- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Keneally’s humid cauldron

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

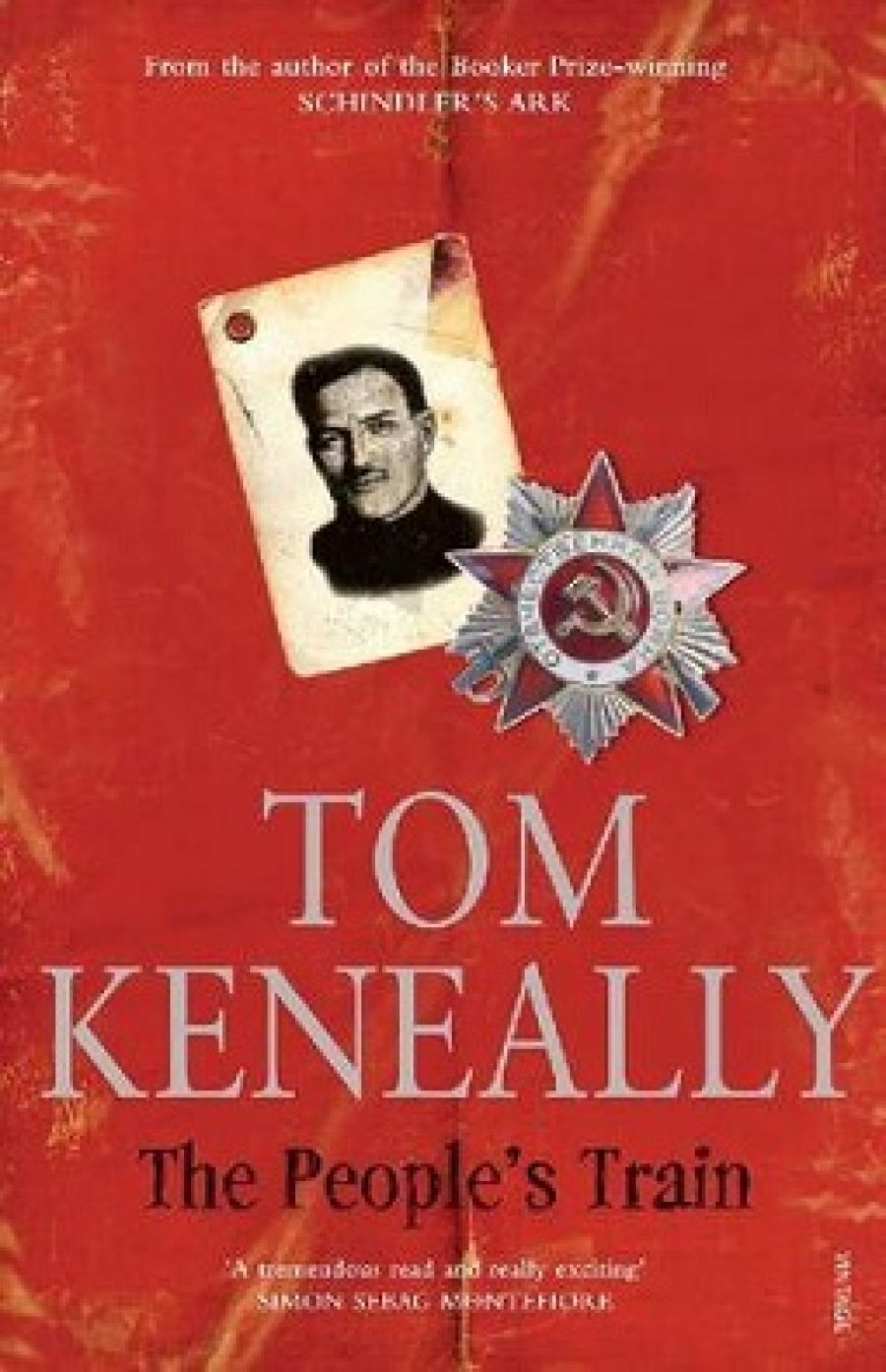

The People’s Train, a book that links Queensland to the Russian Revolution, comes with baggage. Not least, there is the mixed critical reaction Tom Keneally has endured over the decades. Perhaps most notably, he is forever to be hailed and damned as the author of Schindler’s Ark (1982). Keneally’s popularity seems double-edged: Simon Sebag Montefiore, a writer of books about Russia, breathlessly lauds The People’s Train as a ‘tremendous read and really exciting’, yet Keneally’s compulsive readability – surely cause for celebration – has somehow dented his reputation as a ‘serious’ writer.

- Book 1 Title: The People’s Train

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $32.95 pb, 408 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

But all this muddling of the man and his storytelling is, or should be, beside the point. The more interesting baggage The People’s Train carries is that of history and politics and dogma. History enthrals Keneally; he is almost rapturous in his embrace of its fictional possibilities. As he recently said, ‘I never saw Australia as separate from the world ... I could say perhaps that was because my father was absent during World War II. Did North Africa become a bit of Australia because he was there, involved in a European conflict fought along a desert coast over European issues?’ (Wet Ink, 15, 2009). The People’s Train goes back further, to the prelude to and beginning of World War I. But the themes and preoccupations Keneally identifies – not least, of Australians fighting overseas and of individuals confronting complex moral questions – sit comfortably with his insistence that Australia is an intimate part of the world, despite its sitting in isolating waters.

‘Exile is my story’, Artem Samsurov writes in the opening lines of The People’s Train. A veteran of the 1905 uprising in Russia, Artem is a dedicated supporter of Lenin. Having escaped from one of the tsar’s prisons, trekked across Siberia and then fled to Japan and thence Shanghai, Artem winds up in Brisbane in 1911, sorely needing convalescence. While this might sound like a witty anticipation of Queensland’s tourism-oriented future, placing a Russian revolutionary in Queensland is no fictional sleight of hand. In an author’s note, Keneally tells readers that there was indeed a collection of Russian exiles (of various political stripes) living in Brisbane in these years. Artem is based on a the real-life Artem Sergeiv, whose life is summarised, as Keneally acknowledges, by Tom Poole and Eric Pool in ‘Artem: A Bolshevik in Brisbane’ (Australian Journal of Politics and History, vol. 31, no. 2, 1985).

Keneally uses the outline of Artem Sergeiv to create his own, fictional Artem Samsurov. Artem quickly realises that Brisbane is no heaven on earth for workers, but rather a humid cauldron of corrupt politicians, judges, coppers and administrators. Most memorably, there is Joseph Freeman Bender, manager of Brisbane Tramways, an anti-unionist who has extended the tramline past his house and who rides around in his opulent private carriage.

Despite faulty English, Artem throws himself into helping plan a general strike and into promoting his great dream: the fundamental transformation of society. Still, he is wary of the ‘false exhilaration’ of the Australian radicals around him: ‘did these men and women want a new world, or would an extra ten shillings in their pay packet settle all their discontents?’ Whether he is marching in the streets or printing underground newspapers or picnicking, Artem attracts the attention of the authorities – and he is soon able to compare Russian and Australian prisons. Despite the language barrier, he is an orator, an agitator and an organiser; much more a doer than a thinker, although he likes telling people what they should read.

Artem’s narration is, at best, workmanlike. He writes his story as if he is peering down from a great height upon his earlier life. This gives the prose a retrospective feel. It is dulling yet apt: despite his frantic life, his politicking, the dire circumstances of his imprisonment and escape, and his influential friends, Artem comes across as a bit of a bore.

Friendship and camaraderie loom large in Artem’s memories. There are his various Russian buddies, not least his long-time mate Suvarov, who nearly gets accidentally married in Sydney, then glimpses his future life: washing dishes after dinner and becoming ‘a proud Australian subject’. There is a motley collection of Australian left-wingers, including a radical journalist called Paddy Dykes, who impresses Artem: ‘What a man – to be able to fight and orate at the same time.’ Amelia Pethick, a well-bred widow who has dedicated her life to class politics, becomes a kind of mentor and mother, although for Artem she also typifies the gulf for his Australian allies between the ideal of radical change and its practical achievement.

Artem meets the amusingly named lawyer Hope Mockridge. Soon they are working and playing together. But while Hope awkwardly parries her Establishment lawyer husband, Artem frets about being in ‘sentimental love, a delusional sickness’ best avoided by revolutionaries. Hope is perhaps the most intriguing character in The People’s Train: she is brave, opinionated, brittle and unpredictable. Yet it is hard to see beyond Artem’s fractured and ultimately bitter view of her; hard to fully comprehend her motivations, beliefs and flaws.

When the tsar abdicates, Artem heads home, with Paddy Dykes in tow. Just as the foreigner Artem narrates his Queensland adventures, so Paddy – the self-made journalist from Broken Hill – takes up the Russian story. Paddy’s narration is far more vivid and urgent than Artem’s, but so is the history he is recording. Artem remains at the centre of Paddy’s tale, the slightly listless though still impressive fish-out-of-water now transformed into a genuine leader – and one of Lenin’s key supporters.

As the Russian political scene turns messier and more violent, Paddy wanders about brandishing an English–Russian phrasebook ‘like a pop-gun aimed at my gigantic ignorance’; later, he carries a rifle. But he is also a perceptive and wry chronicler who spreads the word to Australia and beyond, and whose foreignness aids the Bolsheviks’ recruitment drive: ‘I had served my role – as the sort of statue you saw in churches acting as a spur to the faithful.’ If the extent of his eyewitnessing sometimes stretches credulity, suspension of disbelief is warranted.

Although committed to the cause and loyal to Artem, Paddy is no unthinking true believer. He is exhilarated by the Bolsheviks’ progress, but also troubled by their extreme methods (he tells himself such things are necessary in war) and, more so, by the capacity of individuals to abandon their moral code. Paddy glimpses but cannot predict the USSR’s future, whereas cameos by Lenin and Stalin subvert the reader’s natural inclination to accept Artem as a hero.

At times, multiple layers of historical context burden The People’s Train. One example: while driving in the Queensland bush, Artem and his friends pass an Aboriginal camp, prompting Amelia to speak as if on behalf of the then national consensus: ‘Sadly ... they will die out. It is our duty to smooth the dying pillow’ (italics in original). Nonetheless, Keneally builds terrific momentum by drawing on extraordinary events: the Russian Revolution and the onset of World War I. If the scaffolding of this novel is now and again exposed, that is something historical fiction can never fully overcome.

Comments powered by CComment