- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Reviews

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Use-by date

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A popular myth holds that all librarians are inspired by a love of books. As with all such stereotypes, it doesn’t take long working in the profession to realise that it is only partly true, only slightly more so than the cardigan, bun and glasses with which we are usually endowed in the popular imagination. Librarians, in fact, whatever their initial sentiments about books, commonly become blasé about the volumes they are responsible for and can be pitiless in weeding out the less attractive, useful and popular books from their collections. David Pearson’s new book sets out to make librarians and others who have books in their care think again about their value as cultural artefacts and pieces of historical evidence, especially at this moment in history when they are beginning to lose their primary role as repositories of the world’s knowledge.

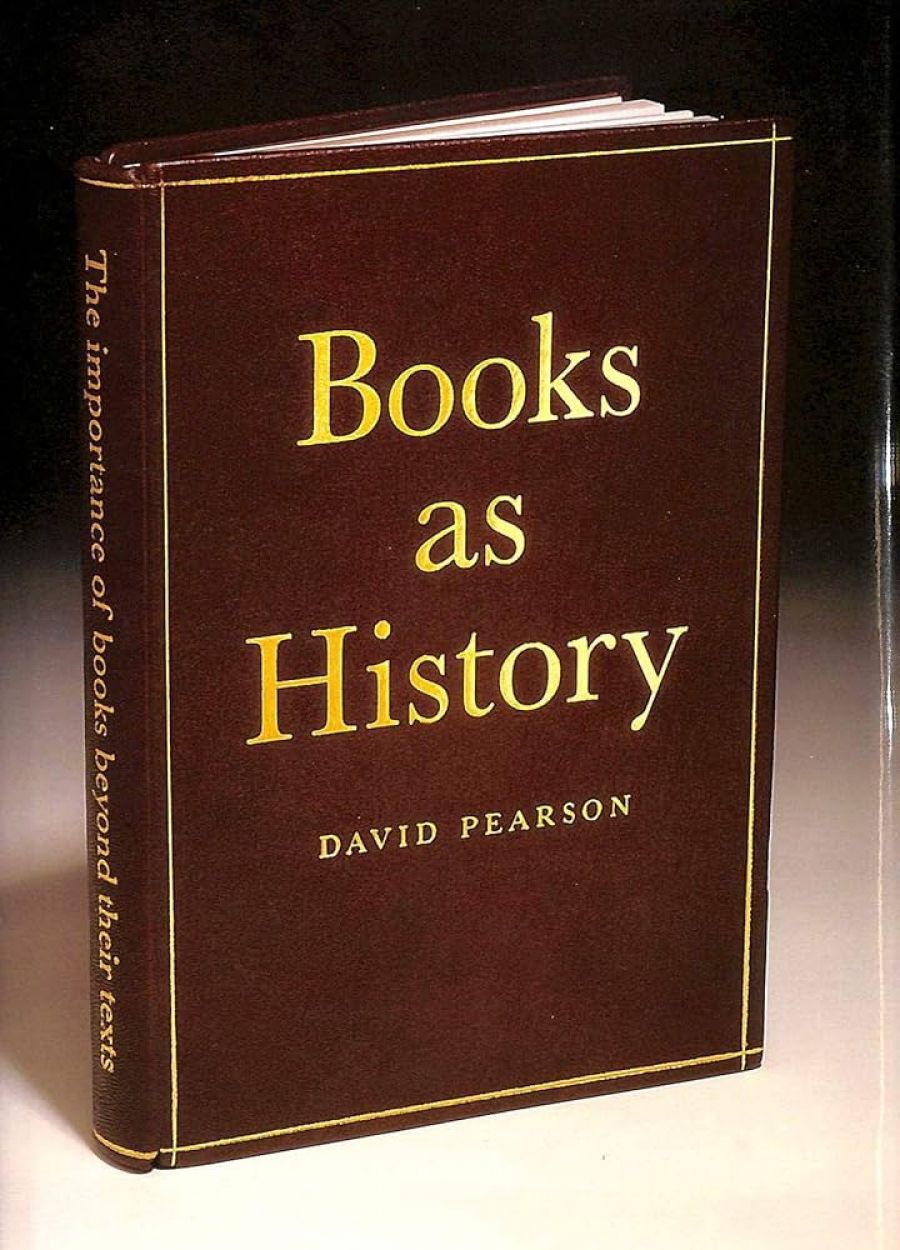

- Book 1 Title: Books As History

- Book 1 Subtitle: The importance of books beyond their texts

- Book 1 Biblio: British Library and Oak Knoll Press, $64.95 hb, 208 pp

The title is, perhaps deliberately, ambiguous: ‘“Books as history” may seem to be a phrase with sinister overtones but let us increasingly recognise that books may be history in an entirely positive sense, as unique objects in our inheritance from the past, with a wealth of meaning worth preserving and interpreting.’ Pearson’s argument is that if we value books only for the texts they contain, ‘their obsolescence seems guaranteed’, but that books have much more to offer. He does not accept the sentimental argument that nobody curls up in bed with a computer – actually, they do. The book has been a wonderful technology, but though ‘we are still waiting for the e-book, with its e-paper, which is genuinely as convenient to read as the paperback we read on our lap, on the train, or in the bath … once the really successful model comes along – which it surely will? – a step change will take place in the transformation process.’ And that’s fine by him:

It is easy to foresee a future in which books have ceased to be the primary medium for transmitting ideas and information; in some cases that time is already here. To take a negative view of these developments is not only ostrich-like but also quite wrong-headed in failing to grasp the opportunities and benefits which electronic communication can bring.

Already, as he points out, scientists are relying on global electronic research networks and ‘humanities scholars are gradually catching up with their scientific colleagues’. Most one-off books are still printed, bound and distributed in hard copy, but government documents, research reports and scholarly journals are increasingly only available electronically. I myself, as editor of an online journal, appreciate the vast benefits of electronic technology: the ability to expand or contract an edition to encompass whatever worthwhile contributions might be on offer; the ease of global distribution; and not least the freedom from the necessity to find money to pay for printing hundreds of copies, some of which will sit dustily in a storeroom until they are pulped when space is needed for something else.

So Books as History is a celebration of the book as a physical item. To describe the books Pearson is interested in as ‘rare’ is beside the point. Collectors of antiquarian books are – or have been – often very concerned with the aesthetics of bindings and the pristine condition of their books. In English Bookbinding Styles, he had gone against the usual trend of studies of historical book bindings and shown as much interest in ordinary, cheap and even temporary bindings as in the deluxe variety. For Pearson, every book of a certain age is rare because every book, before the Industrial Revolution swallowed up the printing and binding trades in the nineteenth century, was a handmade object. Books were not bound by publishers but sold in sheets, and binding was organised either by booksellers or the eventual purchasers, who would commission local binders to make up their books cheaply or luxuriously, as their means dictated: sometimes in inexpensive soft covers of vellum, or, at the other end of the spectrum, in lavish gold-tooled, leather-covered boards embossed with the family coat of arms.

The uniqueness of books, for Pearson, derives from their history after production. The usefulness of holding examples of different editions of a book is generally accepted in the library profession, but librarians will usually demur at adding a ‘duplicate’ copy of a single edition of a book to their collections. However, a typical used book can contain many types of unique evidence, from an owner’s name on the flyleaf or bookplate on the front paste-down, to marginal annotations and family records of births, deaths and marriages on the blank pages.

How much does this matter? Much depends on what traces of individual history each copy retains. Books have influenced people, and shaped as well as reflected their interests. The mere fact of recorded ownership in a particular book at a particular time can tell us something about both owner and text; it can allow us to make deductions about the tastes, intellectual abilities or financial means of the owner, and it can illustrate the reception of the text at different periods in history. If the book is annotated, we can see further into that world of the private relationship between reader and text, and the impact of books in their contemporary contexts.

Books owned and annotated by famous people have always been valued. Pearson would like us to be more democratic in our attitudes and to treasure all the messages books convey from the past, whether they issue from the pens of the great and good or from the more lowly and anonymous classes.

Like many professionals of our times, Pearson regrets the rash actions of our predecessors:

Discarding original bindings, replacing endleaves, removing fragments, washing away or cropping off inscriptions and marginal notes are all processes which have been carried out with ruthless efficiency (and the best of intentions) by previous generations of library custodians, whose primary concern has been to keep the books in a fit state to be read.

Perhaps with the coming of electronic surrogates, library books may be allowed to retain more of their history. The challenge will be to make sure they continue to be preserved at all once their original primary role has been superseded by electronic substitutes.

In Australia, at least, we are not likely to discard lightly any book published before about 1800. They are uncommon and valued objects, and are mostly in the hands either of discriminating private collectors or of special rare book custodians. The challenge comes with more recent books. There is a limit to space and despite the onset of the electronic age, more and more books are being published. Even modern books can contain annotations which make them unique objects, but they can’t all be kept, as Pearson acknowledges. As a library manager, he understands the difficulties of limited space and resources that public (and many private) institutions face. We all know the irritation of encountering a previous reader’s fatuous commentary in a library book. If we treasure the annotations of the past, why should the scribblings of our contemporaries be despised?

Fittingly for a book about ‘the importance of books beyond their texts’, most of its 208 pages are illustrated and many – possibly more than half – carry no text apart from captions: it is not unusual to have to leaf through three or four pages to find the continuation of the text. Every illustration has a point: this is no decorative coffee-table book. Nevertheless, it is a beautiful object in itself, well designed and printed to the highest modern standards. Pearson concludes his argument by urging his readers to ‘write your thoughts in the margins of this copy – if it is yours to write in – and turn it into a unique object for posterity’. Despite Pearson’s exhortation, I won’t be able to bring myself to deface this lovely book with my malformed scribble.

Comments powered by CComment