- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The Gooneratnes’ mountain bungalow, overlooking rippling tea plantations, is called Pemberley, after Mr Darcy’s mansion. A wall plaque commemorates Elizabeth Bennet’s description of it. In the style of a modern Jane Austen, Yasmine Gooneratne takes up the enduring and universal question of who will marry whom, as Vikram Seth did in his mega-novel A Suitable Boy (1994), and at similarly entertaining length. The topic is Bollywood’s favourite too, but before writing The Sweet and Simple Kind, Professor Gooneratne, a specialist in eighteenth-century fiction and poetry, had not seen the film adaptation of Pride and Prejudice.

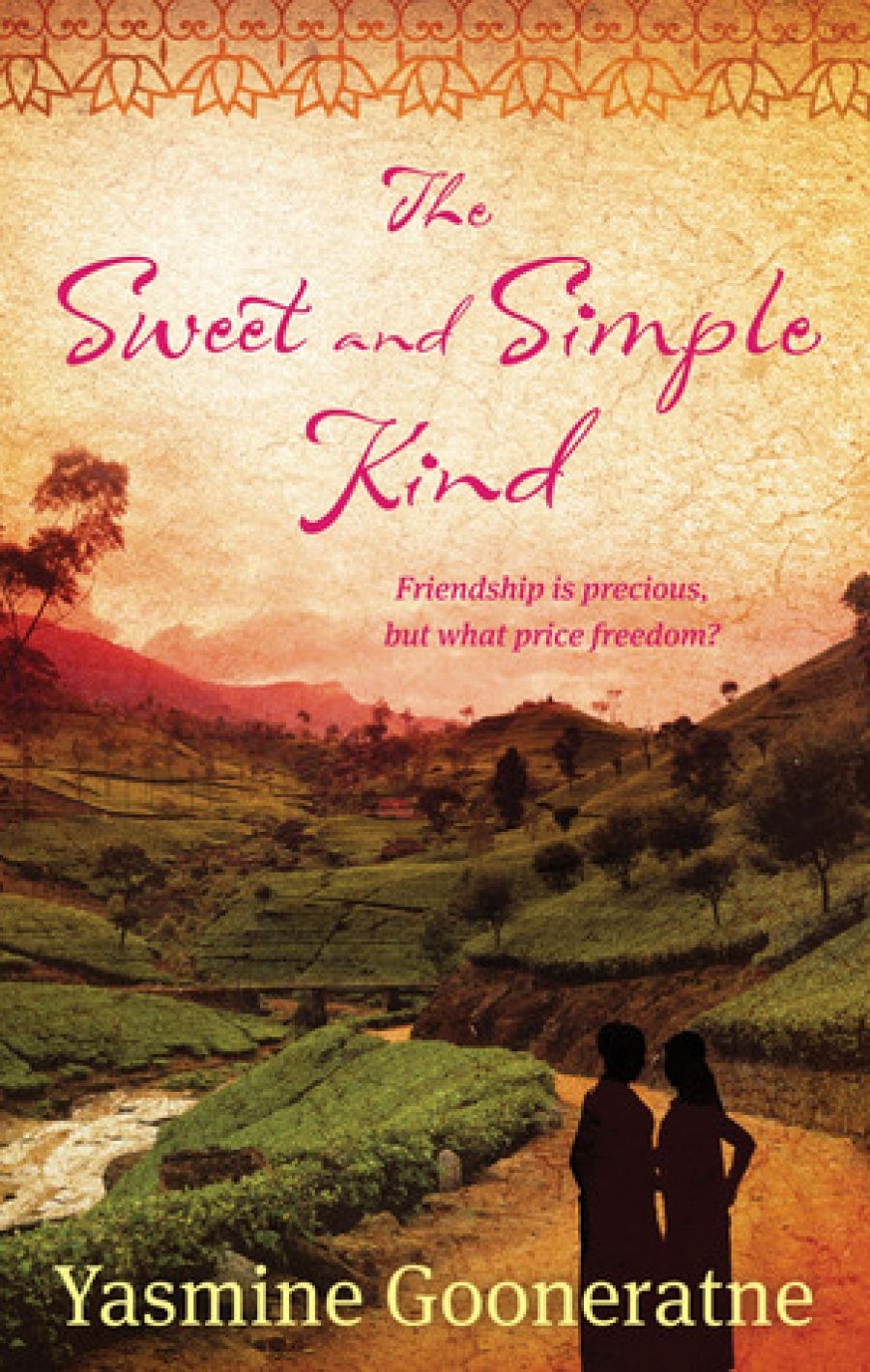

- Book 1 Title: The Sweet and Simple Kind

- Book 1 Subtitle: A novel Of Sri Lanka

- Book 1 Biblio: Little, Brown

Yasmine’s latest novel goes back to Sri Lanka in the 1930s to 1960s. Far-off Australia, for the Wijesinha family, is a prison for British convicts, a place of exile for a disgraced relative, and unthinkable for emigration. A Wijesinha elder tells his daughter she belongs to ‘a world so advanced and civilised that it doesn’t give a damn about the world outside it’. World War II no more disrupts their comfortable, civilised lives than the Napoleonic war disturbed the Bennets’. The Wijesinha men are educated in England and collect English books, and the children read voraciously. One wife, the elegant Helen, a ‘Tamil Hindu from India’, does embroidery and obeys her husband for as long as she can stand it; another, the Singhalese Soma, trains schoolteachers, gossips and tells her husband what to do. But after independence in the 1950s, anything goes: ignorant provincials become members of parliament, Singhala becomes compulsory in schools, low-caste students are admitted to university and some girls refuse arranged marriages, while others want to marry Indians or Tamils. Two of the Wijesinha cousins, Latha and her close friend, the improbably-named Tsunami, are excited to be ‘living in a free country, at the beginning of a new age, in which every possibility is within our reach, and nothing exists that youth, energy and idealism cannot achieve!’

How wrong they are. Latha’s tutor, Mrs Phillips, lives by her principles with her Marxist Tamil husband in a low-caste farming community until they are driven out by racism. Tsunami speaks her mind in response to diatribes about race and caste from her college principal, but her hopes of marrying a Tamil from Jaffna are dashed by her politican father, who declares the world to be full of criminal characters, ‘most of them niggers and Jews’. Later, her elder brother disinherits her when she wants to marry an Indian. This is the way society thinks, says Latha, adding despairingly, ‘this is real life, not Pride and Prejudice’.

Even at university, respectable girls don’t speak in class, don’t drive and dare not be seen alone with a boy. Respectability is a religion, the patriarchs are its high priests, and their standards are double. Helen’s departure for Sydney with a Jewish Australian is tantamount to sacrilege, yet the plantation owners have local girls procured for them and their male friends, just as the British used to do. But it is the social-climbing Moira who knows how to work within the system, and gets herself elected by appearing to be cultured but not ambitious. Her cultural ‘piccadillies’ bring out the satirist in Gooneratne, as when Moira talks about the ‘ballot’ dancers painted by ‘De Gass’, and informs a bemused Indian diplomat that ‘music has charms to soothe the savage beast’.

As in her Australian novels, some of Gooneratne’s characters are identifiable – or their characteristics are. This novel, taking its title from Eartha Kitt, evokes the period when Pitman’s shorthand, Morris cars, radiograms and tele-phones at home meant modernity. (I am not sure that expressions like ‘that figures’ or ‘rent-a-crowd’ were current in the 1950s). No matter how atmospheric, a mere memoir-asfiction would not have been nominated for the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize and the Dublin Literary Award. So what is its strength?

Like all satirists, Gooneratne uses the past to comment on the present. Filling his pen with Quink during the 1958 Emergency, Herbert Wijesinghe – I almost called him Mr Bennet – writes sadly: ‘The age of our innocence is past.’ The causes, he believes, lie not in Sri Lanka’s colonial history but in the people’s prejudices. A Burgher academic who has left for London puts it more explicitly: ‘I don’t believe race relations there can improve. As long as both a caste system and racial hatred are built into the consciousness and the upbringing of the young, the most we can hope for is an attempt to control their consequences.’ Fifty years on, Tamil separatists and the Sri Lankan army fight to the death in the north, and journalists are shot dead in Colombo. Meanwhile, the dilemma identified in the novel is still unresolved.

Comments powered by CComment