- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Susan Varga’s latest novel, Headlong, is set in Australia in the opening years of the twenty-first century, with the Tampa episode and detention camps as background. This setting reflects Varga’s own work with refugees and the Nazi camps of her family’s Hungarian past. Headlong relates the downward spiral that the previously indomitable Julia undergoes after the death of her husband. Her two children – the narrator, Kati, and her brother – try everything to restore their mother to physical and mental health, but Julia is adamant: life is hell. The fact that she escaped the Holocaust with her daughter and survived the horror of those years makes the story all the more poignant and distinct from similar stories of grief. Why has this loss defeated her, when she has met every other challenge in life? Has it unlocked the hidden pain of earlier years? This question, and Kati’s ensuing grief and sense of guilt, sustain the novel.

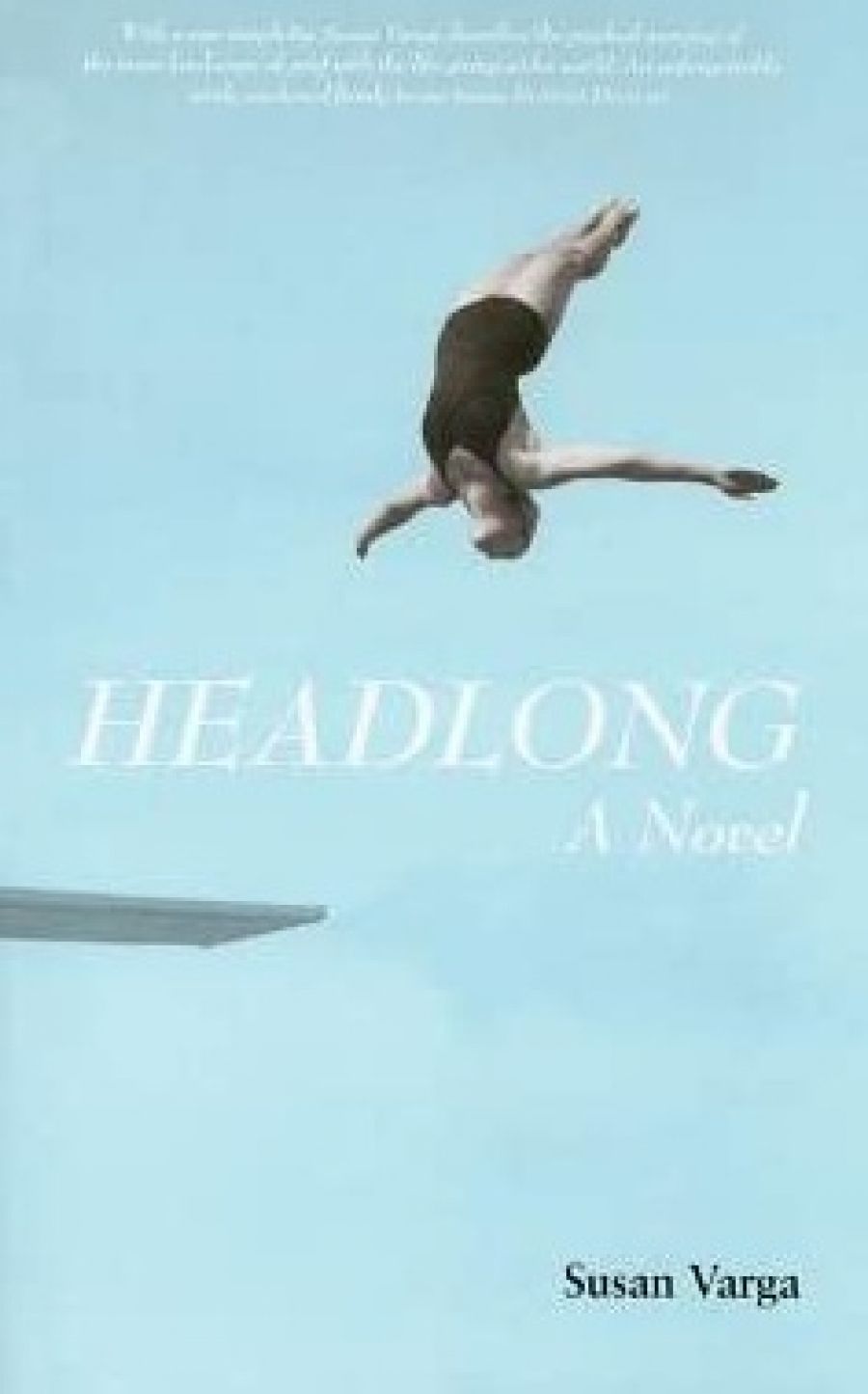

- Book 1 Title: Headlong

- Book 1 Subtitle: A novel

- Book 1 Biblio: UWAP, $27.95 hb, 230 pp

Headlong is a study in grief, firstly of the mother and secondly of the daughter. Kati’s mourning is sidelined by her mother’s, until the wheel turns and she too must come to terms with loss and the way it affects her relationship with her brother and her partner, Gill. It is an extended reflection on the darker side of life, where loss and loneliness isolate the individual and make them incapable not only of loving but of being loved. The issues of depression and voluntary euthanasia jostle against a background of hospital corridors, lonely Australian beaches and relationships that falter under the weight of recrimination, isolation and shame.

Varga entices the reader with suspense, emotion, the multifaceted character of the mother and the writing itself: insistent, sparse, short sentences that click over in anguished bursts; dialogue that is stark with pain. The anguish is almost too realistic. The momentum is exhausting and our patience threatens to run out for Julia, who will allow nothing to stand in her way. Kati’s frustration is infectious:

But I’m also angry with her, so angry that my ambitions to be a good daughter are in ruins. I’ve tried to advise, sympathise, act on her behalf, plan her future. But nothing has worked. Nothing has worked. She goes her own way. Her unconscious will, a thousand times stronger than the one she is aware of, is made of iron and steel and metals from the mouth of hell.

Metaphors of swimming – hence the title – create a lyrical theme in the brief prologue, which sets up the relationship between Kati and her mother. We see Julia, well into her eighties and still powerful (‘a tempest of a woman’), while her husband is alive. The portrait of the couple, drawn largely through dialogue, is compelling. The tension that exists between the stubborn mother and her well-meaning daughter prickles in their conversations. The smattering of Hungarian endearments adds a sense of the strong familial ties that override all other considerations and petty differences.

On this rollercoaster ride, there are occasional let-downs: after a tense build-up to Julia’s ECT treatment, we are not told how she comes round from it or how her daughter copes. We crave every detail in this eyewitness account. On the whole, Varga gives us a multifaceted look at the moral and emotional confusion that death creates.

Headlong reads like a memoir. This impression is based at first on the writing, a rush of adrenalin-fuelled angst. The narrator is so close, the product of her thousand-word-a-day goal presented for us to read. Varga’s childhood and her present situation are in many respects identical to the fictitious narrator’s, and her acclaimed biography of her mother, Heddy and Me (1994), bears that out. In Headlong, it is the mother’s story that resonates most strongly, this woman who crackles with life in its last frantic stages and dominates those around her to the end. Her flat is an extension of her personality.

By contrast, the character of Kati has none of her mother’s clarity. Although she is ‘well into her fifties’, she seems much younger, and we have no clues as to what she looks like. Her partner is identified by the annoying habit of pushing her red glasses up her nose. More physical details of their life would have grounded the story and made it easier to switch the reader’s sympathy from mother to daughter. Perhaps the partial anonymity of the narrator is intentional. It is the story of everyone who has been through the slow slog of grief, when only time will heal – if we let it.

Comments powered by CComment