- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Since her début in 1971, Pam Brown has been a consistently intelligent and engaging presence in Australian poetry, if too often under-represented in those reputation-establishers, the anthologies. One pragmatic reason for this may lie in a further element of consistency, the formal structure of her poems. Poems that spin their way down the page, resolutely short-lined, or ones that fragment lines and thought into zigzag patterns across the breadth of the page, are faithful to the characteristics of the New Australian Poetry celebrated in John Tranter’s 1979 anthology of that title. They are characteristics that Brown has honed finely over the years. They are also, from the point of view of anthologists and, more powerfully, their publishers, wilfully heedless of that most brutal constraint, the number of pages available for any given anthology.

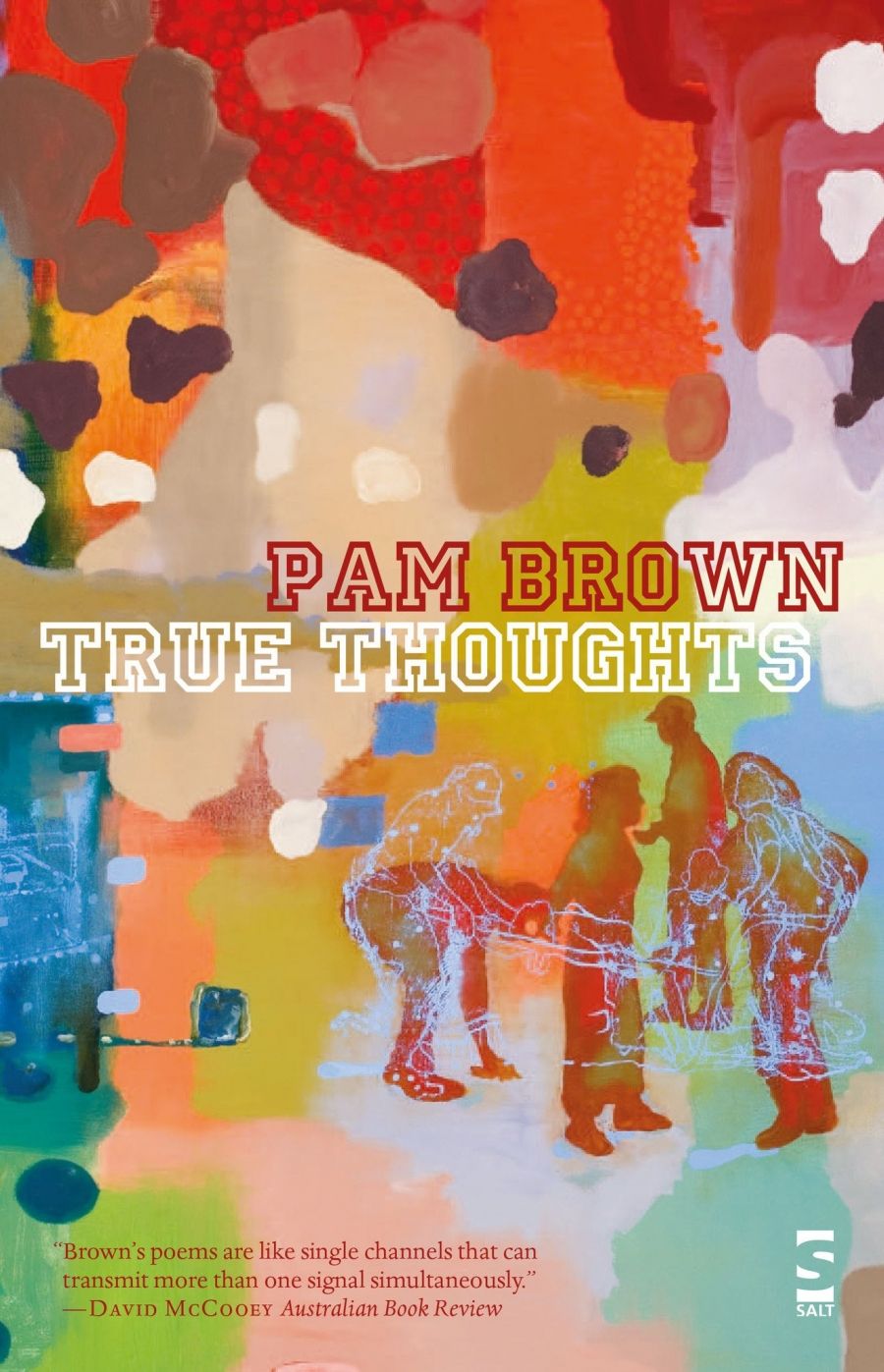

- Book 1 Title: True Thoughts

- Book 1 Biblio: Salt Publishing, $35 hb, 80 pp

Space can be more generously provided in a dedicated volume, especially if elegantly produced, and in reading this complete collection one becomes aware how much the form allows for the shifts of stance and tone, the play of ideas that lend complexity and shading to an air of spontaneity, almost chattiness. The latter is manifest in the snippets of conversation, the jokiness, the de-solemnising of high culture references found, for example, in ‘John T phones – / this cloudy gloomy / early summer day / is ‘like the fifties’ he says. / everyday? / miserable childhood? / photographic weather memory / à la recherché du temps inclément’.

These lines from ‘Peel me a zibibbo’ may look as if Brown is simply following poets such as Tranter, John Forbes and Laurie Duggan in introducing fellow poets and other contemporary writers into their poems in a practice presented as radical, though harking back to the poetry of classical Rome. But Brown’s inclusion in the group would have been problematic, fraught with feminist issues of exclusion that inevitably concerned a woman writer in the 1970s. These are re-invoked when this poem ends with the request to a list of male friends, poets, singers, artists – even Shakespeare – to ‘peel me a zibibbo / would you / one of you guys?’ Apart from the title itself, the allusion to Peel Me a Lotus (1959) and the troubled career of Charmian Clift is suggested (obliquely enough) by the explanation in the notes that a ‘zibibbo’ is a grape grown in Sicily (an Italian rather than a Greek island).

This obliqueness, refusal of the overt, avoidance of the ‘big questions’ and large gestures marked the Sydney poets of the 1970s. It was a matter of how to think as well as how to speak. Brown seems to embrace the condition in lines such as ‘as / the new / gets / newer / I get / no chasms, no abysses / I get / crevasses / of doubt’ (‘Augury’); or ‘under a nasty sky, / rhetorical uncertainty / dogs me’ (‘Existence’). But this is not the only note struck. Commentators emphasise, and rightly, the ironic eye with which Brown regards the inconsistencies and futilities of human behaviour: ‘we rally for peace / we play with the kids / the armada heads for the gulf’ (‘Amnesiac recoveries’). Nor are the poet and her activities, or lack thereof, exempt from that gaze.

Is it, after all, possible in this postmodern era to read True Thoughts as other than an ironic twist on the kind of confidently edifying titles beloved of the Victorian era? Aren’t the only true thoughts nowadays those that are Janus-faced, aware even at the moment of conception of being ambiguous and ambivalent, always potentially self-contradictory about emotions, evaluations, even facts?

This doesn’t mean we must be ‘sherbet-brained, / fizzily beginning to feel / like Nietzche spake – / nothing is worth anything’. These ‘truths’ don’t cancel each other out: they coexist. Take the question of politics, which figure largely in several of these poems and account for much of the nastiness attributed to the sky of ‘Existence’. Not so much sexual politics as the politics that make wars imminent set bombs and refugees in motion. We might think Brown’s attitude straightforward enough if we judge solely on this passage from ‘Amnesiac recoveries’:

last century ended

after frightening

almost everyone

with various versions

of totalitarianism,

too much to be ashamed of

as I write as you read

the USA

is bombing

_____ _____ _____

(please fill in the blank spaces)

In ‘Worldly goods’, however, we find weariness with ‘ergonomic-chair activism’ breeding a positive desire to create blanks by deleting unread all the e-mails soliciting for causes, while in ‘No action’, Beckett’s dictum ‘that politics is useless, / & talking politics, worse’ is enough to defuse an initial impulse to fill in the blanks, ‘combat complacency, / BE political, be GREEN’ – that is, until Beckett re-emerges at the end of the poem as a man who, under the Nazis, ‘forwent / the apolitical’ to fight with the maquis, not for the abstraction of ‘France’ but for the liberty of friends, becoming ‘a person, / any artist or poet / could only hope / to be as / courageous as / or, at most, as definite’.

Brown might not, then, be pleased with praise of her consistency. In these poems, it is contradictoriness, rich source of wit and irony, that lies at the heart of thinking truly.

Comments powered by CComment