- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Tinge of anxiety

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Material culture is everywhere. We hoard it, we gift it, we visit it, we label it and we read it. There is little doubt that the production, preservation, use and re-use of material culture is a key means by which cultural identity is retained, protected and made available across generations. Understanding how a society inherits its cultural identity tells us a lot about that society and what it values. The danger is that this inheritance may be degraded and disenfranchised as time and fashion alter both the meaning, and materiality, of the object. If we are concerned about the stories that objects tell, we must also be concerned about possibilities for misunderstandings and mistranslations. Enter Paul Eggert and his new book, Securing the Past: Conservation in Art, Architecture and Literature.

- Book 1 Title: Securing the Past:

- Book 1 Subtitle: Conservation in art, architecture and literature

- Book 1 Biblio: Cambridge University Press, $49.95 pb, 290 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Using instances of what he calls ‘intellectual flashpoints’ – those moments in the history of a profession when debate and discussion threaten to topple existing and accepted disciplinary frames of reference – Eggert seeks, first, to establish the case for the existence of a set of common philosophical concerns among professions tasked with restoration and preservation, the heritage architect and curator, the conservator and the editor; and second, to propose ‘new ways of understanding’ where ‘emphasis falls upon the agencies for their production within … the production-consumption spectrum of the life of the work’. In short, Eggert wants to reclaim the work from the theory, and particularly from theory developed in the past four decades by ‘post-structuralist and postmodern thinkers’.

The author is certainly qualified to lead the debate. He spent more than a decade (1993–2005) directing the Australian Scholarly Editions Centre, during which time he oversaw the publication of the Academy Editions of Australian Literature series and was responsible for the eighth and final volume in the Colonial Texts Series in 2004. This book brings together his interests in editorial theories of text and textuality with his interests in the preservation of material culture.

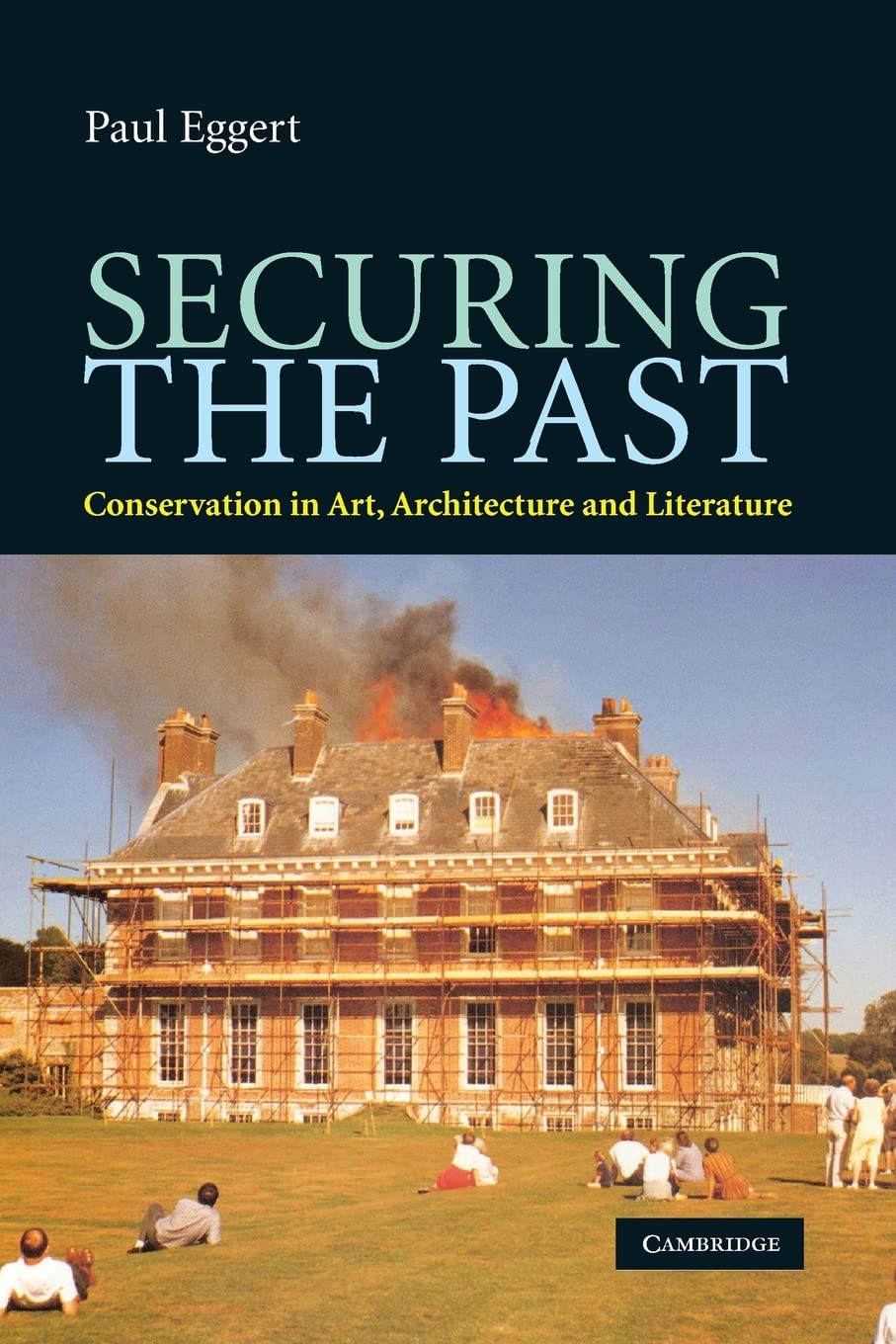

Eggert is mining a rich field. His volume is replete with examples of professional crises: the cleaning of the Sistine Chapel, Hans Walter Gabler’s edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses, the restoration of the fire-ravaged seventeenth century historic house, Uppark, and many others. As Eggert rightly claims, practitioners who engage with representation of the past are invariably struck by ‘the tinge of anxiety that securing it always has’. While the work of the conservator paring back restorations of Leonardo’s Last Supper and the editor pondering textual variations between editions of Shakespeare may appear to be disparate and more or less unconnected activities, these are, for Eggert, activities where ‘professional practitioners try to secure the past’.

Eggert ascribes the professional anxiety engendered by such work to an unsatisfactory philosophical jostling of authorship and authenticity. Dilemmas arise when claims are made that argue for the essentialist nature of authorship or the authority of text above materiality in attempts to preserve or restore a building, a work of art or a text. This uncomfortable position is, for Eggert, both unfortunate and untenable. It is unfortunate because it has led to a number of professional crises without providing a philosophical understanding of how to deal with such dilemmas, and it is untenable because, as Eggert, citing Heidegger, identifies, ‘works do not stand still … the world changes around them … What they originally disclosed is gradually lost sight of’, as they are redefined and reconceptualised within ‘frames of reference or into discourses that change what, in an important sense, they are’.

Eggert’s methodology examines ‘Contradictions between assumed theory and actual practice’, which, he claims, ‘offer[s] fertile ground, not just for those familiar, sadder-but-wiser exposures of our epistemological illusions, but for redefinitions and new directions’. While it is not entirely clear how an ‘assumed theory’ differs from an actual one, nevertheless the point is valid; there is often a disjunct between theory and practice. This disjunct can, if not acknowledged, deliver an intellectual abyss in which a profession may well lose itself.

For Eggert – and he is not alone – the root of the problem is postmodernism, which is perceived as a philosophical challenge to the underlying object and author-centred principles that have guided heritage restoration, art conservation and scholarly editing. As Eggert identifies, ‘Post-structural discursivity left no place for authorship’ and the object was lost as ‘[s]uccessive cultural or aesthetic theories … [spun] out of the one before.’ Eggert’s volume is cast as a clarion call which aims to galvanise and unify those engaged in preservation by providing a ‘new way of understanding curatorial, conservatorial and editorial dealings’.

Despite Eggert’s interest in professional egalitarianism, his path to Damascus is clearly an editorial one. The weakest chapters are the earlier ones that deal with built heritage and art conservation. Here, Eggert is clearly working at the boundaries of his scholarship. Part of the problem is that he is simply not across the current literature in conservation. Key texts, such as edited volumes in the Readings in Conservation Series (GCI), Historical and Philosophical Issues in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage (1996) and Issues in the Conservation of Paintings (2004), which could usefully inform Eggert’s volume, are not included. More recently published writing by conservators such as Salvador Muñoz-Viñas, whose assessment of the role of authenticity in conservation theory is relevant to Eggert’s thesis, or Dean Sully, whose work on the history of conservation and models of community engagement shifts the debate on ideas of authorship and expertise, are also missing.

Instead, Eggert relies heavily on comment from James Beck’s punchy volume Art Restoration: The Culture, the Business and the Scandal (co-authored with journalist Michael Daley in 1993), a number of papers from three symposiums held in 1990, 1992 and 1997, two texts on the restoration of the Sistine Chapel, and a National Gallery of London publication on Rembrandt. While material from Studies in Bibliography is referenced, the important conservation journal Studies in Conservation is not.

Another problem is that Eggert assumes all conservation is art conservation, and he appears unaware of the very different approaches that exist between the conservation of archaeological objects, works of art and archival material. The universe within which Eggert builds his arguments relating to conservation is, therefore, limited, reflecting debates that were engaging conservators twenty years ago.

Incredibly (and I write as a conservator), this is not a fatal flaw. Eggert’s enthusiasm for his journey is infectious, and his thesis is complex, challenging and hopeful. Despite my concerns with the balance of scholarship contained in this volume, it is one to be recommended. His final chapter, ‘The Editorial Gaze and the Nature of the Work’, which builds a convincing case for the ‘convergence of semiosis and bibliography’, is masterful, and the presence of it alone makes the purchase of the book worthwhile.

For those not inclined to discussions of Heidegger and Saussurean structuralism, the more practical examples that illuminate the earlier chapters provide a fascinating account of the various disputes that rocked the Anglo-American editing world from the 1950s to the 1980s. Arguments of textual authority based on chronology, intention and materiality are compared to the debates that informed the Rembrandt Research Project (and led to the resignation of most of the committee in 1993) and the editing of Shakespeare’s works during the 1980s and 1990s, where textual authority based on manuscript examination was pitted against textual authority based on performance.

Eggert is not so much interested in finding the perfect theory as in defining the epistemological transformation that is generated by the consideration of the issues. This book is well written, informative and challenging; above all, it provokes questions. Securing the Past will undoubtedly make an important contribution to intellectual debates about the decisions we make as we seek to preserve the past for the future. Eggert’s own stated ambitions for the book see it as ‘proposing a provisional solution that may help to clarify thinking when practices of preservation and conservation are being determined’. He posits the book as ‘a stimulus to debate, not as its final word’. There is so much to consider in this volume that the journey will be much more interesting than any final word. It is a volume to be highly recommended. I look forward to seeing Eggert’s work being picked up and debated in those professional forums where it can make most impact.

Comments powered by CComment