- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Parry and front

- Article Subtitle: Les Murray revisits the Black Dog

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Lawrence warned us not to trust the teller, but to trust the tale. Nevertheless, all writers are apt to suffer the fate of being confused or conflated with their works. Maybe it is part of what Goethe entitled Dichtung und Wahrheit. If truth is going to be let into poetry, many readers want to know the facts about the poet: both the jubilant facts and the disconcerting ones. This is not merely irritating nosey-parkerhood. The shimmering glamour of writers is inevitably part of their stock-in-trade. A Byron, a Plath, a Rimbaud, Dickinson or Dylan Thomas has become inseparable from that poet’s reported life, dazzle, sex and dirt. An early death helps no end. It is an example of fatedness which Al Alvarez explored years ago in The Savage God (1971), a title he derived from Yeats talking about Charles Conder and his decadent allies of the 1890s.

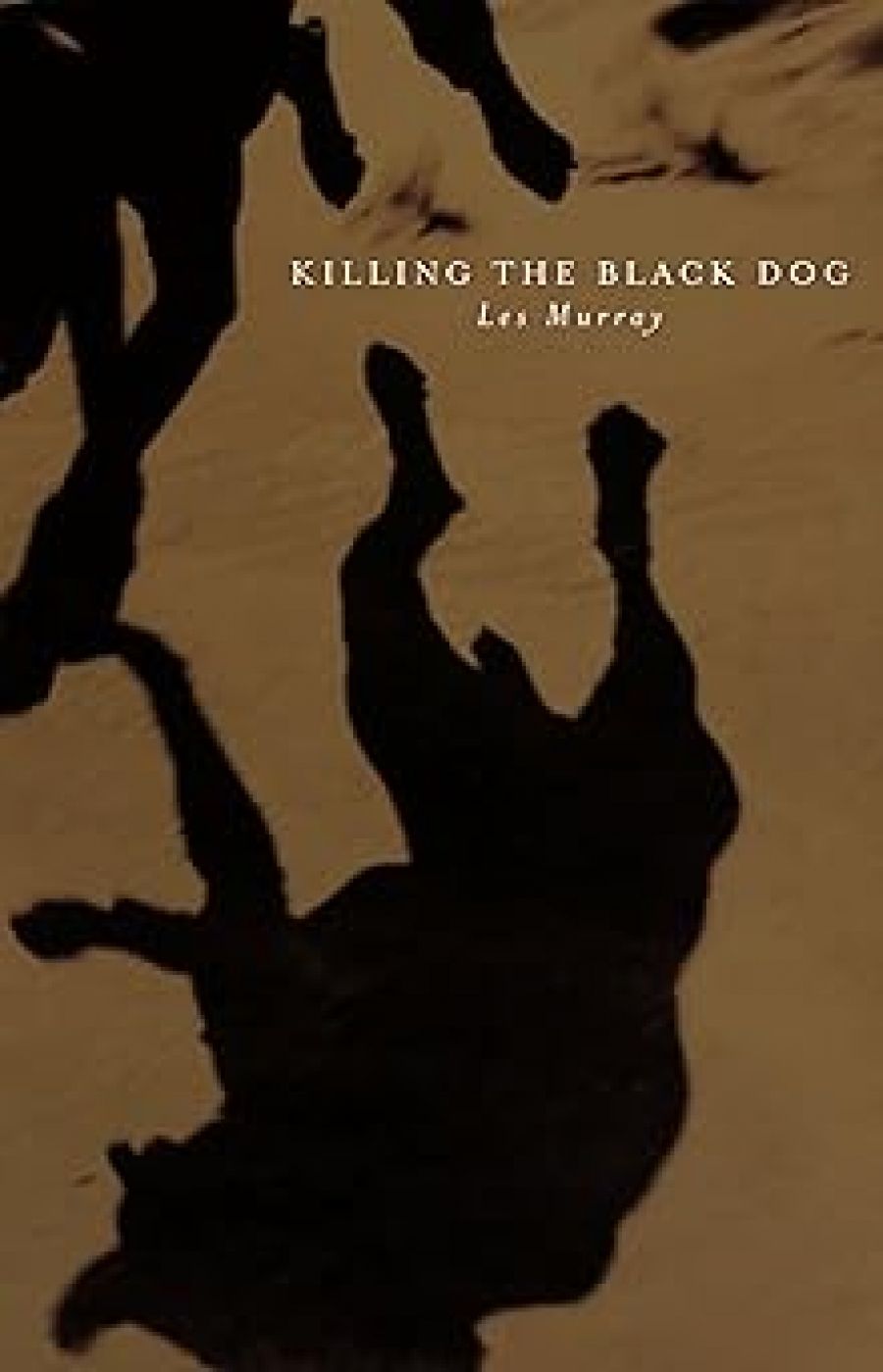

- Book 1 Title: Killing the Black Dog

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $24.95 pb, 88 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Among living poets of this country, Les Murray is surely the one whose poetry is most desperately entangled with his views and attitudes. Particularly within Australia, there are many critics who find his views so reactionary or so in-your-face that it darkens their response to the poetry. What is more, Murray appears to rejoice in this – some of the time. Like Yeats, he has a creative, enabling mask to play with; like him, Murray would like to associate himself with whatever our equivalent of the peasantry might be, in touch with the earth and rural verities, rather than with urban professionals and their sometimes trendy politics.

Black Inc. has just published an expanded edition of Murray’s Killing the Black Dog. What is, or was, the Black Dog? Many readers will already know the relevant story, but for those who don’t it includes the early death of the poet’s mother, false myths about her death, personal obesity, fear of sex, unhappy schooldays, ‘the harsh floggings I got for being a bad boy’, loneliness, bookishness and comparative poverty. His world view grew from this pain and alienation, even from successive breakdowns. ‘I’d been cursed, and refused to notice or believe it’, as one poem here puts it, and in another, ‘Between classes, kids did erocide: destruction of sexual morale’.

Part of the poet can remember far back a scruffy pastoral arcadia where all went well, or could do, in the right circumstances: something that would never be trendy. One of his ‘Sound Bites’ puts his present sociology in a single line, ‘Poor cultures can afford poetry, wealthy cultures can’t’. By implication, moreover, urban cultures can’t. This is also a paradox, given that Murray has been so frequent an overseas traveller, as well as being proudly rustic at Bunyah. Does he contradict himself? Yes, we all do.

Perhaps, like me, he enjoys the tranquillity of air travel, its lofty readerly peace, once you have escaped the concrete airport’s bureaucratic bustle. What a place to read long books, I always think when the plane at last takes off. In Andrew Marvell’s earlier terms, ‘Society is all but rude / To this delicious solitude’. But there has also been a career bonus for Murray, who confesses that ‘outside my own country I’m fine and can once more earn half of our living from overseas readings’.

In a telling sentence, Murray writes, ‘nearly all my quarrels have been with the official culture, of universities, media and government agencies, people who have agendas, or lines to toe’. This is something of a bizarre statement, given Murray’s role as our most wide-ranging and successful poet, perhaps our greatest. And it sits beside such angry verse as this stanza from ‘A Stage in Gentrification’:

Sex, media careers, the Australian republic

And recruited depression are in that bag

With scorn of God, with self-abasement studies

And funding’s addictive smelling-rage.

In 1997 the poet confronted this sense of cultural alienation – if that is not too strong a word for such a successful writer – with a small, confessional book, entitled Killing the Black Dog. This contained tough poems and a long essay. Christine Alexander defined Murray’s brave essay as ‘the first occasion on which he has written so frankly about his persistent depression and its relationship to his writing’. It ended optimistically with Murray’s relief that the Black Dog had left him at last. As the new edition of Killing the Black Dog reveals, he was not so lucky. But I will return to that shortly.

Murray’s contemporary and fellow-Catholic poet Peter Steele has recently written this about the linguistic art they richly share: ‘poets might be said to have “unfamiliars” – that is, any number of beings seen predominantly in their strangeness.’ Nothing could be more appropriate to Murray’s poetic oeuvre. From the beginning, he has captured the strange particularity of things and creatures, of forests, highways, silky oak trees and even a burning truck. This power became most intense in the miniatures of his collection, Translations from the Natural World (1992), in which he acutely sought the inscape (Hopkins’s excellent term) of myriad creatures. But it is also displayed in the density of such big poems of his as ‘Bent Water in the Tasmanian High-lands’ and ‘The Buladelah-Taree Holiday Song Cycle’.

On the poet’s own evidence, we might now see that captured strangeness, that ‘translation’, as related to his pain. He continues to feel his distance from the common diurnal world, from the webs of society. And he is willing now to see the condition as springing from Asperger’s syndrome – whatever that has arisen from, in its turn. A recurrence of his panic attacks even prevented him from flying to Europe in 2005.

The most surely heartbreaking poem here, eschewing his usual verbal richness, is called ‘The Averted’:

The one whose eyes

do not meet yours

is alone at heart

and looks where the dead look

for an ally in his cause.

Yet this lyric is rhetorically calmer than some of Murray’s depressive anger poems, perhaps because it belongs to a new era, there being seven new poems in the collection. It takes on board the knowledge that there wasn’t merely a running war against the fat, the puritanical, the untrendy and the unsexy, but a condition running far deeper than all that pain: if anything can flow much deeper than pain.

There is something courageous about exposing all the discernible sources of your rage, an anger which could be mistaken for chronic righteousness. For, in this book, Murray is frequently revealing his rage as well as his pain, and digging deep for their roots.

After a near-lifetime of panic attacks, along with a liver illness that carried him close to death, he is up and running at seventy. The boy who found to his cost that outside your family ‘there’s only parry and front’ has found a degree of ease, despite his admitted strain of Asperger’s syndrome. With the aid of an antidepressant drug, he has ‘become less afraid of Australian women and less self-absorbed. At seventy I’m more at ease with what Homer Simpson called his womanly needs.’ The comparison with Homer Simpson is democratically attractive. Killing the Black Dog is a harsh and uncomfortable book, and it contains twenty-four of his least attractive poems, many of them brave. It also holds this stanza:

Remember how I used

to carry ice in from the road

for the ice chest, half running,

the white rectangle clamped in bare hands

the only utter cold

in all those summer paddocks.

An evocative, physical reaching-back which leads me to my recurrent question: whether Thinking belongs to the world of comedy, Remembering to that of tragedy.

Meanwhile, let us hope that Les Murray gets back to writing more splendid poems. And finds ease in his life.

Comments powered by CComment