- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

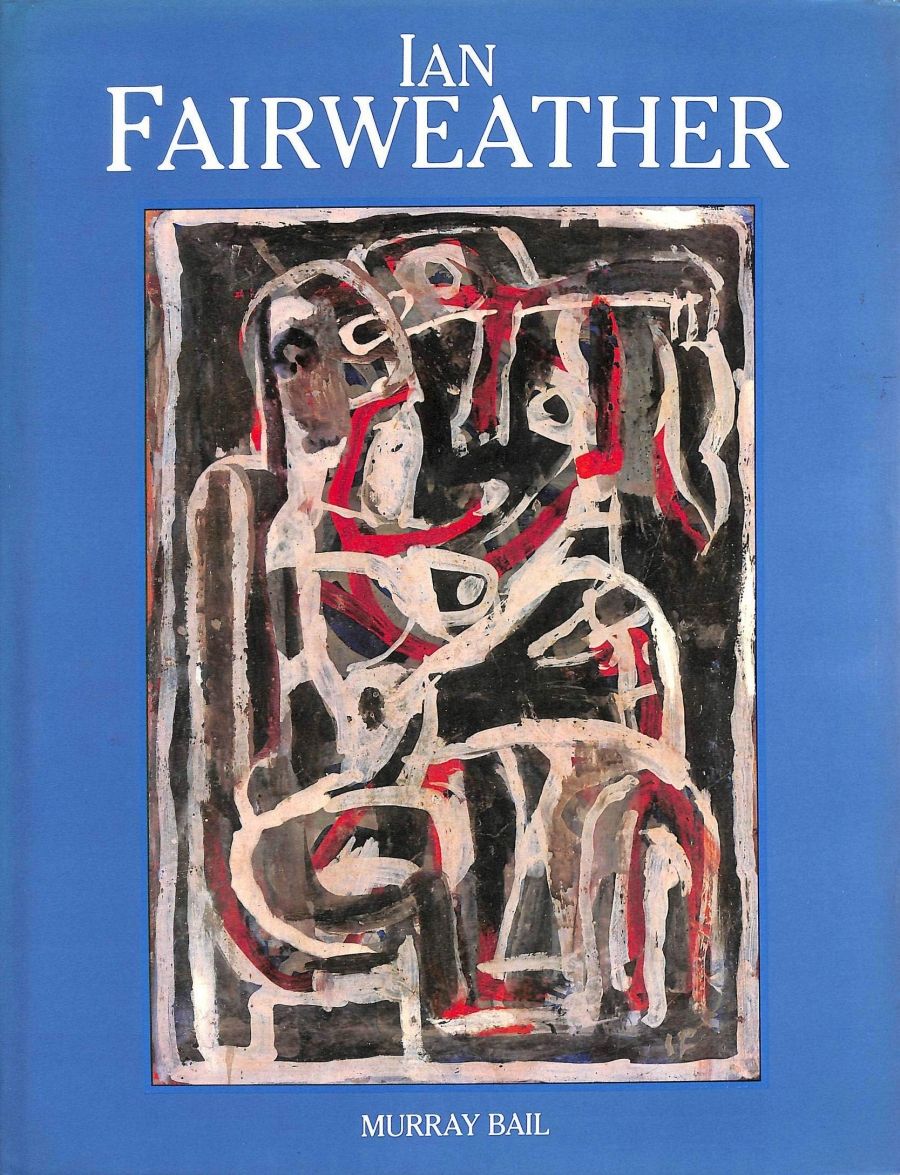

‘A large part of the beauty of a picture,’ Matisse famously decreed, ‘arises from the struggle which an artist wages with his limited medium.’ Struggle is the dominant motif in Murray Bail’s study of Scottish-born painter Ian Fairweather, first essayed in 1981, now refashioned, updated, and handsomely repackaged.

- Book 1 Title: Fairweather

- Book 1 Biblio: Murdoch Books, $125 hb, 280 pp

Any youthful dalliance with oils, especially oil on canvas, had yielded, by the time Fairweather settled in Australia, to working all but exclusively in ink, watercolour, gouache and (when it became available) synthetic polymer paint. These materials were applied to fragile cardboard or cheap paper – sometimes newspaper – which might then be mounted on hardboard or crude plywood. For someone acknowledged early on in his career as a master colourist, Fairweather was unusually restrained in his range. He eschewed any but the merest peeps of green, even in the tropical landscapes he did around Cairns in 1939, and increasingly favoured shades of grey or earthy, ochreous hues, picked out here and there with indigo, pale pink, black or dulled white. This makes all the more shocking the odd heretical burst of vivid yellow or Poussinish blue. The finished surface at which he aimed was studiously dry, rough, harsh: the antithesis of Gauguinesque-lush or Smarty-smart.

The immaculate sheen of a classic Jeffrey Smart is one of Bail’s bugbears. (‘What is the point,’ he asks, in such ‘perfectly primed canvases and top-quality oil paint?’) He is prepared to concur with Bernard Smith that Fairweather was at one time nearer to Gauguin in his inclination to ‘escapism’ or nostalgia in his choice of themes, images, figures, scenes. But Bail is keen to trace a new artistic trajectory following Fairweather’s mad, heroic, lone voyage by home-made raft in 1952, and his subsequent commitment to a hermit’s life in a makeshift hut on Bribie Island, off the Queensland coast. Fairweather had always been wary of his art’s appearing ‘too sweet’, too obviously pleasing. In his later work, as Bail tracks its progress, he tried even harder to ensure this by marginalising or obscuring any figurative or scenic elements – if never quite managing to obliterate them. The more abstract the better, just as the rougher the better, by Bail’s lights.

Fairweather’s resort to, or committed embrace of, the most impoverished materials for art was complemented by a rigorously austere style of life, largely indifferent to the material rewards that could have started coming his way as his cult status grew. ‘Is it so important to have a show – anyway?’ he had asked an English patron of his work as far back as 1935, when his escapist impulses had taken him to China. For the rest of his ‘career’ (can we even use that word in this context?), he remained in retreat from the promotional circus that was becoming de rigueur for any artists who hoped to make a decent living out of their work. Conventional standards of decency or sociability did not concern him.

There were to be several shows of varying magnitude over the next forty years of his life, but he only personally appeared at one of them. He was not even particularly concerned with what his fellow artists were creating. From his fastness on Bribie, he had probably never heard of the various artistic parallels or ‘influences’ that critics were fond of invoking in discussing his work. This Odysseus figure, as Nicholas Jose has cannily characterised Fairweather in an essay on his earlier wanderings in the East, risked turning into a precursor of the eponymous drowning man of William Golding’s Pincher Martin (1956) before settling down to replicate any number of stranded souls, unaccommodated men out of Shakespeare (The Tempest, as well as Lear), Defoe or Beckett.

Fairweather had heard of, and enjoyed reading, Samuel Beckett; also Thoreau’s Walden, the recluse’s vade mecum. But he did not self-consciously follow the paths they delineated. There is no easily extricable identity behind those mythological emanations that we sense in him. All but obliviously he lived out such myths, and they made him what he was. His studious solitariness and asceticism, the extent to which he was prepared to maintain the level of struggle in his daily round, were a life choice of sorts, but they were also a necessity for his art. They were what made him and it sui generis.

Murray Bail is to be congratulated for so effectively recapturing in words the physical exertions and mental agitations involved in Fairweather’s engagements with brush and paper, for rendering so vividly the behaviour of painter and of paint that combined to produce such a distinctive oeuvre. In his marvellous book What Painting Is (2000), James Elkins rebukes some of his fellow art historians and theorists for ignoring the medium of painting in their concentration on questions of iconography or social context, for separating meaning from means. That charge could never be laid against Bail.

Perhaps only a fellow artist, if in a different medium, could so evocatively recreate the creative act, its challenging circumstances and its beautiful outcomes. There is no undocumented hypothesising in Bail’s Fairweather of the sort that troubled some reviewers of Peter Robb’s biography of Caravaggio (1998), and no fictionalising of the kind that Peter Ackroyd ventures on in some of his hybrid portraits of artists and writers. But there are unmistakable touches here of the novelist in Bail that we would find in no routine scholarly account: a narrative that is broadly linear but not afraid of digressive fragments and other unsettling subversions of chronology; a style that is soberly lucid yet shot through with quirky, elliptical, arresting phrases: ‘under the penumbral thumb’, ‘porcupined with guilt’, ‘the shuddering gait of a buffalo’, ‘a mangrove of misunderstandings’, ‘a swathe of ecclesiastical mauve’. These may be ‘effects’, but they are not affectations. They signify a sensibility totally in tune with its subject, and quite as distinctive: sui generis, indeed. I can think of no other treatment of an artist quite like it.

If you didn’t know of the earlier version of this book (Ian Fairweather) you might even be pardoned for assuming from its title that Fairweather is Bail’s latest novel, in the terse tradition of his two best-known fiction titles, Homesickness (1980) and Eucalyptus (1998). The change, of course, is designed to differentiate the two versions. It is a slight enough change that duly reflects the largely cosmetic alterations to the original text: minor deletions, additions, rearrangements, emendations. There is a scattering of completely fresh paragraphs incorporating research on Fairweather carried out in the intervening years by Bail and various others; and he has completely rethought and rewritten the sections on Aboriginal influences (now downplayed – rightly, I think). And then there are the changes to the reproductions: a sizeable increase in overall quantity (though several of those included in the first version of the book have also been excised), and a lavish enhancement in their quality and presentation.

While these revisions and refinements may well merit a change of title, I doubt they justify the respective claims of the blurb, the media release and the author’s new preface that Fairweather is ‘an entirely new study’, ‘a complete rewrite’, ‘a new book’. I am not sure the author himself would approve of the blurb’s further claim that his study represents ‘the definitive life and work’ of the artist. A more detailed biographical chronicle had already appeared three years prior to his first edition: Nourma Abbott-Smith’s Ian Fairweather: Profile of a Painter (1978). Bail’s enterprise was always more idiosyncratic and venturesome, and he has remained attached to its rougher edges, as if in homage to his subject. (Personally speaking, the former editor in me could have done with the removal of just a few of these, mainly inherited from the first version: minor syntactical glitches, and the odd error: ‘Christopher Woods’ for English painter Christopher Wood).

Personally, too, as the prospective biographer of Fairweather’s fellow-artist Donald Friend, I find puzzling Bail’s curt dismissiveness of Friend whenever he mentions him. Even Smart gets off more lightly. I wouldn’t want to question the implied greater claims for Fairweather’s status as an artist; but Friend and Fairweather were rather more alike – and liked each other more – than you might imagine from their art or their outward personae. As fellow ‘Odysseans’, for one thing, compulsive voyagers: a sure antidote for each to the sin of ‘parochialism’ – about the worst sin of all in Australian art, as Bail sees it. Loving Bali as passionately as Fairweather did, Friend could also recoil from an ‘excess of green’ there. Though no hermit, Friend increasingly yearned for solitude in order to practise his art; though never the party animal, Fairweather came to enjoy what company came his way on Bribie, including that of Friend’s. They kept up a lively, empathetic correspondence after Friend’s pilgrimage there, and the Friend diaries have several Fairweather letters pasted into them. These sources help illumine various enigmatic aspects of Fairweather’s sensibility, from his sexuality to that aversion to green, yet Bail shows no evidence of having used them in the years since they became publicly available at the National Library.

The saddest inheritance of Bail’s updated edition from the earlier one might appear to be the concluding sentence: ‘Due to the nature of things, reticence and distance on Fairweather’s part, the rest of the world scarcely knew, or even knows now, of his existence.’ But even if that remains the case after this refurbished version from an international publisher, we may wonder, consolingly, whether Fairweather himself would be too fussed. If struggle is the point, the journey, not the survival, matters.

Comments powered by CComment