- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Miller’s own crucibles

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If you felt there was a touch of hubris in Baz Luhrmann’s naming his movie Australia, you may think the opening sentence of Christopher Bigsby’s biography of Arthur Miller even more startling in its pretensions: ‘This is the story of a writer, but it is also the story of America.’ Not, observe, ‘a story’, but ‘the story’. This grandiose proposition helps to account for nearly 700 dense, uncompromising pages – and they only take in the first half of Miller’s long life (1915–2005).

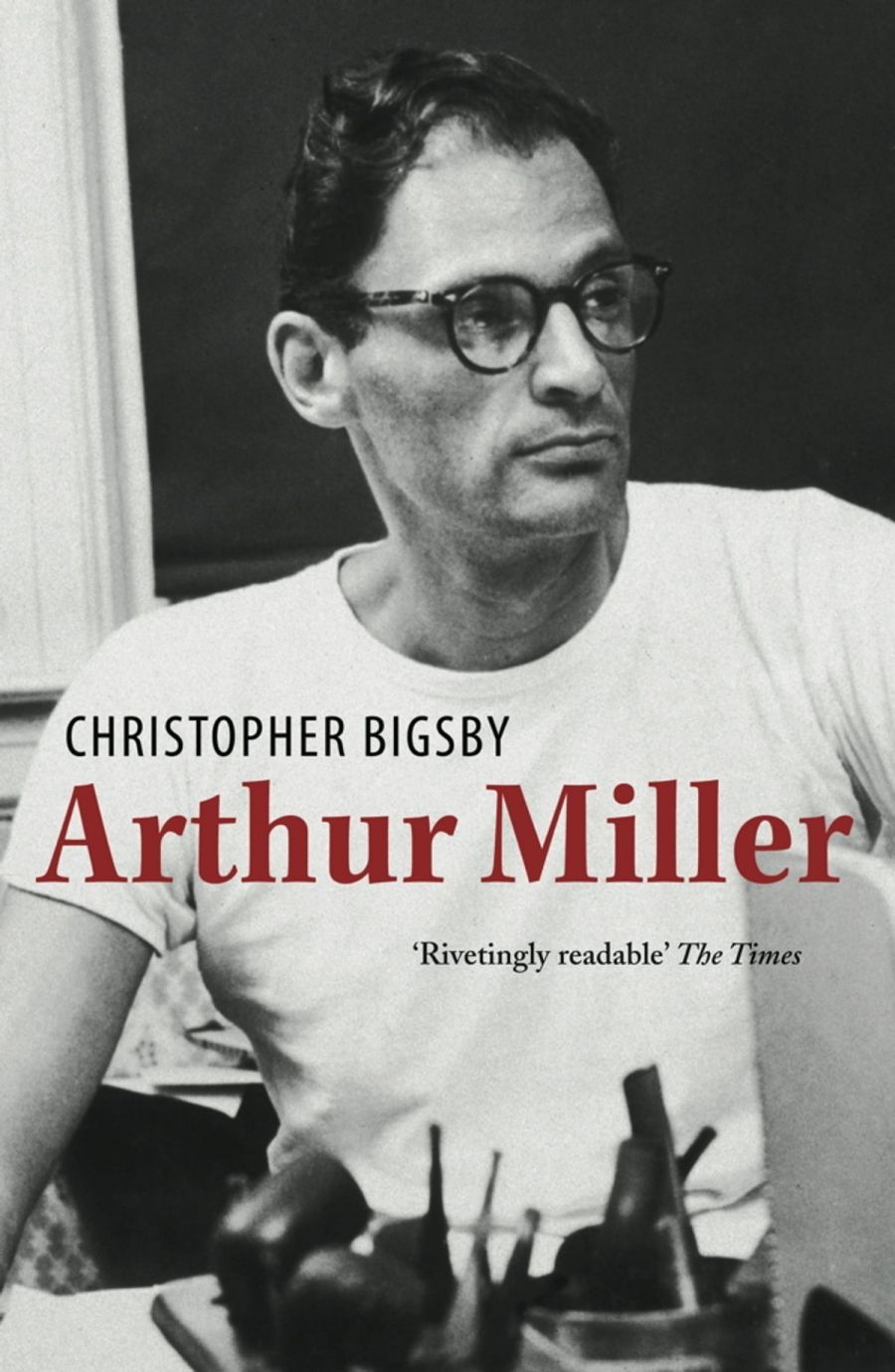

- Book 1 Title: Arthur Miller

- Book 1 Biblio: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, $75 hb, 739 pp

The Jewish roots are traced to Poland and the westward diaspora that brought Miller’s father to America as an abandoned child who would, like so many, scrabble his way to affluence in the face of illiteracy, and would then, during the Depression, be reduced again to near-destitution. The genesis of Death of a Salesman’s Willy Loman can be seen in the father–salesman’s failure, though the cultivated mother, embittered by the failure, is at a remove from Linda Loman. The father–son relationship, never easy, will surface elsewhere in Miller’s work, and there is a poignantly complex echo of this in the porch Miller built on their East 3rd Street house, and which he attributes to the failed Willy in his most famous play.

Miller never repudiated his Jewishness (though he married ‘out’ three times), but he would spend several decades having to deny his membership of the Communist Party while not repudiating his Marxist affiliations. At the University of Michigan, away from family for the first time, he experienced both literary and political awakening. If Ibsen inducted him into socially committed drama, the Spanish Civil War, the ‘central political and moral cause’ of the decade, made political non-alignment an impossibility for Miller; and ‘support for Spain was also the quickest way to earn an FBI file’. He would be of interest to the FBI for the rest of his life. Bigsby picks his way conscientiously through the tangle of left-wing organisations with which Miller was, or was alleged to be, associated over the decades.

The growth of his sense of commitment to working-class solidarity, and of his general left-leaning, helped to account for his first marriage, to Mary Slattery, daughter of an Ohio Catholic family that welcomed the marriage no more than Miller’s parents did. Bigsby traces the course of this unpromising relationship, believing that Miller did not love Mary but was drawn to her chiefly by shared socio-political sympathies. There are elements of this marriage in various stories and plays, a surprising number of them still unpublished. In an early play, They Too Arise (1937), Bigsby perceives a ‘blend of humour and social drama’. The ‘social drama’ aptly describes most of Miller’s oeuvre, but ‘humour’? On neither page nor stage has he ever suggested the slightest bent for comedy – nor, I might add after Bigsby’s 700 pages, in life.

After his share of rejections, in the late 1940s and early 1950s Miller found success and a distinctive voice in the plays for which he is best known: All My Sons (1947), Death of a Salesman (1949), The Crucible (1953) and A View from the Bridge (1955). Part of Bigsby’s ambition is to offer, as well as a more or less chronological survey of the life, an analysis of Miller’s works. Too often the lives of writers give only a sketchy sense of what the writing was actually like. No one can accuse Bigsby of this; sometimes, indeed, there is almost more analysis than one wants, so that the biographer’s overarching narrative trajectory can be obscured, but the sense of what is going on in the plays, and their connections with what was going on in Miller’s life and in America at large, is solidly there. What is less palpable is how the plays seemed on stage, but this may be because the author was too young to have seen them.

What the plays have in common emerges from these analyses. These are excavations of family tensions, especially of father–son corrosiveness, of the problem ‘of growing rich but trying to think poor’, of the difficult convergence of sexual imperatives and the recognition of what is owed to fidelity, of the overriding interdependence of the personal and the public. It is The Crucible which brings this latter conflict into sharpest focus. Its protagonist John Proctor’s adultery with the seductive Abigail and his subsequent trial, in which he finds ‘I cannot live without my name’, perhaps hews most closely to the facts of Miller’s own conflicts. I don’t mean to sound censorious about the affair that precipitates the end of his first marriage, but he was aware of the potency of sexual demands and, on another level of experience, of the impossibility of naming names when McCarthyism got its claws into him.

The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) was particularly dedicated to accusing celebrities to further its own disgusting activities. Miller, in the light of the ‘negative’ views of capitalist America in All My Sons and Death of a Salesman, and, most glaringly, of the unmistakable analogy at work in The Crucible, was one of its prized quarries over several decades. To his great credit, he – unlike, say, director Elia Kazan – refused to name others whose past had included membership of suspect political groups. In this matter, he sounds essentially admirable, even to the point of suggesting that HUAC already knew the names of anyone he could have named.

There is, disappointingly, almost nothing about the films made from the plays, and Bigsby tends to get the few references to film wrong when they do appear: for instance, Jack Clayton, not Jack Cardiff, directed The Innocents; and Bigsby generalises unwisely when he claims that ‘Hollywood at the time [c.1950] was not overly enthusiastic about significant social issues’. In fact, there was a rash of films explicitly addressing such matters as racial intolerance and the after-effects of war.

This leaves Marilyn. What did she and Miller find – or, at least, look for – in each other? Was it the greatest pairing since black and white? Like so many men, Miller was obviously drawn to her mélange of sexual allure and emotional neediness, and probably felt he was the man to respond to both. As far as she was concerned, Marilyn thought she was moving out of the tinselly corruptions of Hollywood into the ether of higher thought. In the end, neither found enough in the other to answer their needs. Monroe died the year after their marriage (1956–61) finished; his feeling for her feeds into both A View from the Bridge and After the Fall.

What sort of man emerges from Bigsby’s research? One can applaud the refusal to kowtow to America’s legislative measures to bring independent thought into line, or to discredit other people in the interests of one’s personal safety. If the details of how they tried to force him to submit sometimes swamp the man himself, that may be the price the book pays for the thoroughness of Bigsby’s investigations.

Comments powered by CComment