- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Environmental Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Late in 2005, after months of delicate negotiations, the National Library of Australia announced a remarkable coup: the purchase of a previously unknown collection of fifty-six watercolours of botanical and ornithological subjects drawn and painted in Sydney in the years 1788–90, the cradle period of European settlement in Port Jackson. The significance of these paintings, unsigned and undated, had for many years gone unrecognised. The watercolours, apparently acquired as early as 1792, had been held in England over several generations by the Moreton family, the Earls of Ducie. Over several generations, their significance had apparently been overlooked or simply not understood; in time, the portfolio, though safely held, had been forgotten. It came to light in 2004 during a routine valuation of the estate of Basil Moreton, sixth Earl of Ducie. The eventual sale was negotiated with representatives of the present and seventh Earl, David Moreton, who was committed to honouring his family’s long connection with Australia on properties in Queensland. But before that, it was necessary to identify the works more definitively beyond their (then) presumed Australian subject matter.

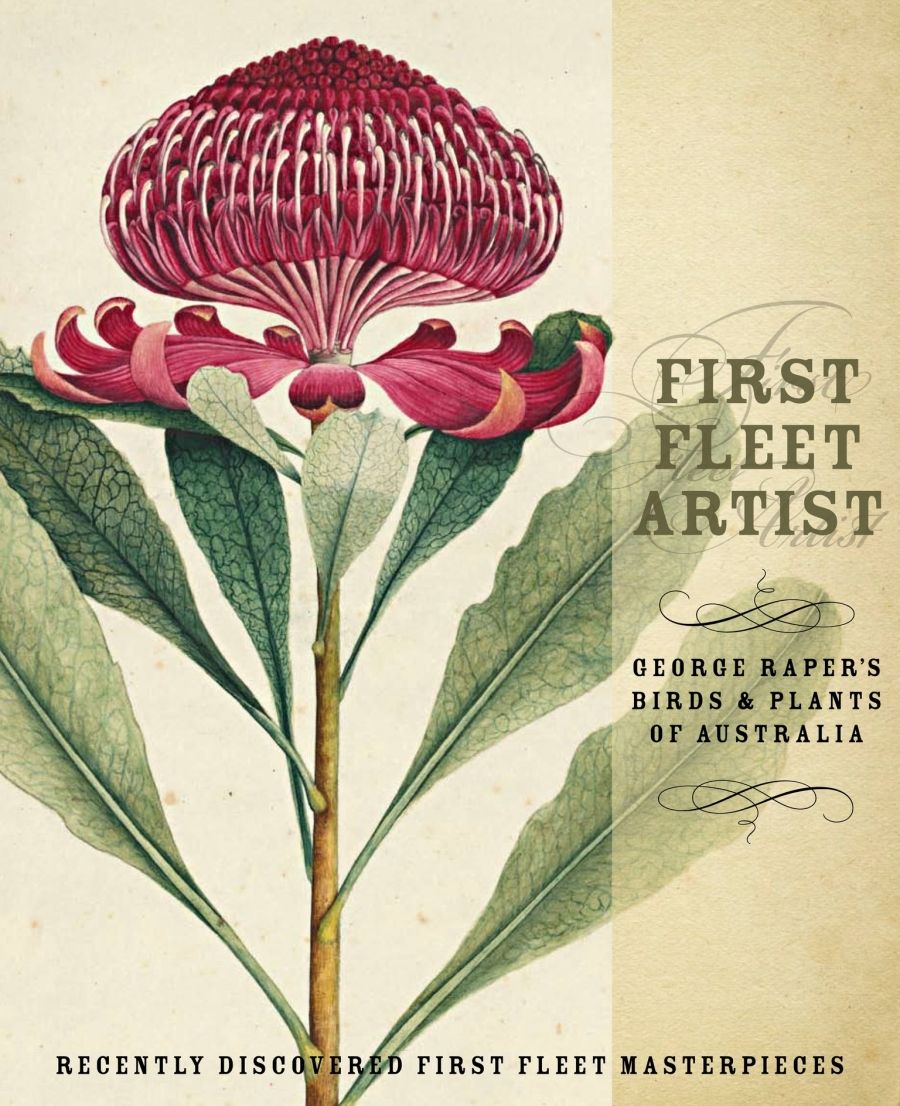

- Book 1 Title: First Fleet Artist

- Book 1 Subtitle: George Raper’s birds and plants of Australia

Examination of the portfolio by the English auction house Dreweatt Neate in 2004–5 suggested two possibilities: that the watercolours might have a connection with the First Fleet; and that they might in fact be the work of the young English midshipman George Raper (1769–96), who, as an able seaman, had sailed on board the flagship Sirius in the flotilla of eleven vessels that took the first convicts to Australia. Raper’s skills as an artist were relatively well known to scholars through existing holdings of his work in the British Museum (Natural History), the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, the Mitchell Library Collection (State Library of New South Wales) and the National Library. But those works – maps and charts, coastal profiles, maritime subjects and topographic views of ports and harbours – differed in style and subject from the fifty-six brilliantly fresh works that had come to light at the Moreton estate in Gloucestershire. By June 2005, however, the National Library felt confident enough to acknowledge a connection of the works to the First Fleet and to accept that the paintings were probably the works of Raper. It pursued its negotiations with the Moreton family and was able to secure the portfolio it has since named the Ducie Collection of First Fleet art. Having rested undisturbed and unrecognised for so long, the paintings were remarkably crisp and fresh, their colours brilliant and condition superb. But their story was as yet lacking in certainty.

The acquisition of the Ducie Collection was a triumph of collection building and enrichment by the National Library’s curatorial team. Soon after, Linda Groom, the Library’s Curator of Pictures, set out to pursue the definitive dating and attribution of the works. She concluded that they were indeed by Raper and that almost certainly they were painted at Port Jackson in the pivotal year of 1788. The story of Groom’s investigations, into the paintings themselves and into Raper’s brief life, is the subject of this delightful book, which is gracefully written, generously illustrated and handsomely published by the National Library. As she contemplated the NLA’s new acquisition, Groom was struck by how little was known of George Raper. She was intrigued, too, by the contrast between what she calls his ‘shadowy existence’ and the blaze of colour that survived in his paintings. To draw together these contrasting elements in the Raper story, Groom undertook careful research in Australia and in the United Kingdom.

Groom’s scholarship is impressive. So is her dedication in literally ‘covering the ground’ of her subject’s story: the London streets he once knew, and the remnant bushland at Mosman on Sydney Harbour where the young self-taught painter had been so captivated by Australian flowers and birds. If Raper himself remains an enigmatic personality, we now know more of his short life than we did previously. His family origins are clearer, we learn of his interests and his ambitions, and in his final Will and Testament we ‘hear’ his voice and note his sweetness of personality, his lack of pretension and his abundance of good feeling to his own loved ones. Groom reports on her investigations into the works of art themselves. She consolidates the case that now so convincingly places Raper’s small miracles of colour and observation as an important feature of the precious body of visual and written documentation that survives from the first year of the European settlement of Australia.

Comments powered by CComment