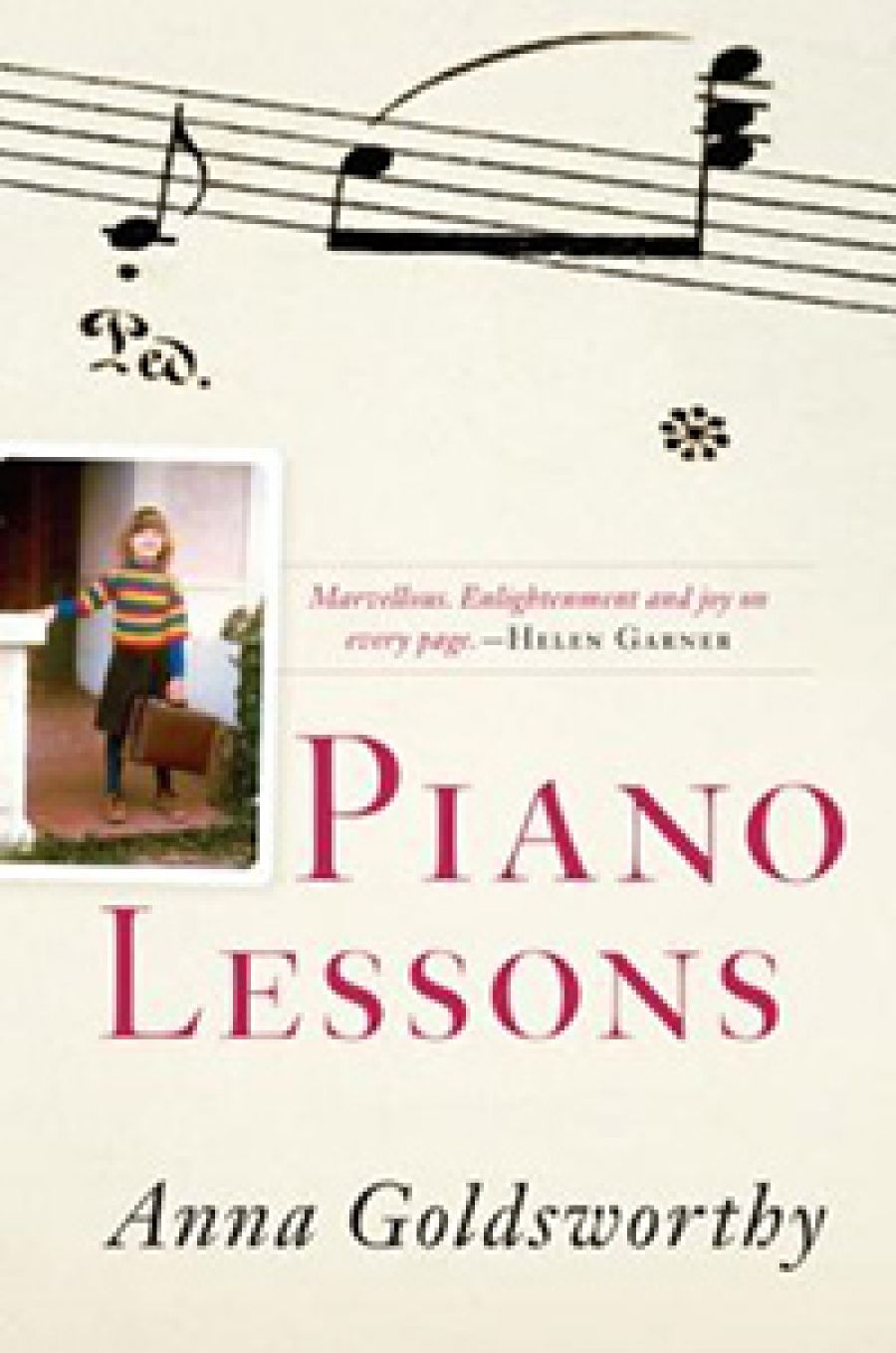

- Book 1 Title: Piano Lessons

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $27.95 pb, 224 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

After the first few lessons, Anna’s parents, both doctors, swapped shifts so that her father, Peter Goldsworthy, author and keen pianist, could drive her to the lessons. For the next eight years, he attended the often long sessions, ‘listening, day-dreaming and taking notes’. Some teachers might not have welcomed such intense parental involvement, but in this instance it was a congenial arrangement. It also resulted in the publication of his novel Maestro (1989). Identical dialogue appears in both books, and incidents relate back and forth between Adelaide and Darwin, Anna and Paul Grabbe, the young pianist in Maestro; Mrs Sivan and her fictional exemplar, Eduard Keller. Peter Goldsworthy, far from being a detached witness, had transcribed the conversations of the lessons.

Both teachers – real and imagined – are on the ‘Liszt List’: descendants of an extraordinary musical ancestry. Beethoven taught Czerny who taught Liszt who taught Leschetizky who taught Annette Essipoff who taught Mrs Sivan’s professor at the Leningrad Conservatorium. Mrs Sivan wasn’t the only ‘descendant’ in Australia, either. Recently, ABC Radio National’s PoeticA featured Ross Bolleter, who was taught in Perth by Alice Carrard, a Bartók branch of this intriguing lineage.

When Anna, aged fifteen, already a precocious editor of her father’s manuscripts, discovered his Sivanian appropriations, she was shocked. But with each revision the book became more imaginative, more fictional. Ultimately, Mrs Sivan was pleased by her inclusion in the book’s acknowledgments. Last year, father and daughter collaborated on a theatrical adaptation of Maestro.

In Piano Lessons, Anna’s recall of conversations is impressive. Are all Mrs Sivan’s words in her head, along with scores of scores? Perhaps Anna consulted her father’s notes. Whether she did or not is of no consequence, so effortlessly do they blend into the narrative. The reader begins to understand the harmony (or ‘garmony’) of this phenomenal teacher. A ‘pearly legato’ pervades the book. The unintended humour of her pronouncements is gloriously captured: ‘Beethoven so intensive. He eat you’; ‘Pianissimo can mean lullaby or it can mean enormous tragedy. And of course pianissimo for elephant is still fortissimo for rabbit.’

Anna, with few hiccups, glides through school, winning scholarships and eisteddfods. Her goals are huge, but she also records some amusing put-downs. At house athletics trials, someone asks her if she is ‘the brain’ and Anna admits she is. ‘Well it’s a good thing you can do maths, because you’re fucking hopeless at hurdles.’

Even prodigies have crises of confidence. Anna suffers the usual embarrassments of adolescence. She develops a highly complicated set of superstitions, both Russian and home-grown. Any child who arranges torn gum leaves into the beginning of the Fibonacci sequence, while noticing her companion scrunching hers into a ball, has to be complex. Despite her parents’ devotion, Anna feels isolated and worries about her dependence on Mrs Sivan. Practice and achievements become her form of self-knowledge, no longer a pleasure but a source of relief at not failing. Her secondary schooling ends, and with the disintegration of her lucky bra she discovers, as a ‘recovering magical thinker’ verging on the ‘obsessive-compulsive’, complete with ‘aural hallucinations’, that everything has worked out in the end. Her talent and dedication lead to local triumphs in Adelaide and to further studies in the United States and Melbourne.

Descriptions of accidents and concert glitches will engross the reader, for Anna’s vertigo and sinking stomach transcend the pages. Anyone who has ever performed or sat a music examination will feel a wave of empathy. All the voices in the book come to life, but the author has been careful to protect her own and other people’s privacy. Everyone is mentioned fondly, but, such is the author’s restraint and maturity, some characters are enlarged and others not.

Towards the end of this warm, absorbing memoir, Mrs Sivan becomes ill and the situation is described movingly. Her small, flying, pink, starfish hands lie heavy and still on the hospital sheet; the loved face is immobile. But recovery is possible. Then, as if magically, there is the discovery of the start of a new life.

Comments powered by CComment