- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Celebrant of sorrow

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is the same Barry Dickins who used to write a column for the religion section of The Melbourne Times. The religion section dealt with football, and Dickins covered the waxing and mostly waning fortunes of the Fitzroy Lions, who were long ago squeezed into amalgamation with Brisbane. Brisbane was never an inner suburb of Melbourne, a sore point with followers, many of whom wore black to the game. They looked like mourners. Dickins alone could describe all the griefs that held them together. He was and is an unparalleled celebrant of sorrow. He is the bloke you want to be around when you need jokes for a funeral.

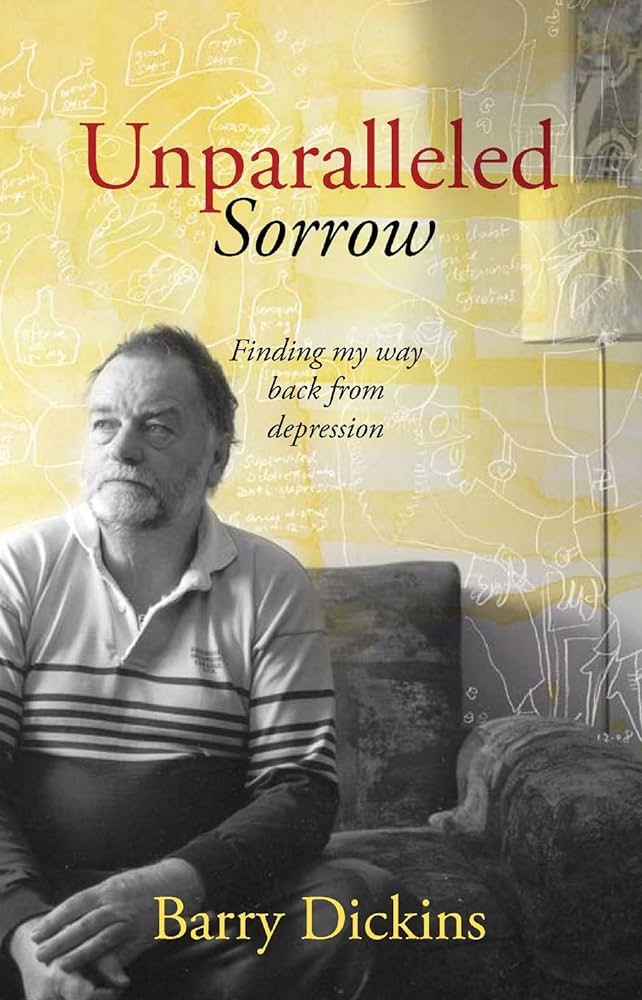

- Book 1 Title: Unparalleled Sorrow

- Book 1 Subtitle: Finding my way back from depression

- Book 1 Biblio: Hardie Grant Books, $29.95 pb, 307 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

His gags have never been just gags. Dickins’s writing has a vulnerability that adds an entirely new dimension. If his writing about football could bring the reader deep into the insecurities, secrets and saving rituals of an Australian bloke, imagine where, years later, he is going to take us when he gets onto the subject of his own depression and serious mental ill health. At the hub of Unparalleled Sorrow is a period of months Dickins spent in a Melbourne hospital around the time his marriage was unravelling.

Unparalleled Sorrow is raw. Dickins doesn’t try to tart himself up; if he is caustic about people and places around him, he spares himself even less. One of many moments in this book that linger in the imagination is a description of the way in which a nurse brought pressure to bear on an uncommunicative and angry fifty-eight-year-old to get him to have a shower: ‘She was so crude and a complete peasant, I thought in my arrogant confusion, but she was simply trying to teach me the most important lesson in life, and that is to be able to take care of your body. That before the damaged brain.’

At times, Dickins is preposterous. He says of Reservoir, the northern suburb of Melbourne where he passed his childhood: ‘in the year 2008, the only activity on Sunday was to blow your brains out. Or go to the tip and just look at stuff.’ Often he is obsessive. Dickins still feels strongly about the score he got for maths in Year 7. He can be self-absorbed, supplying reports on awards and sales figures for different parts of his writing career. Dickins has so many grievances that occasionally he begins to wear out his welcome with the reader. But Unparalleled Sorrow is a deep well. There is a fair bit of sediment on the bottom. Along the way, there is also plenty of fresh water to draw on. The reason for this is that Dickins is clearly a loving man. In many ways, he is confused by life. Yet he loves deeply and wittily.

Dickins writes beautifully about his parents, Edna and Len, and postwar Reservoir. His mother used drugs to cope; his father worked long hours as a printer. He also writes with tenderness about his thirteen-year-old son, Louis, who comes through these pages as a saint. Dickins never pretends that he is an easy man to have as a son or father, and least of all as a partner to Sarah, whose side of the story readers will be curious to hear. Louis’ tolerance of his dad is delightful and healing. Dickins only says one harsh word to his son, and that single word weighs more heavily on him than a list of other misdemeanours. His account of Louis’ birth encapsulates Dickins’s ability to turn his love into chaos. It is a great scene. There is also a memorable relationship with a 1990 Corolla during an ill-fated trip to Sydney. Dickins is a master of ratty detail.

From his voyages in chaos, Dickins creates moments of extraordinary lucidity. He describes his experience of depression:

That indeed is just what real depression is. It is flat. Like a flat bike tyre. Flat. You eat without taste or appetite and sleep meaninglessly. No matter what you do you feel unloved, unrewarded, ghastly, ghostly, invisible and the nausea of being not so much meek as without form or outline. Your past is fake and your future is all illusory.

A quarter of a century ago, Dickins shared an occasional seminar with Dinny O’Hearn at Melbourne University. It would be impossible to describe the curriculum, let alone the learning objectives or any of that other gobbledegook that in many cases now constitutes tertiary education. Yes, Dickins hated students who could make Reservoir sound like a suburb of Paris. He pronounced it Reservore. The seminar was wonderful chaos. It liberated the human spirit. Let’s hope Dickins can do for himself what he has done for others.

Comments powered by CComment