- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘They threaten and they bless’

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When Petrus Borel led Victor Hugo’s private ‘claque’ into the theatre of the Comédie-Française in 1830 for the opening performance of Hugo’s play Hernani, he and the others of the Romantic ‘push’ fully intended their actions to precipitate the death of classicism in French theatre. They succeeded. Had Peter Porter been in the audience, one wonders where he would have positioned himself between the Romantic shock troops (in part driven by the compulsions of the Petit Cénacle) and the classicist critics who panned the play and all it stood for in the press the next day. The performance and the attendant conflicts became known as ‘La Bataille D’Hernani’.

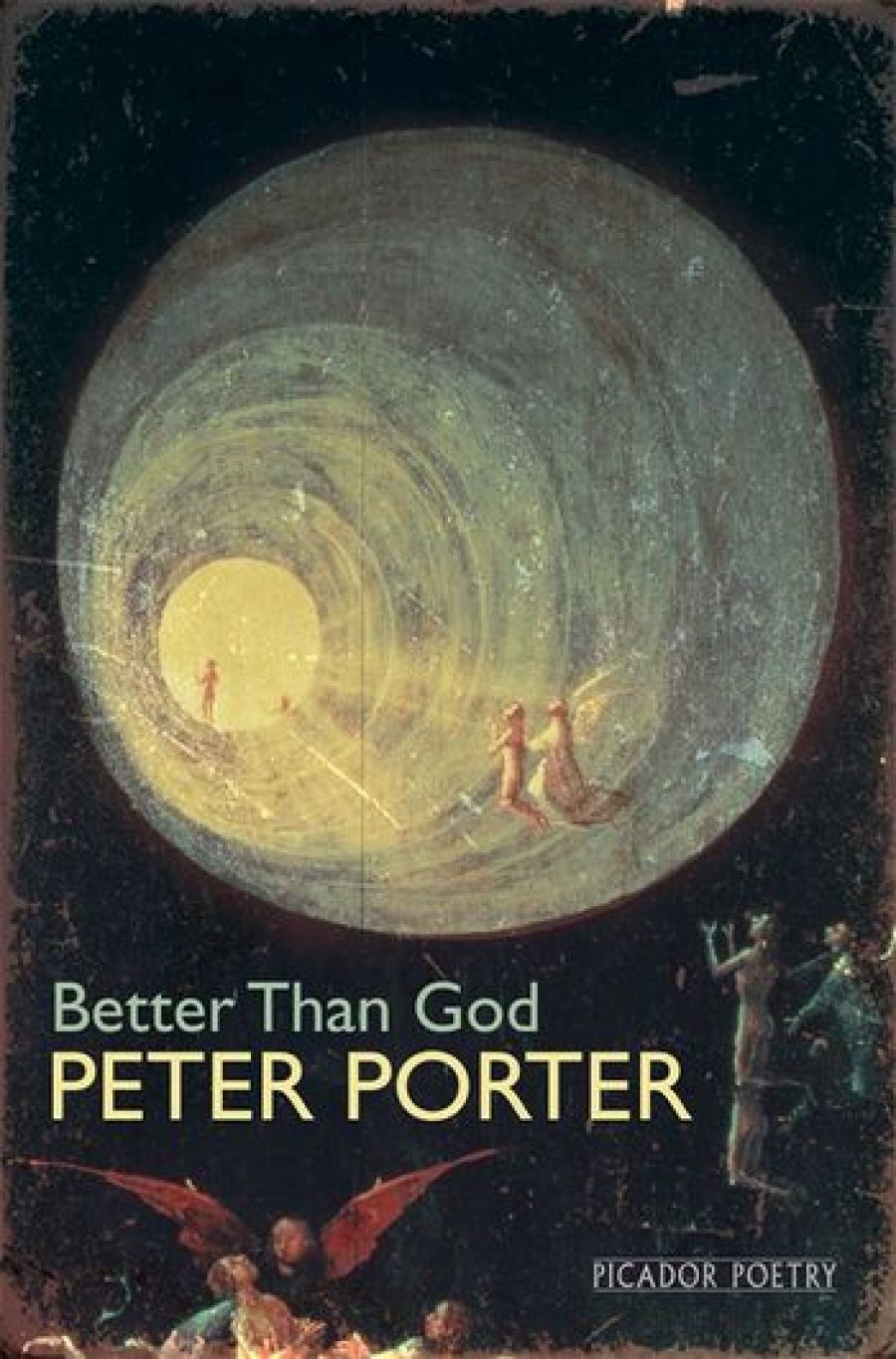

- Book 1 Title: Better Than God

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $29.99 pb, 154 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Porter’s own poetic inheritance, traceable from Homer through Horace to Dryden and Pope, is more about prosody than sensibility. This might seem like heresy to those who know Porter’s remarkable oeuvre well, but I am sure all would agree it shows great diversity in thematics and, ultimately, position of voice. Porter’s voice, although considered to express a social criticism in which the foibles and false values of society’s ‘veneer’ are scrutinised against the question of what constitutes the self – what is left for the individual in the societal ‘melting pot’ – is actually far more mobile and paradoxical than has been widely accredited. The position of a unified self is constantly under scrutiny in this new book: in ‘The Violin’s Obstinacy’, the displacement of self through the object (violin) is a resonant irony (I am reminded of Megadeth’s astonishing ‘Hello me ... It’s me again’).

In his landmark study of Porter’s poetry, Spirit in Exile: Peter Porter and His Poetry (1991), Bruce Bennett effectively locates the core themes and concerns of Porter’s working life through to the beginning of the 1990s. In drawing an allegorical relationship between life and the political, social, aesthetic and theological concerns of the poetry, Bennett homes in on the element of loss that drives the voice (I would argue ‘voices’). From Bennett’s introduction, I will cite two points that I think are of immense relevance to Porter’s new volume, Better Than God, whose publication coincided with his eightieth birthday in February 2009. Bennett writes:

Since allegory has been observed to arise chiefly in periods of loss, when a ‘powerful theological, political or familial authority is threatened with effacement’, the story of Peter Porter might be linked with two major losses of the post-second world war years in western industrialised countries: the loss of a sense of the past, and the loss of religious faith.

Bennett’s observation remains true in respect of Better Than God, and one could make other points (as Bennett does elsewhere) regarding personal loss and the loss of aesthetics through society’s materialism; but I feel that the new work might well bring about an entire reframing of these allegorical ‘losses’. In Better Than God, Porter has established a definitive form of poetic ‘negative theology’ in which an apophatic poetics is counterpointed through the formal prosody, the defined verse forms that offer a mathematical certainty of order. Defining ‘God’ through what is not said, or what cannot be said about the state of perfection, somewhat begs the question in poems so full of discussion about ‘God’. But are the poems actually speaking of God, or are they speaking of a Western history of creating God/s? I would argue the latter, and will return to this issue shortly.

The second point from Bennett’s introduction that I wish to take as point of departure is the notion of Porter as a ‘sceptical humanist, who bears the traces of a near-religious nostalgia for a barely apprehended but haunting notion of perfection, presented most often as gardens which are reclamations of an Eden’.

This is certainly a sound observation, and remains true as we read Porter’s abundant work published since the appearance of Spirit in Exile. However, with this new volume, we might question the idea. Porter has never been a binary thinker, though his use of heroic couplets and aphorisms, and his underlying wit and irony, might lead the casual reader to assume that he is.

One should be wary, though. Porter’s juxtapositions are never simple comparisons limited to the sound bites of form, but often shift through a whole poem and indeed a whole book. A Porter poem is often a complex amalgam of associations, comparisons and seeming contradictions. The key lies in paradox. The garden and the room, finite spaces that are organised (or allowed to run riot), are locatable fixed values through which Porter measures the presence and absence of God; what can and can’t be talked about. The room may be the place where you are alone with your thoughts – a Hell or even, possibly, an earthly paradise, often both rolled into one – and the garden a place where humanity and nature can approach something verging on harmony. Porter’s gardens have always been about the prospect of Fall and rejection, and in Better Than God that prospect has become a reality. This is a postlapsarian world, as all Porter’s created worlds are, but the voices shift closer to non-participation than ever before. Porter has always been the critical observer, but his poems wrestle with age and death; there is something else at work.

A key poem in the new book is ‘Voltaire’s Allotment’. As Candide left an Eden and ended with the notion of cultivating his garden, Porter infiltrates the satire to make his own satire of the urges of self and community. In damning the vileness of the physical world and throwing his lot in with the garden of ideas, the poet in essence critiques his lifelong use of the garden as an Edenic symbol (love and sex thrive in Porter’s gardens, but there is often the shadow of Fall and death). Voltaire is at the core of pre-revolutionary French classicism, and in many ways symbolises what the Romantics on the verge of the July Revolution of 1830 were resisting. I would argue that Porter is resisting his own bent toward classicism in this poem and many others in the book. Why is this? Because aesthetics and politics are unresolvable and even poetry, which Porter still celebrates as a form of triumphal deliverance against the odds, must deal with a list of horrors that doesn’t lessen with knowledge and experience but simply grows longer. Allegory parodies itself.

In ‘Voltaire’s Allotment’, a poem in the ‘voice’ of Voltaire as both historical figure and banner-waver of classicism, the poet dissects the role of the poetaster and critic, the utilitarianism of making a living from the arts, and from philosophy. Porter calls cities vile, yet most of his oeuvre is inspired by cities and towns; he positions the small, personal, productive vegetable patch, the allotment, as the garden – not a place of pleasure but of work; he makes complicit the role of the Western poet perpetuating the list of horrors. It is double irony all the way – Voltaire’s, Porter’s, the issue of the self. Candide, in which we are told ‘Il faut cultiver notre jardin’, is allegory. Porter’s poem is allegory. This ironising of Voltaire’s ‘allotted’ legacy is further evidence of Porter’s unwillingness to be locked into a classicist camp. On its own, classicism can lead to façadism; it needs to be ‘used’ in conjunction with a version of Romantic subjectivity, and a public conscience and responsibility.

In many ways, Porter’s reconfiguring of the garden is as much about the counterpane of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Child’s Garden of Verses as it is about Voltaire, or even Genesis. The infiltration of the gardens of the ‘ancient’ world by the machinery of new empire is captured in ‘Birds in the Garden of the Cairo Marriott’, where Porter’s often metempsychotic creatures, birds (especially sparrows, sometimes elsewhere pursued by cats), act as go-betweens of the capitalist hotel chain’s garden and the ontological space of the spiritual garden:

and your big rivals, we’d call them crows

but they are dignity itself in brown tuxedos,

peering from high perches of a Disney Ramasseum,

speaking faultless American forever,

they must be Prefects of the Underworld!

Porter’s use of mythologies is often allegorical and always immediate. Mythology is a template, a mnemonic, and inevitably a truth as relevant (and dangerous) as the Hadron Collider. It is not a quaint usage of the past but a challenge to the empirical (and always challengeable) data of history. Renowned as a poet and critic of vast reading and knowledge, and, as Bennett notes, one who enjoys making good use of this in conversation, Porter is nonetheless uncertain and unsure of the value of knowledge.

To digress: in ‘Vita Somnium Breve’, a magnificent elegy for the Cambridge poet Veronica Forrest-Thomson, Porter reflects on the isolation of knowledge, on the failure of both traditional and innovative poetics to create a bridge of empathy that would draw a poet of language out of that dark place. Language at once liberates and isolates. That is the paradox at the root of Porter’s poetry, especially his masterwork, The Cost of Seriousness (1978), which reflects on his first wife’s death as well as on the rejuvenating nature of new love (also discovered in a garden). This seemingly irreconcilable equation is at the core of Porter’s poetics. Ironically, for a poet with such apparently clear-cut satires, the equation is never straightforward.

In a superb, understated poem, ‘Young Mothers in the Square’, Porter creates a form of ars poetica in thematics, a reflection over his decades of writing the garden in the city. The city is much like the enclosure that John Clare so bitterly resisted: the private spaces consumed by the corporate, and the corporation of the city itself, profiting from the public. Porter changes what the city can mean, making it an urban and a country space in one – through its gardens, but also in the way different components of the larger entity relate and communicate among themselves. In this poem, the persona reflects on taking children to such gardens.

This has emphatic impact if we take into account Porter raising his two daughters alone after the death of his wife in 1974, and the isolation of the parent who is defined by love of his children. The question becomes a personal one, but also part of the broader ontology of how God loves in a world that will take what is most beautiful, even pure. Does God damage because God is pure and can’t be rivalled? This is a twist to a poetic negative theology. The poem begins with a question:

How long is it since I, as them,

An old rose on a branching stem,

Kept watch through cloudy grass and sun

That no harm come to anyone

In this Our Pale, yet might deplore

The garden as a metaphor

Where married love dies intestate

En route to some half-hopeful date.

The personal biography is clear, but so is the questioning of a broader poetics of allegory. Porter has visibly absorbed critical responses to this work, including Bennett’s. He has a sharp and generous critical mind. Better Than God includes a poem of dialogue between Stravinsky and Money; many of the other poems in this book work as dialogues too, with Porter’s earlier poetry and the critical questions and positions they have evoked. Loss is irreconcilable for Porter; he doesn’t get over it, and why should he? That doesn’t mean he closes off. Rather, he opens new threads of survival and love. His children, and the symbol of innocence, have remained steadily liberating for him. I would argue that they are a theology rather than a religion. Indeed, I would argue that they are ‘Better Than God’ because they don’t need to define God to believe (or not). They are more than metaphor – metaphor is what affirms God without evidence. Poets are just halfway-there scientists. The poem ‘Young Mothers in the Square’ shifts into the irony of parenthood and the acquisitive aspirations of the adult world, of ‘society’. But such darkenings of the pure palette are challenged by the poet himself: ‘A shadow falls across the lawn; / Is it the poet’s unearned scorn?’ This is ‘answered’ by yet another question: ‘How can they play, as Gray observed, / Unconscious of their fate?’

Fate is the linchpin for Porter. ‘As flies to wanton boys are we to th’ gods/ they kill us for their sport’ comes from Shakespeare via Thomas Hardy for Porter. It is unsurprising that Porter once edited an edition of Hardy’s poems; interestingly, it was an edition of landscape poems. In his gardens, Porter paints Hardy-like landscapes; Wessexes in London, almost. (His Australian gardens, which we will consider shortly, are something else again.)

‘Young Mothers in the Square’ finishes uneasily. It laments fate and a brutal or at best indifferent ‘God’, but also the inevitability that children ultimately become part of a desensitised, materialistic world.

Better Than God has a Möbius-strip view of the colonial. Poems that take us back to the poet’s childhood in Brisbane present us with interior and exterior views resolving in a cultural/physical dichotomy. We see what compelled the poet to leave Australia for London in the early 1950s. Though Porter didn’t return to Australia for more than twenty years, there has been an industry in rehabilitating him to the national canon since then. True, his frequent visits meant an increase in Australian references in Porter’s work, and he has often been left as positioned neither in Britain nor in Australia (this is seen as poetically vital in terms of Porter’s unique way of seeing place and origins), but ultimately the question of exclusion and inclusion has been more about an issue of nationalistic gatekeeping than anything else.

Porter doesn’t need to prove his connection to Australia to be significant to poets and readers here. The issues he deals with, inflected through his life’s experience, and testing language within formal frameworks (I would argue that he is one of the most technically innovative poets because of this), are translations, allegories and interpretations of the world’s texts. ‘The Burning Fiery Furnace’, a poem deeply resonant on a literal level in a country that has burnt so much and will burn again, puts canonical literary hunger into perspective. The ironic beginning is also a reflection on an interiority that is vulnerable in so many ways:

Born to a seamless ordinance of heat,

Small wonder I best remember Indoors,

The too-small carpets slipping round the floors

And ‘Under the House’, a region to retreat ...

Australia as an outdoor place, as opposed to the rooms in which the poet writes in London (or hotels elsewhere), is confirmed in the capitalising of ‘Indoors’. A child who spends too much time indoors in Australia, as Porter seems to recall, is considered un-Australian. The Outdoors is painted as natural and safe, Indoors as unhealthy physically, socially and mentally. It is a question of the onanistic self versus the healthy communal self. The ‘Je’ of the garden is one of individual retreat rather than community-minded looking to home. Sadly, as we know, neither inside nor outside is safe in a land that is burning. This is a portrait of a personal ‘enfer’. The colonising desire for control, the desire to prosper, is scrutinised, and it casts the expatriate move back to ‘origins’ as a form of decolonising:

I write this down I’m sure because I’m old;

The country of my birth’s become hot news

And selfishness should always take short views –

My ancestors came out and found no gold.

Written before the latest fires in Victoria, this still reflects on a land governed by fire. And in terms of the poet’s ancestors, we read in ‘How the Eureka Stockade Led to Boggo Road Gaol’ of a complicity in the colonisation stakes that is remorseless in the telling and condemnation. According to the poem, Porter’s great-grandfather, ‘Robert Porter, England’s son’, an architect, built the famous gaol. If the Eureka Stockade was a point of colonial crisis, Porter’s ancestor is shown profiting from and enforcing the status quo, entrenching the punitive as a kind of extension of the convict era (the gaol was built after transportation had finished). In his uncompromising assault on the hypocrisy of the debate of nation, Porter moves to finish this narrative poem in its neat five-line, two-rhymed stanzas:

It’s all gone now – gaol, stockade,

The Porters cut to stem.

A moral, is there one? Invade!

Australians know their land was made

By history for them.

Bruce Bennett once argued that Peter Porter was a socialist who accepted market capitalism. I profoundly disagree – now and then. I think Porter, at least in his poems, is a trenchant left-wing commentator whose politics are unforgiving.

Porter does not accept anything at all outside the functionality of poetry as a medium of communication. He doesn’t accept ageing, and he doesn’t accept death. Talking about it doesn’t mean you are hiding from it, or wanting it. The issue of ageing in this work is not one of chronology, or even the self, as much as the way in which discourse forces the discussion. We celebrate Porter at eighty, but in a sense age and history are irrelevant. In poems that go back to childhood, that reflect on forebears killed during World War I (including an uncle Porter never knew and who died away from ‘home’), we confront the reality that home is not as fixed as we imagine it. Whom we die among is paradoxically arbitrary and yet defining. In ‘Christmas Day, 1917’, the cemetery is the garden in which the living and the dead converse according to the rules, the prosody:

How extraordinarily neat, well-spaced,

The Prowse Point Military Cemetery is –

How mistaken my memory of my family’s memory

Of these our far-off dead.

Two weren’t even born where I thought they were,

My Mother must have been living still at home

When the news came, but she didn’t die alone.

My civilian Father did.

In this remarkable book of relatively short poems, Porter journeys past his poetry’s motifs: the garden, death, theology, aesthetics, consumerism, the philistine, love, loss, the nature of Hell. His poems are segmentary in the sense that you can extract part that works intact as aphorism, but as a whole they add up to so much more than the sum of their parts. The poems progress in a linear fashion and yet ripple with cross-talk and contradictions. They are logical and irreverent at once. Science is wrestled with as a system of logic, but its participation in Western profit-making and consumerism is offset against its benefits for humanity, and language itself is scrutinised, its ability to ‘parse’ the reality we live, and the claims and hopes of art-for-art’s sake, left wanting.

Porter is also a poet of great lyric beauty when he wants to be, and is impressively able to embed this in social (or religious) satire. The satirist is always part of what he or she satirises, and Porter relishes participation, yet there is something transcendent as well that prevents the critic from terming his work ‘just’ satire or a play between society and self. Take these remarkable concluding lines of ‘By Whose Permission Do These Angels Serve?’: ‘ ... Easy to imagine angels / as flamingos wading in a lake, and quite like God, / being neighbourly and pink each day at dawn.’

Although Porter’s religious and theological beliefs are secondary to an understanding of his poetry, I felt that a book so concerned with a public God and a private God begged the question. When I asked Porter a few questions about his beliefs, he replied as follows:

God is so far the hinge word of our every attempt at formulating a response to the unanswerable mystery of life that asking whether you believe in Him/Her/Them is almost an exercise in schoolday debating. In short, God is an existential set of coordinates.

Theology is more interesting than Philosophy, but it is also highly technical and, while I respect its complexities, I’m not closely concerned with it. I am not concerned greatly either with the Dawkins debate, though, since we all should honestly declare our loyalties, then I would describe myself as an agnostic. In my braver moments, I would say I was angry at God’s being used as a force of censorship and entrapment. Look at the three-line title poem of my book. It points out that if God set everything up it’s been left to us to work his universe and like score-readers we are good at it – i.e. ‘better’ than him. With the added inference that nobody can know ‘Him’ without us.

I notice that my atheist composer friends like to set to music only sacred texts. The reason? Authority. God and his religious history give us a good half of our subject matter. Perhaps we are exploiting Him.

Poetry concerns itself with love and fear of living and dying and is both emotional and factual. I tend to feel that modern poetry collapses into egoism and anecdotalism – its ecstatic moments seem hollow without a reference system to things beyond themselves. Maybe God has just gone away for a while – Deus absconditus. But it’s hard to believe in Heaven, Hell and eternal life. The one good thing about dying might well be that it does away with death.

Porter’s poetry is definitively based in a reference system, as I hope to have shown, but I feel that Porter’s wariness of egotism extends back further than modernism into the very classical roots he draws on. Religion supplies a template for Porter’s critiques, as much as it is a target. His concern is with false routes to God.

In a modern, ‘Godless’ and brutal world – a world in which, as we read in the final poem of the book, ‘River Quatrains’, ‘Our City Fathers’ planning is polite. / The abattoir is on the edge of town’ – there is aesthetic as well as spiritual salvation:

I’m on a river bank. I think I see

The farther side: a choice of nothingness

Or Paradise. My poems wait for me,

They look away, they threaten and they bless.

Of course, the salvation might not be where we have been told it should be. The poet needs to create the possibility even within the most damning poems of social scrutiny. For me, and for many poets of my generation, Peter Porter has led to an investigation of what this nothingness might constitute, spiritually and aesthetically. The Paradises on offer have been overwhelmingly inadequate. For many of us, he has been a classicist fully aware and understanding of the Romantic urge, and necessarily making something new out of the collision between the different modes. For Porter’s readers, all of his trademarks and more are in this wonderful new volume – a late flowering, some might say, but all the more gritty and resolute, I’d suggest. Porter has never stopped increasing. His verbal play, his punning, his incisive use of epigram and paraphrase, chiasmus (Porter’s poetry is a lesson in classical rhetoric fused with an ongoing crisis of ‘modernism’ and modernity that makes his poetics essentially radical), and an ekphrasis that extends into music and poetry as well as art, are second to none. Porter’s references to poets, artists, thinkers, scientists, musicians, and other cultural and historic figures are both comparative and emphatic, but also participatory: he speaks with the dead as much as the living; they share with him and give comfort and distress in equal measure.

The tyrannies of political state and organised religion also give certainties that might seem addictive and desirable, but Porter knows all good order comes at a price: ‘They call it valency when we discuss / How murderous this numbered regimen’ (‘Strontium to Mendeleyev’). Whether it is the periodic table, or scientists at the Collider, a mysticism is never far from the facts, and Porter homes in on that with exacting precision. But in the end – and ends are certain, even these of the conversation of family, of friends, of strangers – every Paradise must fall, and one is confronted with the fact that these gardens are very often trapped by the will and purpose that made them.

A particularly sad, elegiac poem, ‘Ranunculus Which My Father Called a Poppy’, tracks a guilt and disappointment which underpin, in their different forms, all our attempts to create Edens. In this way, Porter’s poetic lineage owes as much to the failed Edens of Christopher Brennan as it does to the gardens of Alexander Pope’s poetry, or the terraces and gardens that helped feed and pleasure ancient Rome. They serve neither those who attend nor those who stand and wait ...

Not for him the red of Flanders Fields sprung from

his Brother’s body steeped in duckboard marl

nor the necrology of the Somme.

Defeat lived in those several petal folds,

that furry stalk and leaf, those half-drenched pinks

and shabby-borrowed golds.

Comments powered by CComment