- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘I could give ’em / enough social comment to fill a car park’ proffers the narrator in ‘Busking’, halfway through Tim Thorne’s I Con. In many ways, this book delivers on that promise. Thorne’s targets include war, colonisation, inequality, political deception, capitalism and celebrity. One moment he juxtaposes Dannii Minogue’s career with descriptions of police brutality; the next he bowls a bouncer at former Australian cricket captain Kim Hughes for touring South Africa during the apartheid era.

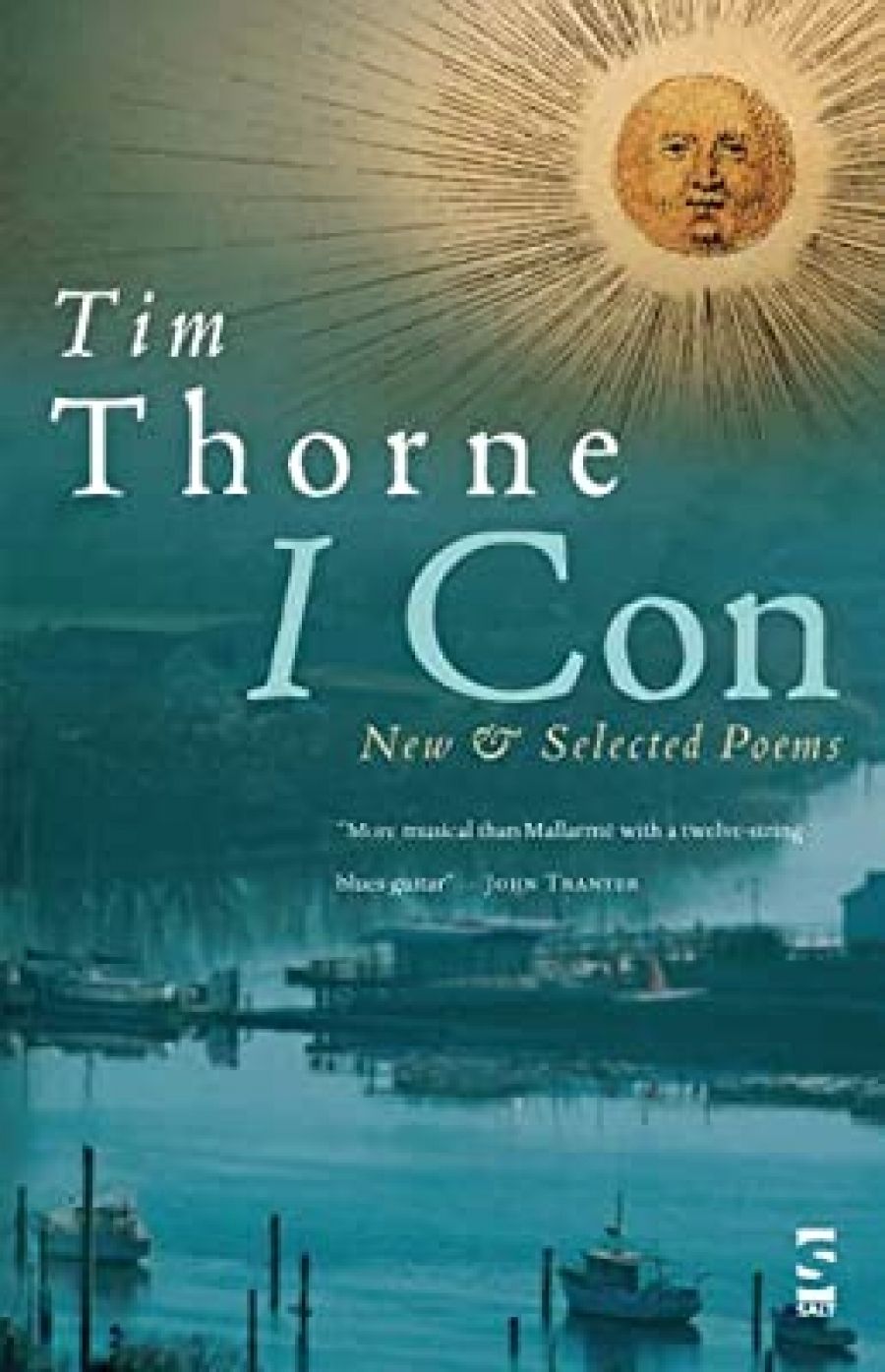

- Book 1 Title: I Con

- Book 1 Subtitle: New and selected poems

- Book 1 Biblio: Salt Publishing, $39.95 hb, 240 pp

Throughout, Thorne shows an empathy with the marginalised and the subversive, and his early poems often shock with their violent protagonists. The young poet is influenced by the protests of Bob Dylan, the cool of the Beats. We can see him hunched over a snooker table while listening to Dylan. He takes aim at Jesus, Kirribilli and the Bank of New South Wales. He pots a few balls.

The pastoral also figures, small-town life captured superbly through the arboreal rhythms of ‘Five Trees’. Further in, selections from The Atlas (1982) map personal and national histories, trace the female body, and chart events in Vietnam in a searing portrayal that fuses the rules of grammar with the language of war. Market jitters satirised in ‘Crash’ with the promise that ‘tomorrow we will read the signs’ are comically prescient today.

Fond of puns and plays on language, Thorne’s poems include ‘There are No Kangaroos in Austria’ and ‘The Bawd, the Lair and Albert Ross’. His first collection was teasingly titled Tense Mood and Voice (1969). The Con of the new title refers variously to the unreliable or subversive narrator, the iconoclastic nature of many of the poems, the cons of history, and the manipulations of generations of politicians, preachers, spin doctors, salesmen and other creatures of ill or mixed repute.

Thorne’s work addresses historical exclusions related to race, class, sovereignty and the excesses of market economies. His is very much a male world. Men with their consciences and their cons, their bravery and bravado, prevail. In the first half of the collection in particular, women appear rarely in the myriad history-based narratives that Thorne has researched so diligently. The unsentimental ‘Elegy for Jenny’ provides a fitting memoir for a lost loved one, but ‘Words for K’ (from The Streets Aren’t for Dreamers, 1995) is the first poem to offer an overtly female perspective. It deals, compassionately, with incest (‘I still sleep on my stomach / in case Satan … / takes me by surprise again / to make me his favourite daughter’), and the issue of sexual abuse is reprised in ‘Elegy for Sandra Dee (1942–2005)’. But while poems such as ‘Naming the Sensation No 2’ speak baldly to the objectification of women, few portraits of robust, independent women emerge. In a book brimming with political subversives of various colours, suffragette purple is hard to find.

Selections from A Letter to Egon Kisch (2007) see the poet drawing on a long line of political satire that includes Pope and Byron and the larrikinism of C.J. Dennis. His octaves extend rhyme to its limits to deliver a tongue-lashing, alternately blistering and comic, if unsubtle:

We’ll never lack for bogeymen or ogres

to frighten us with guns or bombs or rockets.

One wouldn’t need to be as big a rogue as

Saddam or Slobodan to cop the blame,

just have an accent or a funny name.

Thorne’s wit results in some memorably droll lines. On literary cons: ‘someone’s not / the full denko and it might as well be me’ (‘Erechtheus 33’s Apologia’). On the Private Lynch Iraq saga: ‘Jessica, we all pentagonised / over your fate’ (‘Mesopotamian Suite’). While we can cut Thorne some slack given the satirical traditions in which he often works, more of this humour, married with the restraint of irony, might have lightened the shrillness that sometimes characterises his politico-historical narratives.

Many of Thorne’s best poems, as in the elegies, relate to the personal. The intimacy of first-hand knowing and experience give rise to the tender and eloquent ‘Love Poem for Stephanie’ and ‘Mother and Son’. The latter sees love, death and absence melding to achieve great poignancy:

Holding on isn’t always everything. Skin slides.

Too tough to die, too proud to call this living,

you hug into these punctuated hours

our missed half-century of love.

‘For My Father’ also records a loss, but more bitingly, the absent father having ‘conned’ the poet–narrator into being and serving as bitter prototype: ‘When you really died I became / your ghost. Your hairline, chin and gait / returned to haunt …’ For many readers of Tim Thorne, such movingly detailed losses are our great gain.

Comments powered by CComment