- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Patchwork identities

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

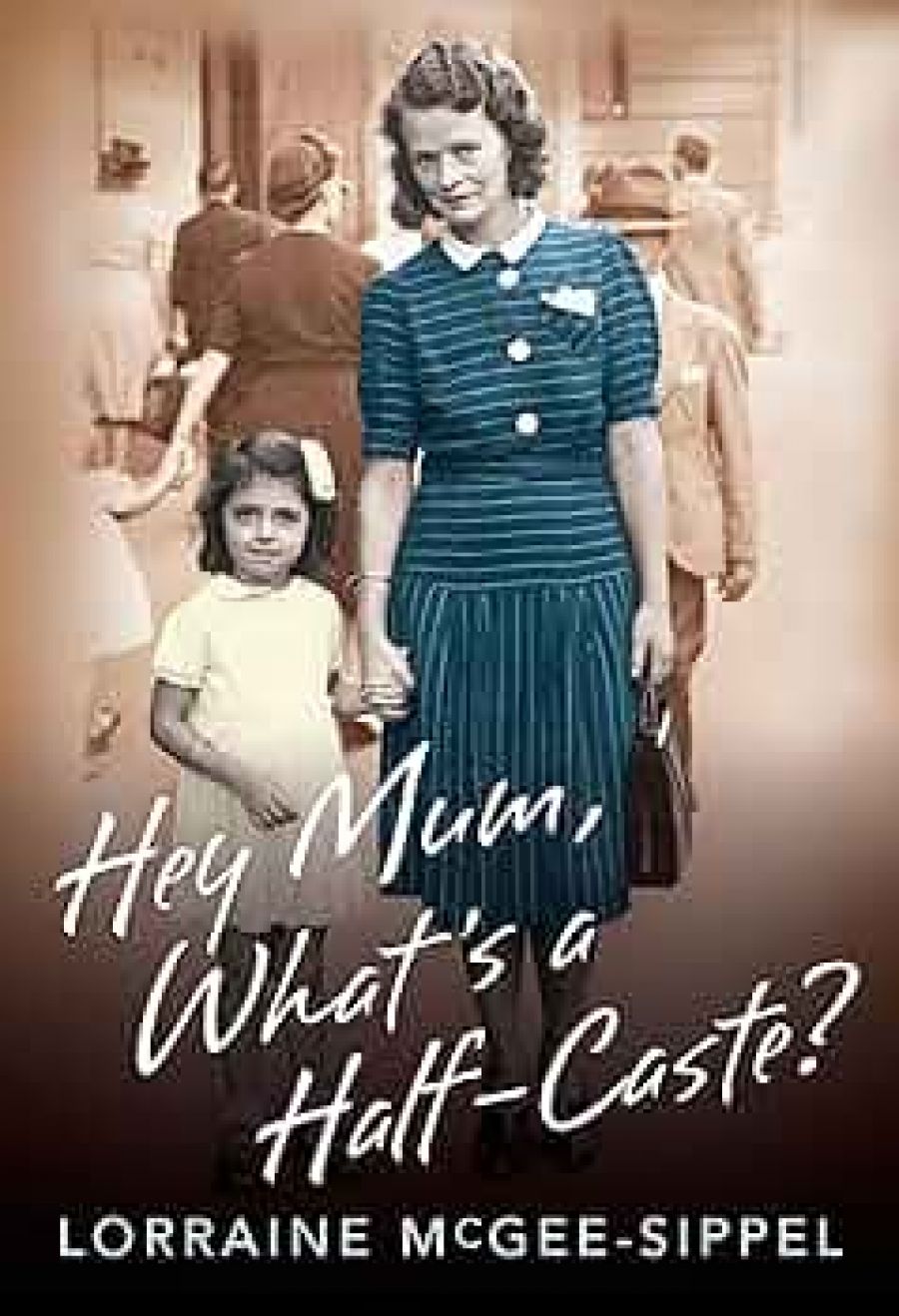

The title of this memoir and the cover picture, showing a pretty girl with brown skin and hair and dark eyes walking along an urban street hand-in-hand with a neatly dressed white woman, captures the theme of uncertain identity. The story begins in mid-twentieth-century Australia, when, under the government’s assimilation policy, children of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent were still being removed from their families. Lorraine McGee-Sippel was not stolen from her family by the authorities, but was surrendered for adoption by her eighteen-year-old mother.

- Book 1 Title: Hey Mum, what’s a half-caste?

- Book 1 Biblio: Magabala Books, $24.95 pb, 289 pp

‘Toots, your mother was white but your father was black. He was a Negro. The social worker said we’d be sorry for taking you, and that you’d have to be checked out by a social worker before you had kids. She said you could have throwbacks and your husband might think you had been playing around.’

He responds to her shock at this news by adding: ‘You see, Toots, no one else wanted you, but Mum and I did.’

A feature of Western autobiography, according to Jerome Bruner, an American psychologist and narrative theorist, is the recurrence of turning points, when a crucial change in the protagonist’s story is attributed to an internal or external event. These, he suggests, are moments of individualisation, when people free themselves in their self-consciousness from their history and the conventionality that makes them merely one of the crowd. I counted at least eight turning points in this story. In the second half of the book, after Lorraine is reunited with her natural mother and begins to retrace her Aboriginality, they come at a breathless pace. The first conscious awareness of a dissonance in her identity occurs when Lorraine is seven, and her classmate at the small bush primary school hisses in her ear, ‘You half-caste’.

This is a story written from the heart by a courageous and feisty woman who has overcome the traumas of feeling unwanted, of mistaken identity, of broken and damaged relationships and many tragedies in her large natural family before and after she is reunited with them. Not least of her heartbreaks involves the discovery that her natural mother has been so damaged by her incarceration as a fourteen-year-old in Parramatta Girls’ Home that a healthy filial relationship is not possible.

On one level, this is a detective story, driven by the narrator’s determination to reconnect the pieces of her family patchwork. Thus, the narrative is concentrated and anecdotal, especially in the second half. The storyteller’s voice is clear and vivid, and the narrative is well constructed, though it is a challenge to keep up with all the family members who are introduced and the history of their lives in regional New South Wales and Victoria. The details of Lorraine’s encounters with her extended family – first her mother’s, then her grandfather’s, then her white father’s – accumulate, until the reader is left with a blurred impression of battling families of ten and twelve children scattered around country towns. I wanted more detail, texture and back-ground in this section. The text is supported by a collage of relevant maps at the front of the book and by a family tree that introduces the closing chapters. There are also some engaging photographs, beginning with the institution where Lorraine was placed as a young baby before her adoptive parents took her home and ending with some recent triumphal scenes from her life as an older woman, awarded the title of Yabun Elder of the Year (2008), and an activist in the cause of reconciliation.

There is enough material here for two books. I found the childhood section moving and memorable, with many scenes sketched in brief but vivid, sensuous detail. When Lorraine is eight years old and sick of getting into trouble, she decides to leave home, ‘wearing my favourite pink silk dress with purple flowers and carrying my wooden school case with something to eat and drink and a change of clothes inside’. When she gets halfway down the hill, her mother catches up with her and takes her home.

Tristine Rainer, an American scholar and teacher of autobiography, defines New Autobiography as finding the story of the hidden meaning in events and characters, interpreting one’s life as a dream. McGee-Sippel often achieves this dreamlike quality in her writing. But I longed for more pauses in the narrative to allow space for dramatic and mysterious scenes of vivid detail, such as the stunning scene when, accompanied by her husband, Lorraine enters the nursery at Scarba where, as a baby, she had waited for adoption. Now she imagines herself reaching down into a bassinet and cradling her infant self, with the unspoken words: ‘You are safe now, darling. You are loved and wanted. I am taking you home with me and Kevin.’

Comments powered by CComment