- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Tarmac capers

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Devotees of the television program Spooks may find Australian history less than exciting, but the Petrov Affair is surely the exception that confounds the cliché. Its ingredients included the Cold War, espionage, agents, a defection (hugely important propaganda for the Menzies government on the eve of the 1954 federal election) and a charming woman, the defector’s wife, who was unceremoniously hustled on to a waiting aeroplane by beefy officials from the Russian Embassy. The poignancy of Evdokia Petrova’s white shoe lying abandoned on the tarmac as the plane took off was only eclipsed by the drama of the refuelling stop in Darwin, where she was prevailed upon by Australian security to remain in this country with her husband, Vladimir. He was quite clear about his defection; Evdokia, in that pivotal moment and long afterwards, was tormented by uncertainty.

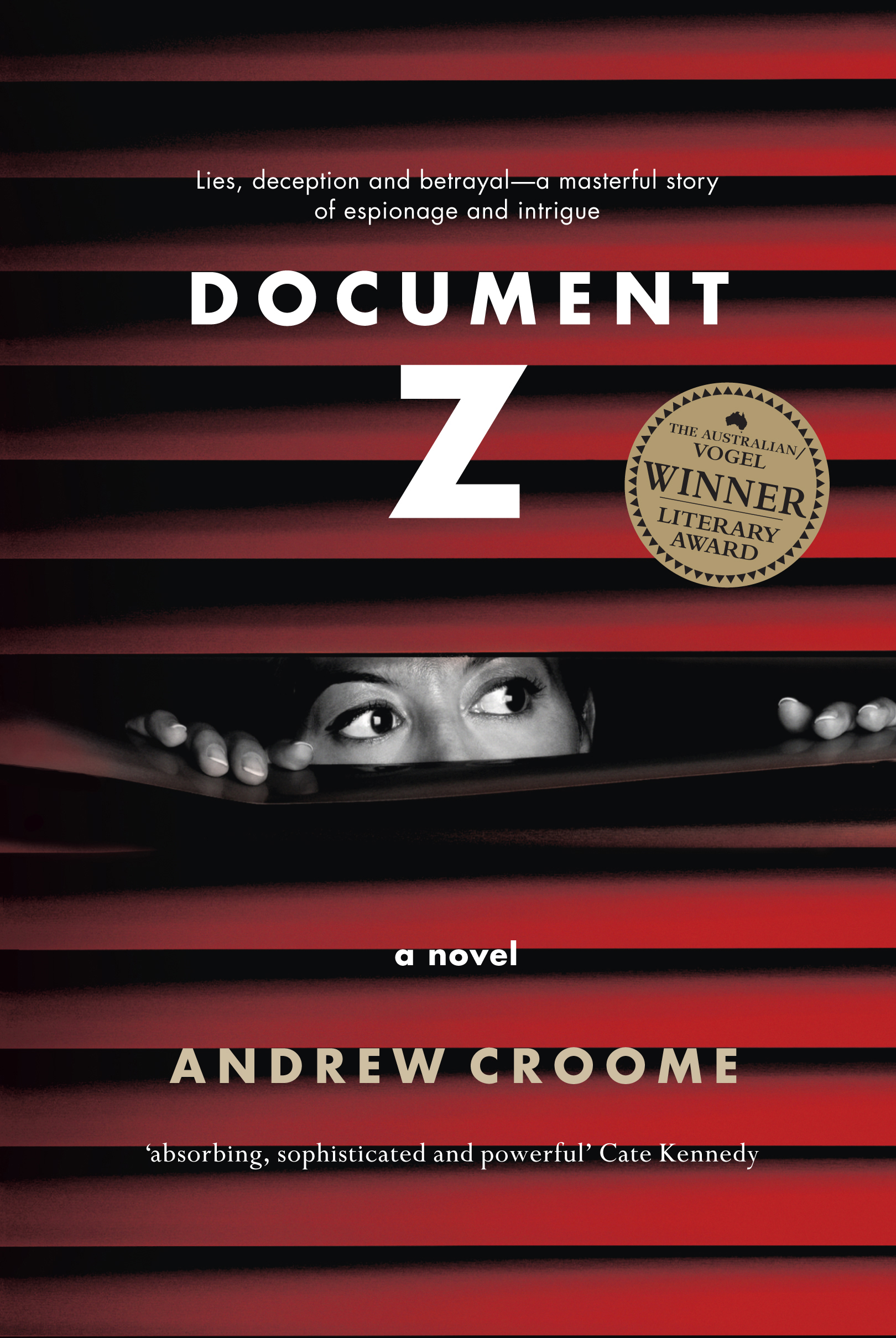

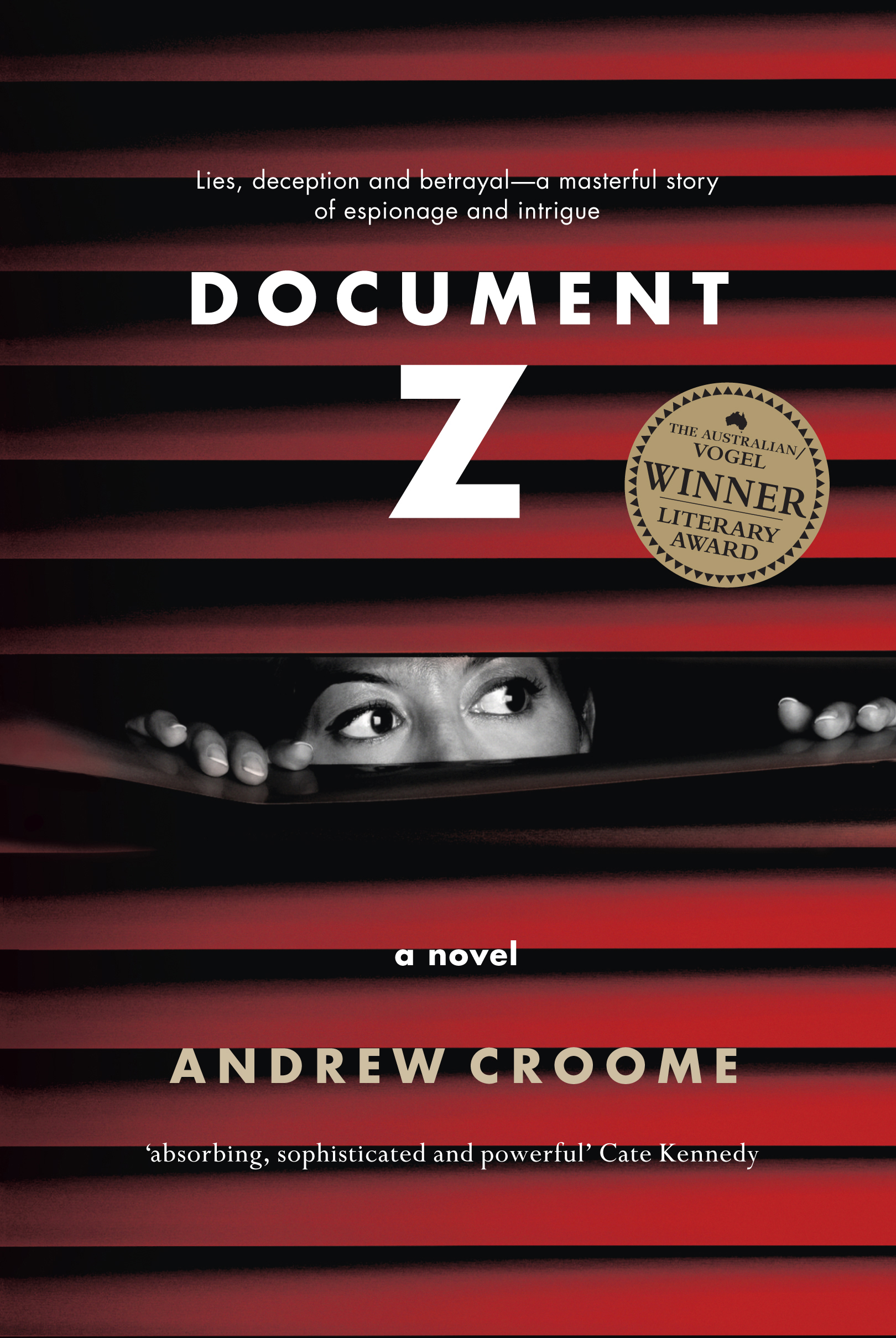

- Book 1 Title: Document Z

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $23.99 pb, 347 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Official accounts of the event, including the subsequent Royal Commission on Espionage, have of course been archived, and there are four non-fiction books on the subject: Vladimir and Evdokia Petrov’s Empire of Fear (1956), said to have been ghostwritten by ASIO’s Director of Counter Espionage, Michael Thwaites, who also, over his own name, wrote Truth Will Out (1980); The Petrov Story (1955), by the major player on ‘our’ side, Michael Bialoguski; and Robert Manne’s The Petrov Affair (1987). Now Andrew Croome, winner of the 2008 Vogel Literary Award, has produced a version classified as fiction, but which adheres to the facts as they are recorded and remembered.

The word ‘faction’ has been much disparaged of late, but we really do need a term to cover these increasingly popular hybrid works (Shirley Walker’s The Ghost at the Wedding being another recent example), in which the possible thoughts and probable conversations of real people are interspersed among things actually said, done or written. I can have no objection to a genre in which I myself indulge, but there are many people, particularly historians, who are bothered when lines of demarcation are blurred; and there is a small problem with a detail in Document Z, in which the Russian ambassador is consistently referred to as Nicolai Nikhailovich Lifanov. Apart from the fact that ‘c’ is avoided in the transliteration of Russian, meaning it should be written Nikolai, ‘Nikhailovich’ is simply not possible. The ambassadorial initials are in fact N.M., his patronymic obviously Mikhailovich – a pedantic point, to be sure, but one which prompts one to wonder if Croome got this wrong, is there anything else that passes as fact but may be inaccurate? This kind of sloppiness is a hazard of the hybrid.

On the positive side, the quarrying of dry records to reveal the driving emotions of real people – fear, greed and ambition, in particular – is the reward of this kind of novel, even when the protagonists disappoint. Petrov, who masked his spying activities with consular duties, is never seen doing work of any kind. Although Croome underlines Vladimir’s affection for Evdokia and dogs, he is mostly depicted as a dissolute, pathetically weak drunk. You may point to life in Stalin’s Soviet Union to explain his motives, but his wish to escape stems largely from bureaucratic harassment.

The equally unattractive ASIO spy Bialoguski, a more complex character, is a dubious Polish doctor desperate to make money, a name, preferably both. While courting Petrov, he introduces him to the lowlife of Kings Cross, but his own venality is based on thwarted hopes and perceived injustices. Bialoguski was sacked unfairly from the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, in which he played the violin, and should have been credited for Vladimir’s defection, but ASIO stepped in when success was imminent.

‘Doosia’, as Evdokia’s husband calls her, is the most sympathetic character in the book, and the most interesting. A specialist in encryption, she too does MVD work under the cover of secretarial activities, but unlike her (second) husband, she is affected by a sad past (a daughter who died) and by possible repercussions for her family in Moscow. More intelligent than anyone else in the vicinity, her ability to calculate pros and cons and decide her own future without being told all the facts reveals Petrov’s vapid ineffectuality. His disappearance, about which she knows nothing, puts her on a knife edge, which becomes the enthralling highlight of the book.

Though good with Evdokia, Croome depicts the ambitions of the other players without inviting much sympathy. Expounding Petrov’s, Bialoguski’s and ASIO’s respective interests in the defection tends to make the all-important ‘voice’ too judicious, but this will hardly matter to most readers. Croome has had the felicity of hitting on a story so gripping, thanks mainly to Doosia and our inquisitiveness as to how espionage really works, that everyone will want to devour it. And so they should, both for its human interest and for its reminder of one of the most notorious episodes in our national history.

Comments powered by CComment